On “Missionary" from issue 299.2

It would be the most boring version of the Kama Sutra, abridged for beginners. Overseas evangelists would blush as they walk past it in the aisles of Barnes and Noble. (I kid, I joke.) I wrote “Missionary” in South Dakota in 2011, during what I would later refer to as my “Kerry Fellowship,” on a ranch adjacent to a cattleman named Ted Angel who’d once held his neighbors at gunpoint. I was a summer intern at a wild horse sanctuary, and was initially given lodging on the shores of the Cheyenne River, in one of those silver-tin, hoho-shaped, fifth wheel camping trailers that smelled like cat piss and had no running water. “No toilet? No problem,” I said, understanding very quickly that this was not at all true.

Each morning, I was up with the sunrise, driving a modified pickup truck with a pointed metal rod where the accelerator had once been, and if I sat at the very edge of the seat with foam upholstery missing in chunks, the tip of my toe could accelerate up into the canyons to drop feed in lines like the yellow dashes of a road, onto the prairie for the now mildly-feral horses. When we had to reload the truck at the silos, I had to balance on two empty 5-gallon buckets to reach the release lever, which was really difficult to turn (lady troubles). At the sanctuary, the men insisted women do women’s work: filing paperwork, watering plants, sweeping. I refused, out of principal, mostly, and also because I wanted to get my hands dirty. I was a liberal feminist in one of the most conservative places in America. I tried to prove points: throwing 50 lb bales of hay, weed eating, mucking, hauling lumber. After all, I’d grown up on a farm.

In August, when the air conditioning broke in my tin hoho hut, a ranch hand named Kerry offered a room in his nearby cabin. It was 103 degrees, so I said yes. I had only brought a few books out west with me: Walt Whitman, Frank O’Hara, Michael Cunningham, and a giant volume of Dali paintings. In my free time, I spent a lot of time on the floor drinking tequila and drawing pictures of rhinoceroses. It was 30 miles to the nearest town, partially on dirt roads, so I rarely went out. When the internship was over, I really didn’t have enough money to go anywhere else (poor planning on my part), so I applied for jobs that were two hours away—the closest city to us. I got none of these jobs as a bank teller, gas station attendant, secretary, or waitress, so I stayed at this cabin, writing every morning on a picnic bench overlooking the red-streaked canyons, reading old college textbooks I’d bought at Goodwill and the Army Surplus Store. (I’d found a biography of James Baldwin and A Brief History of Hysterectomies, written in 1952. Score!) I watched toads stalk daddy long legs through the flowerbed of pansies. I wrote.

“This is like a free writing year,” Kerry said, happy to have company. “Stay as long as you want. Stay forever!” I was the only twenty-something woman in the area who had all my teeth. I suppose that was part of the appeal. And I did stay, for six months. I began calling it my “Kerry Fellowship,” having not achieved any of the writing fellowships I applied for. I was able to buy a few books online. I wrote, I cried out of boredom, watched Jersey Shore with Kerry, sent post cards to everyone I knew, hiked, and carried sticks to fight off mountain lions, realizing later that these sticks made me look a lot like a deer. I wrote more, read the books I’d always wanted to, but never had the time. I grew as a reader.

It was nice to have time. My total immersion into this unique cowboy culture created a series of poems that dealt with displacement, gender disparities, and wilderness. Writing “Missionary” was reactionary as much as it was inquisitive. In the end, it was the feelings of loneliness that shaped this poem. It echoes with absence and loss: of rainforest, animals, power, and certain types of closeness—the questioning of what for? Living in South Dakota created a foreigner of me. The distance was important for the writing process. And when the time was right, I moved into the basement of a sandstone building that allegedly once served as Calamity Jane's brothel, and started the long revision process towards the more familiar East.

Christa Romanosky is a Pittsburgh, PA native. Her work has appeared in The Kenyon Review Online, Boston Review, Crazyhorse, Mid-American Review, Colorado Review, and elsewhere. She currently teaches poetry writing in Charlottesville, Virginia. Christa was featured in the Spring 2014 issue of North American Review.

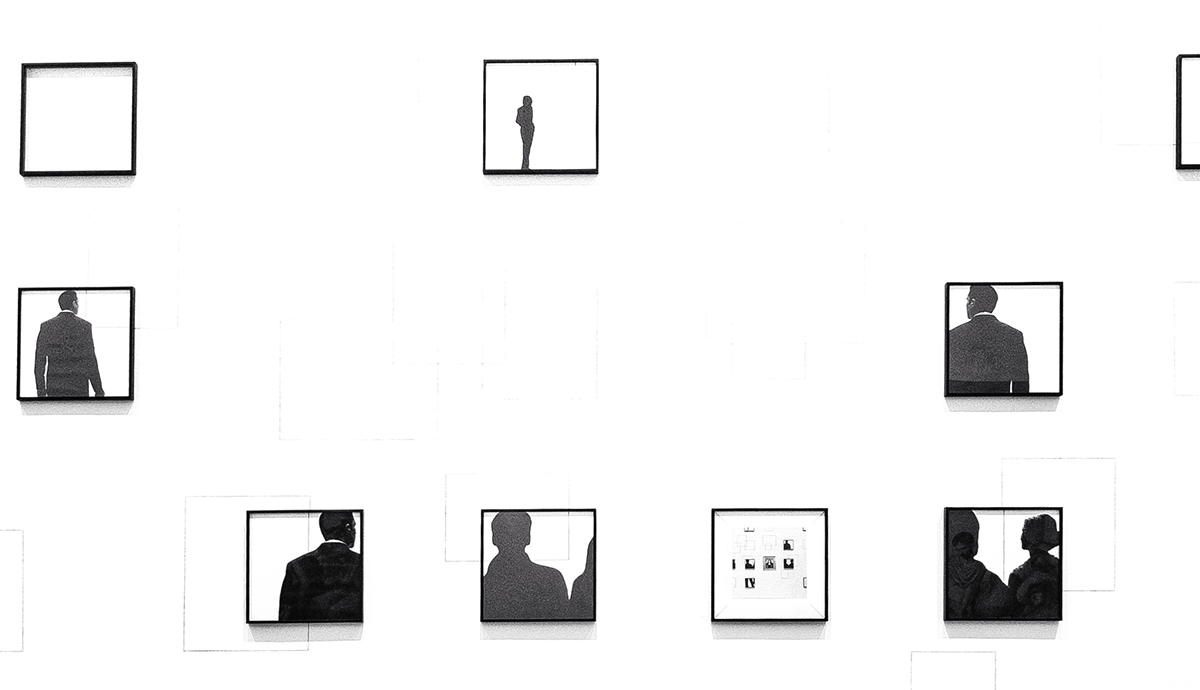

Photo by: Gary Halvorson