Name Your Name: On Male Confessional Poetry

The act of confession reveals the soft underbelly. But what are acceptable topics? I have heard a certain male writer is famous for saying Sharon Olds would be a great writer if she only got out of bed once in a while. I have been told many times by male teachers and fellow writers that no one wants to read about my experience as a daughter, mother, or lover. I have never heard of a man being told what he can and cannot write about. But for all of man’s innate freedoms, ones masculinity is essentially what is risked.

Take W.D. Snodgrass for instance. Time and time again, he presents speakers who are intensely vulnerable, risking seeming effeminate. In the first few stanzas of “April Inventory,” Snodgrass’s speaker laments his lack of knowledge in an industry that would result in a high paying job. This is essentially an androgynous problem, but for men, bringing home the bacon is connected directly to their manhood. His speaker says, “In one whole year I haven’t learned/ a blessed thing they pay you for.” Here, his speaker sets up a me/them dichotomy, asking his reader to take his side. And just because we are the sort of people who read poetry, we are automatically on his side. We know that Snodgrass himself struggled to find a permanent teaching position. (Who among us hasn’t?) He was fired from Cornell in 1958. (I bet they were kicking themselves for that when he won the Pulitzer two years later.) But even with a Pulitzer under his belt he bounced around the country quite a bit. These biographical facts insinuate that Snodgrass’s speaker is autobiographical, which is an important aspect of the Confessional poem.

Although, not all confessional poems need to have a speaker who is closely mirrored to the writer. John Berryman’s Dream Songs come to mind, for which Berryman uses a persona to “confess.” Use of a persona is a way to say what cannot be said, what shouldn’t be said, and maintain distance. Berryman’s persona, Henry, often dreams about being someone with confidence, who can talk to beautiful women and tell authorities off, things Berryman himself felt he couldn’t do. Henry also laments the aging process, and lacks self-esteem. He at times appears to be a modern-day recreation of Eliot’s Prufrock. In fact, there is a long tradition of men lamenting their lost looks and low self-esteem.

Snodgrass’s speaker also bemoans the aging process, likening his balding head to the trees going bare, his dry skin to falling blossoms, his teeth falling out like leaves. Here, the trees have more to give than he does, with the promise of renewal in spring. In real life, Snodgrass was thrice divorced by this time, which would have wreaked havoc on not only his emotions, lifestyle, and energy levels, but also his bank account. For a man, financial prowess is synonymous with masculinity. If this were a woman writing about the female aging process, she would be labeled vain. But for a man, it isn’t considered vanity, it’s virility. It’s connected to the life cycle in a way that is honored, not patronized as women's writing routinely is.

Like many men, Snodgrass’s speaker finds solace in action. He owns his confessions through teaching experience: how to relate to the natural world, how to love. This is chiefly the work good teachers, and, by extension, writers do. While these are not the things that will pay dollars, they are the stuff of life. Love and literature make life worth living.

In “April Inventory,” Snodgrass is calling out the irony painfully obvious to many Liberal Arts scholars and writers: being tuned in to the environment, to humanity, is never monetarily rewarded. Snodgrass’s speaker finds value not in his looks but in what he can convey to students, how he takes the world in and presents it to others. He finds value within rather than without.

The “starchy collars” and “ulcers on their sleeves” are not to be admired, even though their bank accounts may be. What’s ironic here is that the “solid scholars,” while rewarded handsomely monetarily, are not versed in the experience of living. Snodgrass’s speaker is accomplished in the act of lovemaking, in caring for the dying, in being proud of speaking his own name.

And he should be proud. This is quite an accomplishment for a man: to sing out of tune, go against the endless lines of traffic, to make ones own way. To listen to what the earth says, what the self says, that is truly living. Coming to this sort of monastic writing/teaching life isn’t for the faint of heart. Snodgrass proves this with all the elusive actions his speaker must take: to promise the parents, to become immune to the youthful, ripening female students, to focus inward rather than outward. Snodgrass shows this by making use of opposites and by turning images back onto themselves: blossoms/dandruff, trees/hair, teeth/trees, teeth/silver lining.

He also uses allusions to this end. He makes references to Whitehead’s notion in the 6th stanza. A.N. Whitehead was an American mathematician and philosopher. His theory of perception is that all entities experience: human, animal, elements. For Whitehead, one doesn’t have to have a mind in order to be conscious or unconscious. This is interesting when you think of how one perceives their life vs. how one is perceived. For the speaker of “April Inventory,” he is worth much more than he is paid. This is the case with many of the world’s true thinkers, and it’s a problem in society. How many macho football players can string two sentences together, much less create something beautiful, yet they are rewarded handsomely for their athletic ability while scholars live on government support and are wracked with debt? How many of us have told our parents, “if I just get this degree, publish this book, I’ll get the job,” “I’ll be substantial”? How do we explain having two advanced degrees, two or more poetry collections, a CV a mile long and nothing substantial to show for it? I, for one, continue to live with the endless disappointment that I cannot “make it” on my own financially. How many times have I wished I would have gone to law school rather than poetry school?

string two sentences together, much less create something beautiful, yet they are rewarded handsomely for their athletic ability while scholars live on government support and are wracked with debt? How many of us have told our parents, “if I just get this degree, publish this book, I’ll get the job,” “I’ll be substantial”? How do we explain having two advanced degrees, two or more poetry collections, a CV a mile long and nothing substantial to show for it? I, for one, continue to live with the endless disappointment that I cannot “make it” on my own financially. How many times have I wished I would have gone to law school rather than poetry school?

Which brings me back to the subject of topics. What is okay for a woman to say? When women write about love, marriage, children, they risk the mortal sin of sentimentality. They are overlooked or discouraged by male gatekeepers. When men write about the same topics, they are applauded for their vulnerability. It feels very wrong at this very moment to lament being poor, for following a passion in my twenties rather than being practical, but it’s even worse for a man to do it. Regardless of the inequality in financial recognition that exists between athletes and intellectuals, or men and women for that matter, what’s admirable about Snodgrass is that he remained true to himself. That’s essentially all anyone, man or woman, can do, as Shakespeare’s been telling us for four hundred years: Write what’s true.

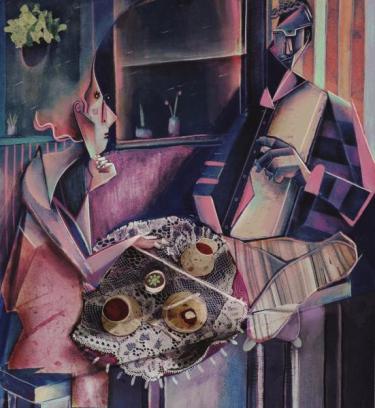

Top illustration by: Mary Ann Smith. Mary Ann Smith came to New York City to attend Parsons School of Design and made it her home. After earning a BFA degree she began illustrating and designing professionally. She has illustrated for magazines, newspapers, the web and book publishers. Her clients include The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, The International Herald Tribune, GQ, BusinessWeek, Security Management Magazine, Bethesda and Arlington Magazines, Penguin Books and Simon & Schuster.She also designs book covers for major and independent publishers. This includes trade, hardcover, print, e-books, fiction and non-fiction titles. Her clients include Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, Hachette Book Group, St Martin's Press, Harlequin, Columbia University Press, Ohio State University Press, Fairwinds Press and Henry Holt.

Bottom illustration by: Kali Gregan. Kali Gregan is an Illustrator from Richmond, VA. She studied Communication Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her work is featured in Latin American Illustration 4, and in galleries and publications around Richmond.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop