Live with a Poem

It’s the last day of my introductory poetry writing class, and my students are giving their recitations and presentations for a final project I call “Live with a Poem.” One student, originally from Singapore, has chosen Carol Ann Duffy’s “In Your Mind.” She offers highlights from a conversation with her friend, another international student, about how the poem speaks to the experience of living in a foreign country. The next student, after doggedly making his way through his recitation of Richard Siken’s long and sinuous “Saying Your Names,” presents a slideshow of photographs he’s taken in an attempt to capture the poem’s mood, which he describes as one of “intimate distance.” I’ve had student’s pair poems with pieces of music, wear them on T-shirts, and use them as inspiration for oil paintings. One person even did a statistical analysis based on the lines in his poem of choice, that passersby responded to the most. The assignment is to choose a poem that’s personally meaningful to you, and then “live” with that poem by incorporating it into your life in a creative way.

Like many of us, the majority of my students were introduced to poetry in high school English classes, where they were taught to analyze poems rigorously. While it’s true that examining a poem’s symbols or researching its historical context can help deepen our understanding of it, I believe we need to cultivate a basic respect for beauty and mystery in poetry as well. In his poem “Introduction to Poetry,” Billy Collins asks students to “drop a mouse into a poem/and watch him probe his way out” or “walk inside the poem’s room/and feel the walls for a light switch”. It’s hard to imagine reading this kind of description in an academic paper, because it isn’t the phraseology of analysis. It’s the language of appreciation. When I ask students to “live with a poem,” I’m asking them to tap into that way of thinking. I’m asking them to treat poems not like machines that need to be taken apart, but as spaces that deserve to be lived in and explored.

Many people feel that all poetry is “over their heads.” One of the biggest forces that can separate us from a poem is anxiety about What It Really Means. If we approach the reading experience as an exploration, rather than as a problem-solving process, we can overcome some of that anxiety. Reading poetry requires an alertness to beauty, and I believe that looking at a poem’s musicality and imagery, temporarily divorced from their significance, can be a good way to cut through our fears. When we’re attempting to make sense of Sylvia Plath or Wallace Stevens during class discussions, I’ll sometimes ask my students to pause: “For just a minute, let’s forget about trying to figure out what this poem means. Can you tell me something you find beautiful about it?”

But I also want my students to realize that their confusion is a great place to start. The more they embrace and investigate a poem’s ambiguities, the more likely it will become meaningful to them. This kind of exploration takes time. When I ask students to “live with a poem,” I’m primarily asking them to spend time with it. As one student wrote in her final reflection, “I’ve learned that you can’t just read a poem once if you want to understand, or even enjoy it…Throughout the semester, I’ve come to really enjoy the process of sitting with a poem and trying to uncover the images, emotions, and meanings that are hidden within—almost like a little puzzle.” She adds, “There still are a lot of poems that I, frankly, do not understand. But this doesn’t frustrate me like it did in high school. I’m okay with not understanding everything. It makes me think the poem holds secrets only the poet can find.”

What I like most about her reflection is that she doesn’t pretend her confusion has gone away. Instead, she acknowledges that it’s been transformed into something more pleasurable. I like to introduce my students to Keats’ frequently cited “negative capability,” which he defines as “being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.” Particularly in academic settings, we’re conditioned to see any type of confusion or uncertainty as negative. But reading and writing poetry requires an openness to a kind of positive bewilderment.

Ultimately, when we read poems, I believe we should seek not only to apprehend their meaning, but to allow them to fundamentally change us. Through careful attention to their beauty and mystery, we can cultivate a deeper respect for poetry—one that comes not from a self-deprecating awe at the writer’s intelligence (“He or she is so smart to have made this poem that I couldn’t understand at first!”), but from poetry’s ability to open us up and make us feel something. I believe that this kind of appreciation needs to be taught. When students experience poetry only in traditional academic settings, they learn that poems are meant to be approached solely from an intellectual angle, not an emotional one. But poems have an incredible capacity to move us, if we are open to being moved. As Emily Dickinson wrote, “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?”

Lindsay Stuart Hill is an MFA candidate at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, where she was recently awarded the Academy of American Poets Prize. Her work has appeared in Ploughshares, Five Points, North American Review, and The Norton Pocket Book of Writing by Students. Her chapbook, One Life, was published by Finishing Line Press. Lindsay appeared in issue 298.4, Fall 2013.

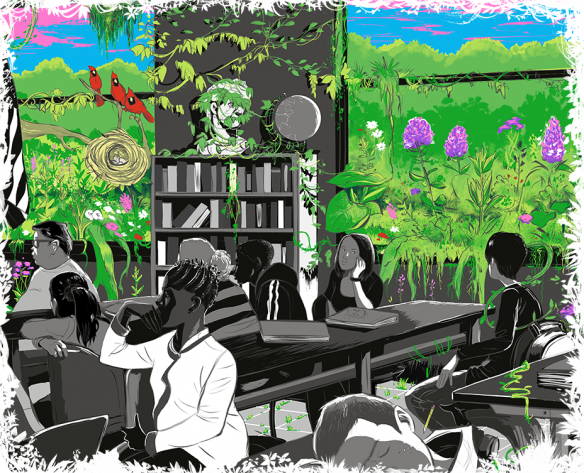

Illustration by: Ryan Inzana is an illustrator and comic artist whose work has appeared in numerous magazines, ad campaigns, books and various other media all over the world. His graphic novel Ichiro was the honor selection for the Asian/Pacific American award for young adult literature and was also nominated for an Eisner. You can see more of his work at www.ryaninzana.com.

Recommended

The Shirt

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings