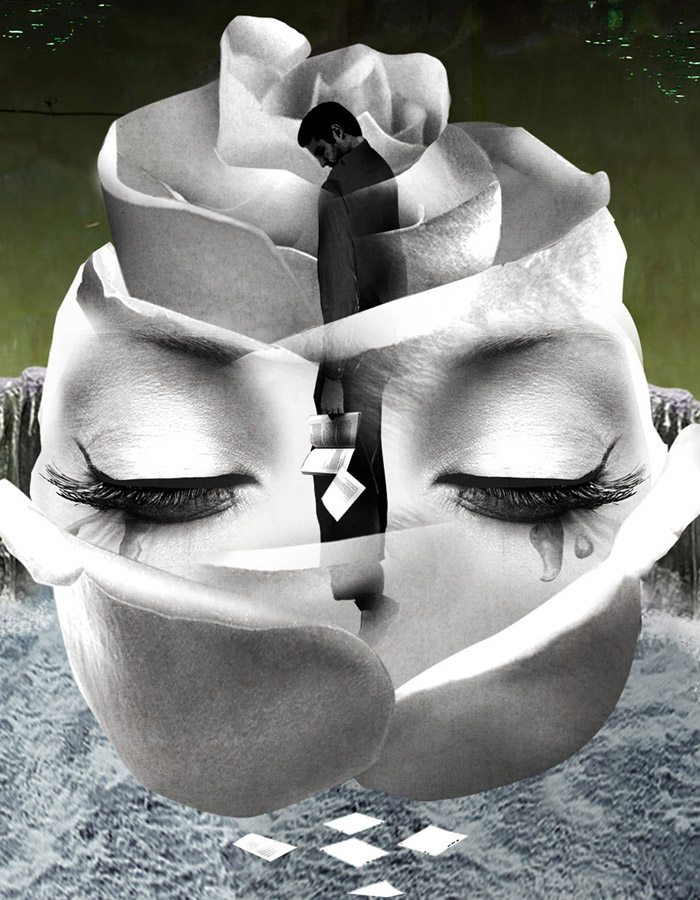

My Unapologetic Ode to Melodrama

One of my favorite quotes is from Robert Frost: “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader.” Yet many of the writers I know shy away from anything “teary” for fear that their work might be seen as (cringe!) melodramatic. But the trouble with shying away from drama (for fear of melodrama) is that it often stifles you before you go to where you need to go in your story. Often to find the beating heart of a story, the part where our throat tightens and our pulse quickens oy, I know! Bear with me! We need to allow ourselves to venture way, way outside our comfort zone, into the arena of melodrama.

We can loosely define melodrama as unearned emotion in a story. To resolve melodrama is not to avoid emotion in the story, but instead to make the emotion earned. But before we can make the emotion earned, we first need to discover it.

Ah yes, I can feel you all recoiling from here! As fiction writers, we are a tough bunch. We endure hours upon hours of solitude, generally scraped from the sides of busy lives filled with families and friends and work. We toil for months, sometimes years on a piece, writing draft after draft after draft while we ruthlessly edit and hold in a breath while we kill our darling all to face the seemingly endless rejection when it comes time to publish. The last thing we want is to be accused of sentimentality. Tell us our dialogue is stilted and we can take it. Tell us our structure needs work and we get out our metaphorical hammer and nails. Tell us our plot is thin and likely we’ll see it as a compliment and then try and beef it up. But tell us we’re melodramatic? Now you’re hitting too close to home.

Ah yes, I can feel you all recoiling from here! As fiction writers, we are a tough bunch. We endure hours upon hours of solitude, generally scraped from the sides of busy lives filled with families and friends and work. We toil for months, sometimes years on a piece, writing draft after draft after draft while we ruthlessly edit and hold in a breath while we kill our darling all to face the seemingly endless rejection when it comes time to publish. The last thing we want is to be accused of sentimentality. Tell us our dialogue is stilted and we can take it. Tell us our structure needs work and we get out our metaphorical hammer and nails. Tell us our plot is thin and likely we’ll see it as a compliment and then try and beef it up. But tell us we’re melodramatic? Now you’re hitting too close to home.

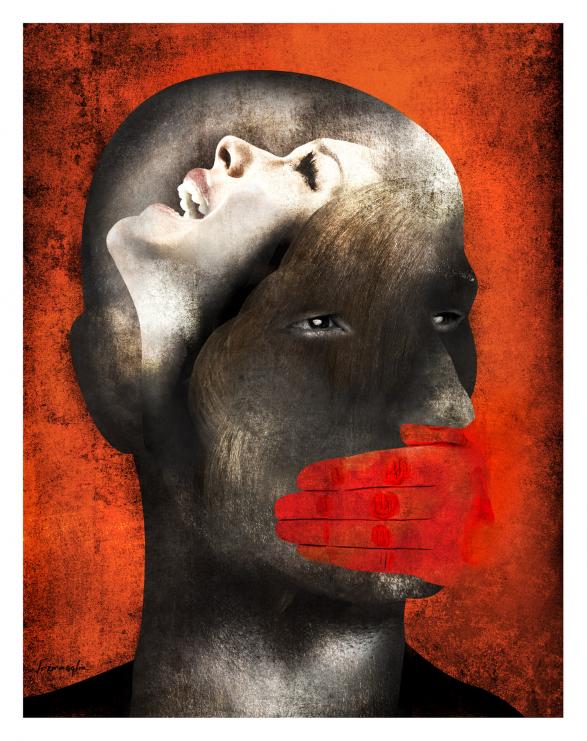

We all know that the writer needs to tap into themselves to create a character with whom readers can empathize—but this is the danger zone where fiction and fact blur. To write about loneliness or heartbreak is tantamount to admitting (or revisiting) our own. Though the story might be crafted entirely from fairy dust and cattails, the emotions we map to the page, I daresay, are not fictive at all. I’ve come to think that shying away from drama is from a fear to expose or provoke something that is deep and private within ourselves. Unwittingly, we shield ourselves and thus shield our characters. We don’t push ourselves to make that painful discovery, and thus our characters never discover this and thus our readers don’t experience this, either.

It’s easier to be restrained, to hide behind the veil of “literary” as if that means unemotional. But let’s face it – there’s a reason we all read literary fiction, and it ain’t the plot. We crave these stories so that we might inhabit an external world that reflects our internal experiences, our loneliness and confusion and desire and hope. We read to understand something further about human nature or truths in this world, to glimpse beauty, understand fear, to know that someone else has survived what we are trying to survive. We yearn to be moved. We are epiphany seekers. (We are amongst friends, and we can admit it!)

So, given this, how can we expand the (imaginary! self-imposed!) boundaries in own work? You can start by asking some questions. What’s the emotional core of the story? What does your character fear the most? What does she yearn for the most? What are the forces working against her in this journey? In other words, there’s got to be something your character wants, and wants desperately. This yearning drives the story. The forces working against her this is the tension in the story. These questions can lead you to the brink of melodrama. Well I am here to say: cross that line. Yes, this may include canned writing, loaded words that tell us how to feel rather than graceful sentences that elicit feelings or >shivers< clichés. Write past it. Embrace melodrama!

At least in your draft. Go there. Push past all the comfortable and reasonable words on your page, go into this unchartered territory. It is there you will often discover the thing that surprises you about your character or story, the brutal and honest gem you would never have discovered if you kept yourself restrained from exploring the outerbanks of drama.

Once you discover this gem, you can bring this new knowledge back to the story, and pare back the drama you’ve written. Sculpt. But you can’t sculpt something not there.

Literary fiction traditionally contains one “moved” character usually the point-of-view character who experiences the events in the story, and then is moved to epiphany at the end. In order for us, as writers, to write this epiphany, we first have to discover it. I believe that we discover this turning point of the story through setting ourselves free to draft in melodrama.

There is another quote I love, this by Marcel Proust: “Never be afraid to go too far, for the truth lies just beyond.” So as you draft, push through the words until you find your own emotion. You just might find that you move your reader to tears.

Illustrations by: Anthony Tremmaglia. Anthony Tremmaglia is an Ottawa-based illustrator, artist, and educator. His clients include WIRED, Scientific American, Smart Money, HOW, and San Francisco Weekly.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop