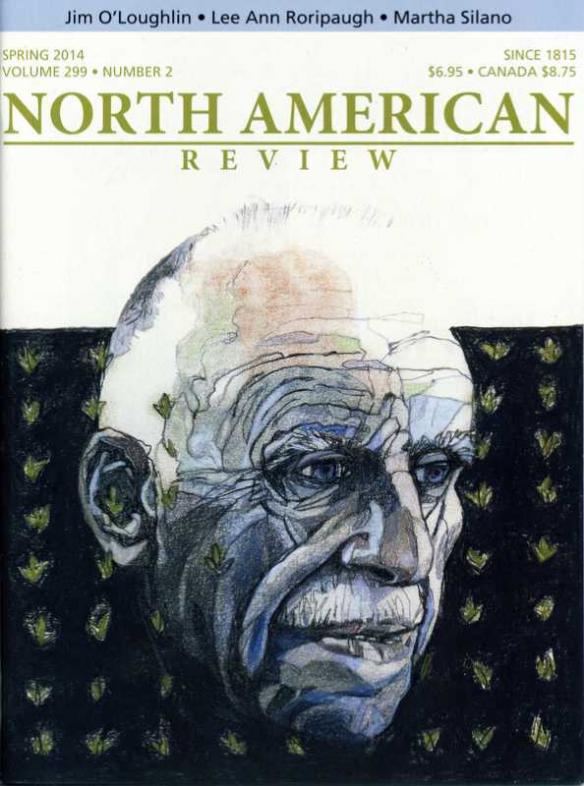

James Hearst’s Constructed Regionalism

My love for the work of James Hearst might simply look like an instance of rooting for the home team. I grew up in Hearst country, Black Hawk County, Iowa. I’ve worked cornfields across the road, now blacktopped, from Maplehurst farm, the locus of many of his best-known poems. I’ve studied with his bibliographers, Robert Ward and Scott Cawelti, and I take advantage of the lovely facilities offered by the James and Meryl Hearst Center for the Arts in Cedar Falls. Jeremy Schraffenberger at the University of Northern Iowa afforded me the opportunity to take a seminar on the work of Hearst and Robert Frost. The local guy, in my opinion, fared none the worse by comparison.

What I most respond to in Hearst’s poetry, however, has little to do with the delights of recognition obtained in the reading of a local writer. I’m inclined to resist perception of Hearst as merely a prairie regionalist, the farmer-poet, the Frost-of-the-Midwest. What I read in Hearst’s poetry is a toughness born in pain, an intellectual audacity, and a humanity, deep and broad, which transcends region.

The region of a poem like “Snake in the Strawberries,” to cite an example, is that of the collective unconscious. This poem, first published in 1943, toward the end of Hearst’s career as a working farmer, seems to have been a particular favorite of the author: it appears, unchanged, in two of his original books of poetry, and he used it to title his most comprehensive volume of selected verse. Just as the persona of farmer-poet was one that Hearst more-or-less consciously adopted (he lived in town for the bulk of his writing life), any notion of farm in “Snake in the Strawberries” is a construct, a strawberry patch of the mind.

Snake in the Strawberries

This lovely girl dressed in lambswool thoughts

dances a tune in the sunshine, a tune like a bright path

leading to that soft cloud curled up like a girl

in her sleep, but she stops at the strawberry bed

carrying nothing but joy in her basket and it falls

to the ground. Oh-h-h-h-h, her red lips round out

berries of sound but the berries under her feet are

not startled though they sway ever so slightly

as life long-striped and winding congeals into

form, driving its red tongue into her breast

forever marking its presence and turning into a shiver

barely a thread of motion in the clusters of green leaves.

She stands now as cold as marble now with the thought

coiled around her, the image of her thought holding her

tightly in its folds for it is part of her now and dimly

like faint sobbing she knows that part of her crawls

forever among green leaves and light grasses, it is the same

shiver that shakes her now and now her hair tumbles slightly

and now she feels disheveled but the spell breaks finally.

For the warm sun has not changed and maybe the tune

of her coming still floats in the air but the path

no longer ends in the cloud. She fills her basket taking

the richest ripe berries for this is what she came to do,

she touches her breast a minute and then the ground

feeling beneath her fingers the coiled muscles

of a cold fear that seems so dark and secret

beside the warm colors of the sunlight

splashing like blood upon the heaped fruit in her basket.

The tone here is not pastoral but mythic, the setting a long-ago, far-away anywhere in which Hearst draws back the curtain on a retelling of the legend of the Fall, one that can be read as doing parodic work upon the original. In its “Oh-h-h-h, her red lips round out / berries of sound” the poem takes on a quality of archness, a cheeky modernism that recalls, to me, the stance of that other sly Iowa regionalist, Grant Wood. This strawberry girl and the prim farm-wife of American Gothic are shown to be performing a naiveté. They know you’re watching.

Hearst’s conversance with the approaches of modernism extends to the poem’s idiom. The language of the startling, slippery sentence that forms the center of “Snake in the Strawberries” doubles back on itself in cubist hiccups, with six iterations of the word now within what the poet would have us conceive as “the image of her thought”:

She stands now as cold as marble now with the thought

coiled around her, the image of her thought holding her

tightly in its folds for it is part of her now and dimly

like faint sobbing she knows that part of her crawls

forever among green leaves and light grasses, it is the same

shiver that shakes her now and now her hair tumbles slightly

and now she feels disheveled but the spell breaks finally.

The breathless, in-the-now quality of the passage mounts in tension, mimicking its own action: read aloud, the concluding dactyl of finally represents a relief, a chance to inhale, a literal break.

The poem’s strangenesses include its mantle of persona. The overt preciousness of the opening image, “This lovely girl dressed in lambswool thoughts” is the set-up for a turn, a deepening of understanding as this cut-out paper doll, this observed girl in a lambswool fairy-story, increasingly stands in for the writer himself. The effect is defamiliarizing, a queering of legend in which femininity and innocence, lambs and berries and light grass, become emblematic of a state of dread, the condition of one to whom something bad is about to happen.

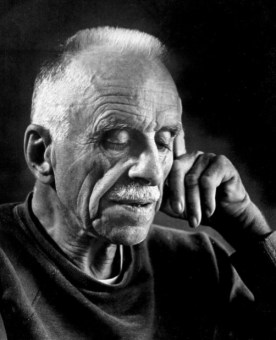

I heard James Hearst read one time, when I was in high school, at some kind of young writer’s event at Northern Iowa. I wish I had a clearer memory of what he read or said that day, but I suspect the thoughts of my sixteen-year-old self were elsewhere. I remember the man, though, rolling himself into the room, looking old and knowing, a leathery old farmer in a wheelchair. He was the age of my grandfather, who had recently suffered a stroke.

It’s tempting, I think, to read disability into Hearst’s work if we know that a defining event of his life occurred at age 19, when he broke his spine while diving into the Cedar River. It seems likely that, were it not for his subsequent paralysis, we wouldn’t know Hearst the poet today. The fact is, though, that Hearst rarely wrote about disability in his poems, and then only obliquely (The prose is a different story: his autobiography, My Shadow Below Me, opens with the accident).

Whether or not we read a “feminized” condition of helplessness and disability into “Snake in the Strawberries,” however, the poem seems certainly to emanate from the perspective of somebody who has confronted disaster, who knows its arbitrary suddenness. The poem happens in a a place of “faint sobbing,” where fear has “forever mark(ed) its presence.”

In historical context, it is just as tempting to read “Snake in the Strawberries” as a wartime poem, of which there are many in Hearst’s body of work. In any case, the proximity to disaster that we read in this and other of Hearst’s poems lends it a portentous note, an alertness to what’s coming.

To read “Snake in the Strawberries” is to experience something like the opposite of pastoral comfort, and the recognition I find there is not one of place, but of the universality of disaster, even amid the warm sunshine and ripe berries of its aftermath. Regardless of the region or setting of his work, Hearst is a poet who won’t let us look away from “a cold fear that seems so dark and secret / beside the warm colors of the sunlight.” It is that probing, open-eyed awareness that keeps me returning to his poetry.

Recommended

The Shirt

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings