Movieverse

In my universe of Belgian children, some were orphaned, but many were abandoned by families left destitute in a worldwide depression or by unmarried women ashamed of being “in the family way.” The nineteen-thirties in Europe, as elsewhere, was an unforgiving time. I was parceled out by my French mother to the L’Institut de Puericulture in Brussels, a municipal orphanage presided over by Catholic Sisters of Charity, and stayed there for almost eight years. Certainly, I never saw a movie, although clues to their existence were left in glossy magazines that were sometimes forgotten or discarded by visitors who came on Sunday afternoons. On the covers were women with pale waved hair, and bright red lips. I learned they were vedettes, movie stars glittering from another world.

Under the watchful eye of nuns, we knelt in chapel for Matins, scraped our bowls of porridge, and took our seats in a classroom that fascinated me with its roll down map of pastel colored countries and blue oceans. We copied white words printed on a blackboard into soft blue books, dipping our pens into inkwells.

Our days ended as they had begun. Led into chapel we knelt at Evensong, chanted solemn prayers at dusk, formed a line and soon after ended our day in a long L-shaped room, eight beds on each side, a crucifix, I forget just where on the wall, to remind us of Christ’s sacrifice.

A scattering of boys, sought-after by couples who needed extra hands on the farm gradually disappeared. After lunch of mutton, cabbage, kale, the main meal of the day, we girls were often assigned to a large airy room where we embroidered doilies, handkerchiefs and tea towels for sale to our African mission. I thought we labored for Africa, a great tongue-shaped continent on our roll down map.

Sometimes in winter small groups of us were taken in a van to a nearby frozen pond where we strapped on skates. I still recall the excitement, the element of danger and exhilaration, qualities lacking when we were later introduced to jump rope, a sport the Sisters agreed would not cause quarreling or spitefulness. Toys and the exchange of gifts were forbidden; they would cause jealousies and rancor especially among children not yet skilled at self-restraint. My own mother, who came to see me in the guise of a distant auntie, once brought me a stuffed toy which was swiftly taken away. No toys allowed.

Our possession were few and stored in a communal closet: summer and winter uniforms, caps, shoes, knee socks, scratchy muslin under wear and one pretty white dress, hand sewn with a deep hem. I am not sure whether I had heard of Shirley Temple the dimpled child star of Hollywood but she was of that time and the dress would have suited her earnest and determined spirit. I wore it for my First Communion, an initiation into the mysteries of the Holy Roman Catholic Church.

My life at the institute ended abruptly one day in April of 1938 when two strange men came to take me to Antwerp where we were to board a ship to England and then on to America. The men, one a lawyer, the other a professor, were to arrange for my adoption by woman from California, someone who knew my family. Like the nuns, the men were not forthcoming when I stammered questions about that family. Where were they? Would I meet them in America? Why had I been left here when they were there all this time?

There were movies on the ship. Was it Charlie Chaplin whose sad, tilted face and stammering walk made me pity him? I remember not laughing when the audience roared with pleasure. That square of light flashing black and white images astonished me even as I did not understand the language being hurled into the room, or the unhappy story unfolding.

Chaplin whose sad, tilted face and stammering walk made me pity him? I remember not laughing when the audience roared with pleasure. That square of light flashing black and white images astonished me even as I did not understand the language being hurled into the room, or the unhappy story unfolding.

As it turned out, the woman from California did not for complicated reasons want to take me with her to the Golden State and I landed with a couple on Long Island, a pair just beginning a steep decline into the disarray of booze and early death. But in the backdrop was the Gables Movie Theater on Merrick Road, and for twenty-five cents on Saturday afternoon by the early nineteen-forties I could watch two movies, a preview and sometimes a cartoon. I recall my first meeting with Mickey Mouse in buttoned trousers, and that I had actually seen a real mouse at the institute, a small gray skittery creature eliciting screams as it raced across our bare floor. Donald Duck in his sailor suit, and muscle bound Popeye’s pep talk for spinach left me cold.

Around that time I began to spend summers in Cleveland with a Midwestern branch of my American family and it was there I learned about movie stars of an earlier generation, those before the “talkies,” Rudolph Valentino whose too-early death gathered flocks of mourners to his grave. Theda Bara, Pola Negri, even the names enticed me. The man who headed that Cleveland household tuned pianos for the theater trade. He had an eager audience in me for his recollections of nickelodeons, The Perils of Pauline, Buster Keaton, W.C, Fields, films and stars of a celluloid age, an era when even the august Russian composer Shostakovich, to pay the bills, pounded piano keys in movie houses of Leningrad.

There were no movie houses on Monhegan Island, Maine, when in 1962 I first met my husband, Saul. Looking up at stars at the edge of the sea, he said “The work of the universe is never done,” and I was won over by this grand and sweeping phrase which now alas, is subject to wrangling. Is this the only universe, the infinitely infinite one of Spinoza’s definition? Are we part of a multiverse? Are we “glorious accidents?” And are we alone? A thousand exoskeletal planets have recently been discovered. Fifty-one years later, in a lucky marriage, Saul and I are still querying and going to the movies.

On a bus tour of Mexico in 1965, we stayed over in Cuernavaca and looked for a restaurant listed in a Frommer’s Guide in which Las Manaitas came highly recommended. Surrounded with preening peacocks and candlelight, we enjoyed savory Mexican food. On our way out, we noticed a flurry of attention in one of the side pavilions. “It’s Dolores Del Rio” someone said, and so it was. Her eyebrows in a perfect oval face were still the lovely winged arcs I had admired in photographs. On another note, one of Orson Welles’s daughters visits a poet friend of mine in Delray Beach. And Rita Hayworth, the mother of another Welles daughter, appeared in “Gilda,” a sizzling movie heating up the screen on my first date at The Gables movie theater. Popcorn, cherry cokes, the velvety dark, it was a universe far away from my humble beginnings.

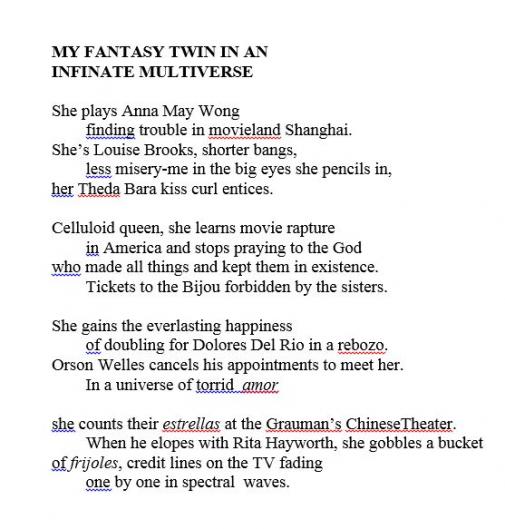

Illustrations by Junyoung Kim. Junyoung Kim is an illustrator, cartoonist, and printmaker based in New York. She graduated from the School of Visual Arts with a BFA in illustration. Her works are featurd in various magazines including the Visual Opinion, GrowerTalk, and Green Profit magazine.

Find more of Junyoung’s work here.

Recommended

Mercy

Eclipsing

Psychic Numbing