Me and World War I

I first heard of World War I when we came to America as Displaced Persons in 1951. We were refugees after World War II, and we moved into a basement apartment on Hamilton Street in Chicago.

Our landlord was a veteran of the World War I. He was a Polish-American named Ponchek. He was also a drunk, but that wasn't anything special. There were a lot of drunks around. What made Ponchek special was that he had a steel plate in his head. As a kid and a recent immigrant to America, he was drafted and sent to France to stop the Germans who were trying to rip France apart and shove it into the Atlantic. He ended up in the trenches in France in late October of 1917 fighting the Germans, and a bullet took off the top of his head. The doctors cut away what bone they could, cleaned out the wound, and screwed a steel plate into the bone of his skull.

This fascinated me when I was a kid. I wondered a lot about that plate and what it felt like. Did Ponchek always feel a weight pressing down on his head? Was it like wearing a steel hat? A steel helmet? And I wondered what they covered the plate with. Skin? And where did it come from? Was it his skin or someone else's? I never could ask.

Like a lot of the veterans I knew, he was frightening. He wasn't a guy you wanted to spend a lot of time talking to.

Veterans were men who limped. They dragged their legs behind them like Lon Chaney in the Mummy movies. They were men who had wooden legs that creaked when they walked past you and the other kids sitting on the stoop. These veterans had no arms or only one arm, or were missing fingers or hands, or ears.

My dad, a guy who lost his left eye when he was clubbed by a Nazi guard in a concentration camp, used to go to a bar where the owner had a black, shiny rubber hand. He lost his real hand during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944 when he shoved a homemade grenade into the steel treads of a German tank. The black rubber hand was like some kind of weird toy. Sometimes, it looked like a black fist, sometimes it looked like an eight ball.

A lot of times, a guy without arms or legs sat in front of this bar. He had a cloth hat in front of him, and he sold pencils. He'd sit there smiling, making chitchat with the guys walking in and out of the bar. You'd toss him a nickel, and you could take a pencil, but most guys didn't. Who needed a pencil?

Veterans were frightening. They were men who beat their kids and got drunk and had trouble getting through the day. They had trouble getting through the night too. There were these two little girls who lived two doors away, Patty and Cathy. Their dad was a Korean War veteran, and he would come home from his job at about midnight. The kids and their mom had to be out of their basement apartment then. He would beat and curse all of them if they weren't. They'd have to walk around the neighborhood until he was safely in bed, asleep. This veteran didn't like to fall asleep with people in the house. Everyone knew he was crazy.

Ponchek was a veteran, too, and-like I said-he was a drunk and a man with a steel plate in his head. One time he and his two buddies got so drunk that they all came down to our basement apartment and tried to force my mother into giving them money for whiskey. There she was alone in a house with her two little kids, me and my sister Danusha, and this drunk and his two drunk buddies came around trying to take money from her. Ponchek told my mom that she hadn't paid the rent, and that if she didn't pay him, he would throw her out on the street.

What kind of guy would do that?

My mom was a pretty tough woman who had survived 3 years as a slave laborer in Nazi Germany. She pushed Ponchek down and kicked him, and she took a broom and beat him and his friends as they tried to get away from her. My mom was a veteran too; she survived two and a half years in a slave labor camp.

Three or four years later, my mom and dad and my sister and me visited Ponchek in the big Veterans Administration hospital on the south side of Chicago. We didn't have a car, and so we had to take buses, and it seemed like it took forever to get to the hospital. This must have been about 1956 or 1957. The hospital was full of veterans, men from World War I and World War II and the Korean War.

Ponchek was dying of some kind of stomach cancer, and he was in a lot of pain. We came to say goodbye to him. We found him in a bed in the corridor because there were no available rooms.

He sure was happy to see us. My parents had brought him some cigarettes, and my dad gave him one and lit it for him. My sister and I stood there watching my mom and dad and Ponchek smoke and talk. They talked about those days on Hamilton and the good times they had.

They didn't mention his steel plate and his drinking and his craziness.

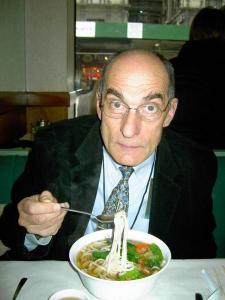

Illustration by: Daniel Zender.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop