Late Night at the Bar

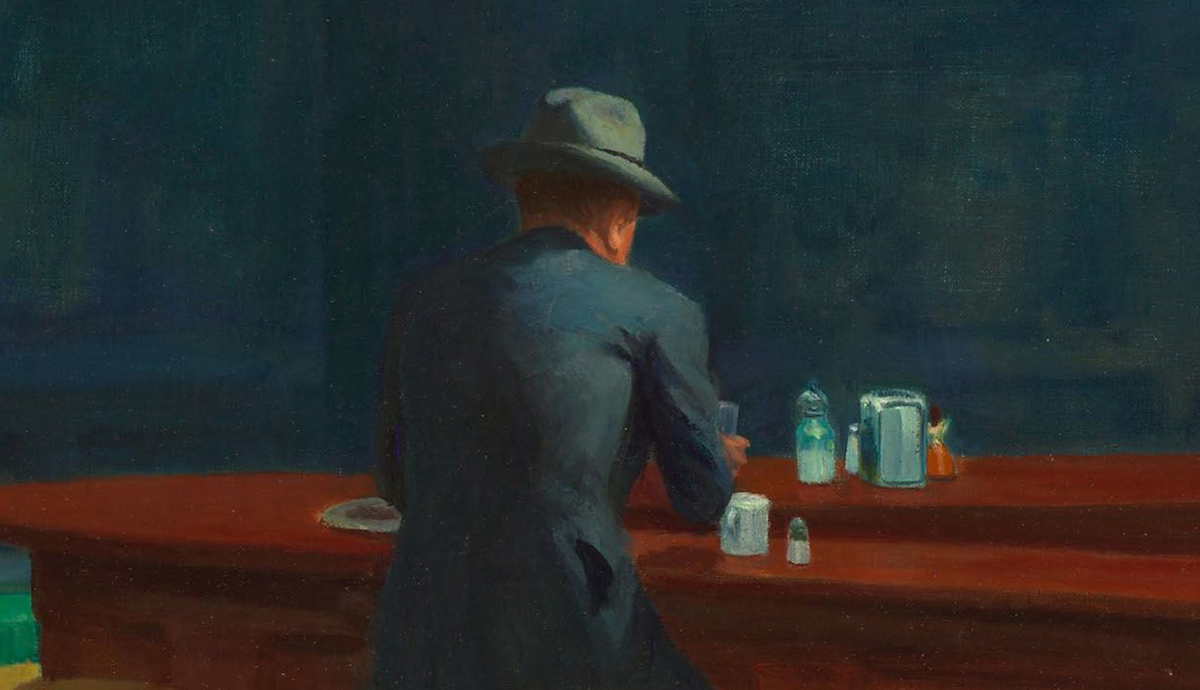

It was late and everyone had left the bar except me. I was sitting at a table near the window. It was snowing, and I liked to watch the falling snowflakes play against the streetlights. The view of the snow was good, and it was a pleasant way to pass the time. I liked this bar, because it was clean and because the lighting was soft and didn’t hurt my eyes. I felt comfortable there. I came almost every night to sit and drink by myself. I’d been drinking brandy. I was a little drunk, but I wasn’t showing it. I didn’t make any scenes, just sat there, enjoying the snow falling slowly. It was a little past midnight, near closing time. I wasn’t ready to leave, though. I didn’t want to go home to my empty apartment. It would take me a long time to fall asleep, and so I would be stuck with my thoughts and memories. I would be alone with my aloneness. That’s harder when you get old.

The waiter came up to me.

“It’s time to go home, pop,” he said. “We’re closing.”

“Can I have one more?” I asked. That’s all I wanted. Just one more. To help me sleep when I got home.

“Afraid not.” He looked at his watch.

“But I’m a good customer,” I said. “You know that. I never make any trouble. I just want to sit a little bit longer.”

“Go home, pop,” he said. “I don’t want you to slip and fall on your way home.”

“Just one more,” I said.

“No can do,” the waiter said.

I feared the nighttime. That’s when being alone stalked me. It grabbed me by the throat.

The owner, behind the bar, was at the till, counting out. He was a lot older than my waiter, and he usually had a kind word for me.

“Let him stay until we leave,” the owner said. “Give him one more.”

The waiter went over to the owner, and they proceeded to have a conversation I couldn’t hear. I was grateful for the extra time before I had to leave and go back to my dark apartment. I couldn’t afford to leave the lights on, so when I went home, I was confronted by dark. How dispiriting that is. It always hits me like a slap in the face, opening the door to the dark apartment. It’s a little thing, but it always gets to me.

⚈

I put myself directly inside Ernest Hemingway’s short story, “A Clean, Well-lighted Place,” because sooner or later something like this will happen to me.

I put myself directly inside Ernest Hemingway’s short story, “A Clean, Well-lighted Place,” because sooner or later something like this will happen to me. I will be somewhere, sometime, when I’ll want to stay until, and even beyond, closing time. Because it will help assuage the loneliness in my old age. I’m 76. I have no wife to come home to. Just to be among people helps so much. Maybe it will be a bar. Maybe it will be a restaurant. It might even be a store. And if it isn’t a matter of staying late somewhere, it will be another situation where it will be a matter of me being treated decently. At a supermarket, convenience store, car repair shop, department store, pharmacy. Where, being old, people can sense my defenselessness. They can, if they wish, ignore me, take advantage of my slowness, my inability to locate things, my inability to articulate what exactly I want.

“An old man is a nasty thing,” one of the waiters in the Hemingway short story says.

He’s not alone in his opinion.

“Not always,” says the older waiter.

Hemingway’s story, on the surface so dark and cynical, always makes me feel hopeful. The story is about dignity. Dignity is a concept that is most always in the hands of the giver. It is bestowed. A few people have a dignity to them that can’t be taken away, that is strong and sure and goes beyond social status. But for many of us, dignity can be stripped away quickly, because it so often relies on the giver’s unspoken acknowledgement that the receiver merits it—or that any human merits it. Thus it is the most delicate of graces, and as you get older it can become threatened and withheld. Anyone can withhold it at any time for any reason, and the older you are, the more frequent this seems to happen or can happen. With no dignity bestowed upon you, others feel free to heap scorn upon you.

Being old puts you more and more in the hands of others. You need help doing things. Others have to do them for you. But none is so powerful as the simple idea that you retain a certain dignity that is acknowledged, that is sacred. Too often, that is not the case.

I hope I don’t do anything not to deserve the bestowing of dignity. I hope I’m not petulant, disheveled, sloppy. Then I will have less sympathy for me and for people not granting me that sense of dignity. Our father who art in nada, please don’t let me be one of those old men who bring sourness into any room they enter. Who sits alone at a table in a café and looks sullen, unhappy and bitter. Who complains to the waitress about everything. Who you don’t want to look at because their face will taint your own joy. Who doesn’t understand the gift they’ve been given, of life. I pray that I don’t become that person.

Hemingway’s story gives me hope because it tells me there are people out there who will be looking out for me. Who won’t take advantage of the helplessness of my being old, especially when I’m in deep old age. Who will treat me decently. There will be those who won’t, of course. They’ll be the ones to ask me to leave.

“An old man is a nasty thing,” the waiter says.

“Not always,” says the older waiter.

I just have to find the right bar. The one that is a clean, well-lighted place owned by someone who understands that some of us, as we grow old, need a place to go. To stay just a bit longer before they have to go home.

Recommended

Encounter

Schizophrenic Sedona

Recense (realized)