“Let The Earth Be Lucky”: A Remembrance Of James Hearst

[B]urned in the bold air above you

in Black Hawk County

are the proudest words we can speak:

Here is a man.

Let the earth be lucky.

from Paul Engle’s poem “James Hearst” in the NAR Fall 1974 issue

“Time for bed, Carl. It’s late and you have a long day tomorrow.” That was the only time I heard James Hearst change his voice to try to sound like a woman. Hearst rubbed the stubble on his balding head and laughed. “Carl Sandburg and I stayed up late talking after our wives went to bed. About every hour, his wife came out of their bedroom to remind the great poet and biographer of Lincoln that it was time to hit the hay. But we were having way too much fun!”

I sat on the sofa in the Hearsts’ home (a museum now!) over fifty years ago. I hungrily munched cookies and gulped milk that Meryl Hearst carried out to us from their kitchen. She gave me a quick smile and wink as if to say: See? I told you he would be glad to talk to you and look at your poems.

I held tight to my three-ring binder (stuffed with about 200 poetic fragments that I was certain were seeds of great poems) like it was a flat football that I was afraid of fumbling. In 1964 I was offered a football scholarship to the University of Northern Iowa. I started as defensive back and returned punts on the freshman team coached by Dennis Remmert. The varsity coach was Stan Sheriff who only spoke to me once, after a game when I fumbled on a possible touchdown run. I’m not sure who I was more in awe of, Sheriff or Hearst! I never

expected to be sitting in the living room of a well-known poet who had actually published several books and was a good friend of Carl Sandburg, Robert Frost and Paul Engle.

“A guy I sit by in your class said you knew Robert Frost too.”

Without mentioning that his famous friend had died recently, Hearst smiled and rubbed his head again. “When we showed Frost our family farm, he just couldn’t get over how wide and flat the land was compared to those little rocky farms he knew in New Hampshire. He just stood there looking out over those acres of crops clear to the horizon, shaking his head and saying it was all too big.”

Without mentioning that his famous friend had died recently, Hearst smiled and rubbed his head again. “When we showed Frost our family farm, he just couldn’t get over how wide and flat the land was compared to those little rocky farms he knew in New Hampshire. He just stood there looking out over those acres of crops clear to the horizon, shaking his head and saying it was all too big.”

“Did Sandburg and Frost influence your own poetry?”

“I can see why you might think so, but no, they didn’t. The one writer who really influenced me the most was the Irish poet and playwright John Synge. He was good friend of Yeats. Synge loved nature too, and he wanted to write poems and plays from everyday life

that the common man could understand. Writing is hard everyday work, too, like farming and sports. Frost once told me in his deep voice, ‘Never let them know how hard it is to write a good poem, Jim.’”

Kenneth Lash, in his introduction to the North American Review’s 1974 tribute issue to James Hearst, talked about how hard Hearst worked both as a farmer and a poet. Then Lash mentioned the softer side of Hearst: “The softness is in the generosity.”

I sat there watching James Hearst read my first real efforts at writing poetry. I was nervous. He could be tough in class. The textbook we used, an introduction to literature, was written by his friend H. W. Reninger. Mr. Hearst knew it from cover to cover. He also knew if we had done our assignments and insisted that we do our best. He graded fairly, letting us redo our written papers when necessary.

Perched on his sofa, eating his wife’s cookies, I started to worry about bothering an already busy man, who had accomplished so much as farmer, poet, and teacher, all while using a wheelchair for most of his adult life.

But then Mr. Hearst read a few lines of mine out loud and said he liked a phrase or two and several images that “worked pretty well.” He laughed at my obvious attempts at humor. I could see he was trying to find some good things to say to me. He probably only read a couple dozen of those early long-fragments that day.

“Many of your poems are two or three different poems rolled into one, all fighting for attention. Try to find out what your poem is trying to say, then look for a clear and simple way to say it in your own voice like you’re talking to a friend. I know that’s not easy. It took me about

twenty years to find out what I think is my real voice!”

He handed my three-ring binder back to me. “Don’t take all day saying what you want to say once you figure out what that is. Just come right out with it and see where it takes you.”

Generosity. James Hearst had plenty of that, to go along with his toughness and a farmer’s habits of working hard and doing your best.

As I was leaving his home that night and thanking his wife for the milk and cookies, the teacher came out in James Hearst when he reminded me to try to go hear his friend Paul Engle give an upcoming lecture in the Old Main auditorium on campus.

So thanks to Hearst I did get to hear Paul Engle speak about what it means to be a poet. The one memory I took away from that lecture was Engle saying: “Read all the poetry from all the great writers over the years and learn what you can from them. But never forget those lonely beginners struggling to write good poems up in stuffy attics somewhere, when no one believes they can do it but themselves. Respect and honor their efforts too, no matter how they turn out.”

In 2005, thanks to Hearst and Engle, I published a poem in The Hollins Critic, at Hollins University in Virginia, titled “Up In The Attic,” which is in my first book of poems that my brother Barry and I published by 1st World Publishing in 2009 titled Schooled Lives: Poems By Two Brothers. We were partly inspired by the Tennyson brothers who did the same thing in 1827. Our book was reviewed very favorably by Vince Gotera in the North American Review, and in 2015, our second book of poems, Poems by the Skunk River Valley Boys, was published by Blue Light Press.

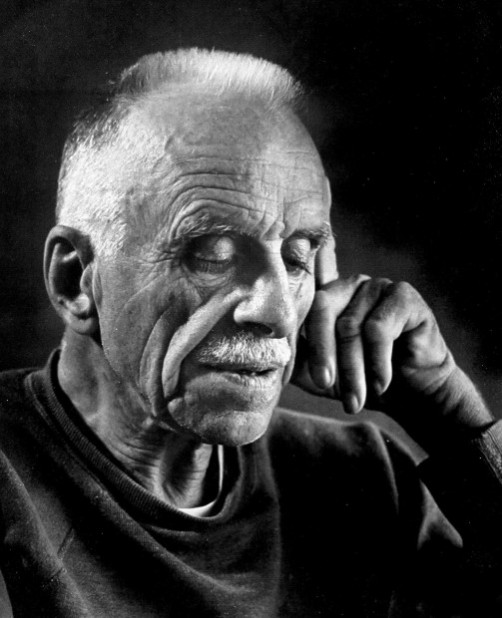

I still have my well-worn copy of the 1974 issue of the NAR’s tribute to James Hearst. I like to study Hearst’s face on the cover looking at us through tired eyes, with his chin resting on his two clenched hands, and his white stubble of sunlit hair. His right eyebrow is raised as if to say: It’s not easy to be a good poet or a good anything. It takes study, hard work, luck, and some humor helps. Try to do your best every day and good things can happen.

Recommended

Mercy

Eclipsing

Psychic Numbing