Loving the Alien

People ask at readings where writers get their ideas. Here’s one that fell from the sky, flickering in black and white.

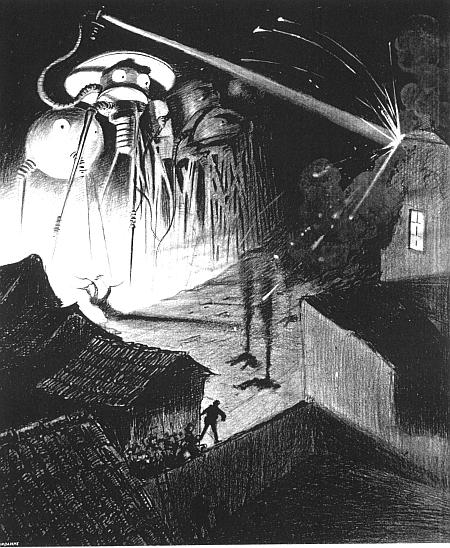

I watched enough old sci-fi movies as a kid that the plots and settings blended together into a single 1950s sci-fi world. That world is a small town in the American Southwest, surrounded by endless stretches of desert and mountains, an arid wonderland where stray objects—flying saucers, meteors with transformative powers—tend to crash and glow, attracting an old homesteader or a young couple making out in Dad’s Bel-Air on a moonless night. Soon, a malevolent new creature scuttles from the crash site and out of the wasteland. Panic. A state of emergency. The Jeeps roll in from the nearby base, the soldiers’ bullets but pathetic displays of useless aggression from primitive monkeyboys. Fortunately, there’s a scientist in town, a man with answers—at least the ones a human mind can know. First he must fall in love with the local school teacher/librarian/research assistant so he has someone to worry for him. The scientist’s dangerous stratagem puts him in mortal danger. It must be executed with radical precision and the grudging help of the military, or else the world as we know it will either cease to exist or will fall under the control of a robotic and heartless hyper-intelligence.

SPOILER: It’s not really over when the scientist saves the day; there are more aliens and magical meteors ready to fall.

MORAL: The universe will continue to spit out its horrific wonders while the scientists work to keep us safe.

In 1997, I’d just moved to California for a teaching job. I was an alien myself, having lived back East all my life. But I was no threat to take over the Bay Area, and the best I could do for magical powers was to create miniature word-worlds, borrowing more or less from life and art. In the case of my first West Coast story, I borrowed from those sci-fi movies, the fairy tales of my childhood.

Inhabiting that 1950s sci-fi world opened up imaginative doors. Instead of pulling characters out of the mess of real life and trying to scrub them, mold them, and dress them into fictional characters, I was plucking beautiful lights from the firmament and yanking them back to earth. They were forms to be humanized, ideals to be dirtied and oxidized. I gave them warts.

Pulling from the tar or plucking from the sky: two very different methods of creating characters. In either case, one hopes the results settle nicely into the in-between land of fiction.

I rearranged the furniture of the sci-fi world and made the place my own. I even threw in a posse from another of my childhood favorites, the Frankenstein movies. The outcome was “Xenophilia,” an operatic, multi-voiced story of a little desert town lusting after aliens. The writing wasn’t easy, but it was charged with some sort of pulsing otherworldly energy all the way through. Or at least that’s how I’d like to remember it.

“Xenophilia” came to me out of the sky like one of those horrific little wonders I must, like those scientists in my sci-fi world, find a way to tame. I saved the world that time from certain destruction. Who knows if I can do it again?

Reader, I’m prepared. I’ve married the school teacher.

John Henry Fleming’s story collection, Songs for the Deaf, was recently published by Burrow Press and features “Xenophilia” (283.5) and “Weighing of the Heart” (284.6), both of which appeared originally in The North American Review. He’s also the author of Fearsome Creatures of Florida, a literary bestiary, The Book I Will Write, a novel-in-emails originally published serially at the Atticus Books website, and The Legend of the Barefoot Mailman, a novel soon to be re-released in a 20th Anniversary Edition.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop