"The Literary Rub"

“The Tough Guy Test” (Winter 2017) is the second story North American Review has published from my collection Bridge & Tunnel. In it, a woman returns to her working-class roots in Queens after the Great Recession, her manor-born husband and their toddler in tow. The husband’s adjustment is an immediate challenge, and ultimately the woman must confront the subtler shifts in her own perspective. It is, in the context of the current moment, a story about the power of social bubbles and the difficulty of transcending them.

My collection predates the current interest in social bubbles generated by the results of the presidential election, but I have always been aware of them. I am the overeducated child of dislocated factory workers from the now-gentrified neighborhoods of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and Ridgewood, Queens. I have post-college friends who live in buildings where my parents, now deceased, once worked. The industrial blocks of my childhood have been transformed to suit my own fantasies of what a neighborhood should be—full of restaurants, used bookstores, and other literary, social, and cultural spaces—but this change has not served my family, most of whom have been forced to move by escalating rents that were already a challenge on service-industry wages. Most of the relatives and neighbors I was raised amongst have not thrived in a post-industrial economy or transcended the education/opportunity gap.

When I return to the streets of my youth, worlds collide. The mix is, at best, tight-lipped and tense. My friends of greater privilege are sometimes guilty of enthusiastic social-slumming. They want to visit authentic local spots to observe this other world they live near, yet do not occupy. They listen wide-eyed to confessions, gossip, or talk about the good ol’ days, as long as the rhetoric doesn’t stray too far right or connect their presence in the neighborhood to any narrative of personal decline.

In mixed company, my relatives gleefully regurgitate conservative talk-radio sound bites, although my own experience of them as people isn’t hateful, and our private relationships avoid confrontational topics. My friends, largely NYC transplants, fear dismissal as real New Yorkers in the presence of those who are hardscrabble born and bred. My relatives, who have never experienced much success or approval in places with institutional authority—school, work, government—are hostile to any perceived intellectual or social slight. I have only come to recognize this sensitivity slowly, over time. In my youth and ignorance, I actively triggered it. In any us vs. them narrative, I’ve long since changed sides. If I desire to be a bridge between these worlds, I must admit I’ve done a poor job anywhere but on the page.

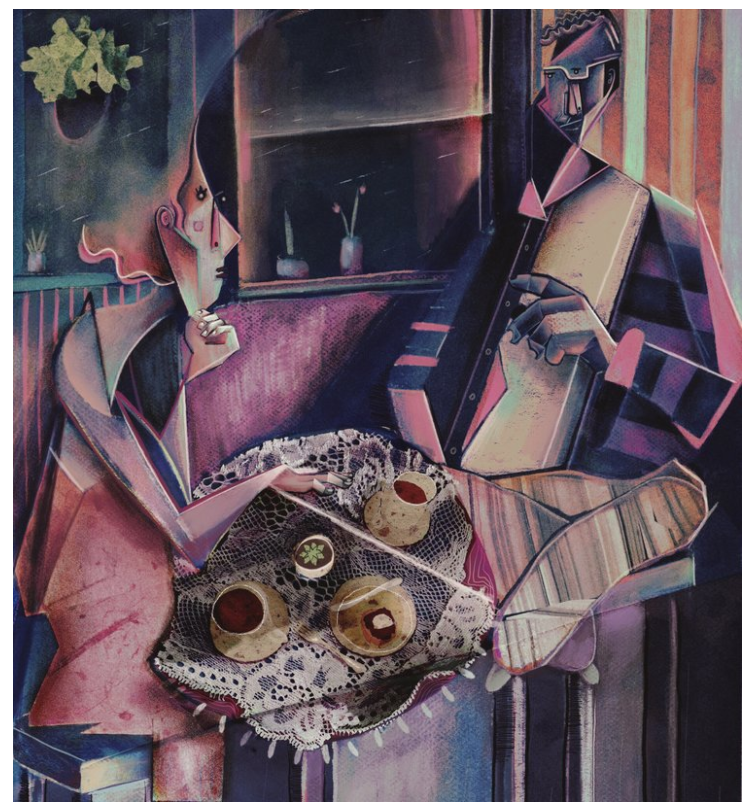

In Rome, the customary Italian evening stroll referred to as la passeggiata is also called il struscio, which means “the rub.” As a New York City native, I’ve always appreciated that nod to urban life. In a densely-populated city, strolling means rubbing up against the strange and the new. Rubbing creates friction, which is uncomfortable, but also releases energy in the form of static electricity. Every rub has the potential to be powerful. Il struscio was the inspiration for Bridge & Tunnel. I created a literary rub, a book of stories where social worlds collide. I sought to tell these stories with complexity and compassion, knowing just how often I’ve come up short in real life. I do so because I believe in the transformative power of literature. If I’ve slowly become a more tolerant, compassionate version of myself, it has happened through a life experienced on and off the page.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop