On a Secret Language of Women as Fragrance, or Postscript to “A Short Autobiography of Perfume”

If I could sprout wings and fly anywhere in the world, where would I go?

Maybe to an overseas perfumer where I’d try new fragrances all day long, or fly back in time to the earliest history of perfume ~ a narcotic blue lotus ancient Egyptians would hold right to their noses, for instance, or unadulterated rose petals distilled in copper florentines only centuries away from modern laboratories of ethers and esters, and oils such as horseradish, olive, and sesame mixed with a resinous fixative, as described in Jean-Pierre Brun’s “The Production of Perfumes in Antiquity” in The American Journal of Archaeology. “A Short Autobiography of Perfume,” appearing in the Spring 2015 issue of The North American Review, arose from these inklings.

Concurrently, I was teaching Diane Ackerman’s A Natural History of the Senses in a lyric essay workshop where I invited students to write a short exercise inspired by the olfactory sense. Here is an excerpt, quoted from Chapter 1 (“The Body of Memory”) of Tell It Slant: Creating, Refining, and Publishing Creative Nonfiction by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola, one of our required texts: “Which smells in your life are gone for you now? Which ones would you give anything to smell again? Have you ever been ‘ambushed’ by a smell you didn’t expect?”

Laden with vials of perfume, subsequently, I’d fly to a village in the Jiangyong county of Hunan province where Chinese women, for centuries, lovingly hand-stitched books as gifts to their daughters. Sisters and grandmothers, what is the aroma of your memories? Would you teach me a few words of your language? This special language, nüshu 女書, not only existed in written form; as an oral literary tradition, it was sung aloud by memory, too. In exchange for showing me books of nüshu 女書, I’d share the essence of this language in the form of perfume.

Sadly, the last surviving writer of nüshu 女書, Yang Huangyi, passed away in 2004. According to Henry Chu of the Los Angeles Times, “At a time in China when most females were illiterate and considered the property of men, these women turned objects of domestic life into avenues of escape and found solace among ‘sworn sisters’ with whom they communicated in their own language.” As a tribute to nüshu 女書, here is my sister-poem to “A Short Autobiography of Perfume.”

On a Secret Language of Women as Fragrance

If I could, I would bottle nüshu as perfume.

What is the aroma of a secret language written only by women?

How would gynocentric proverbs translate to our daughters

via memory as fragrance or vice versa?

Without vessels, where would we pour

our grievances against the patriarchal order?

On the broom-swept dirt in the village? Dust raised by bicycles?

The threshold of a school we could not cross as girls?

If our language enfleuraged as perfume - no other linguistic traces

aflame - we could revive the chemistries of aroma

without translation, wafting the base notes of female experience

at a draught.

Mexican women create their own paper from scratch using boiled ash, lye, and peeled bark. Brazilian chapbooks or foletos are sold on a string outdoors in folk-art markets. I love hand-stitched books. In Massachusetts, where I spent most of my girlhood, I read about Emily Dickinson’s fascicles and loved her poetry. Nüshu 女書 is unique in Chinese, however, not only in its matrilineal transmission via handwritten journals, but the type of cursive script Hunan women invented. To share their wisdom in a language transmitted only to daughters, the Hunan village women hand-bound their cloth journals and wrote nüshu女書 inside the pages. In other words, without access to formal education, the women developed their own culture of literacy.

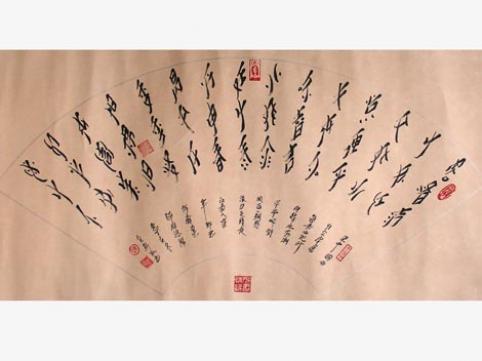

Japanese professor of socio-linguistics, Orie Endo of Bunkyo University, hosts a digital archive of research on nüshu 女書. Not purely derivative of tetragraphs, not quite pictographical nor alphabetical, nüshu 女書 (nü = 女=woman or women; shu = 書=writing or script) was written by ink brush with a thinner, finer hand than the robust strokes of classical calligraphy. Incidentally, the eponymous poem of Kimiko Hahn’s electrifying collection, Mosquito and Ant (W. W. Norton 2000), refers to the culture of nüshu 女書. The fine script was originally compared to the legs of a mosquito or ant, a dismissive observation initially made by patriarchal contemporaries.

Japanese professor of socio-linguistics, Orie Endo of Bunkyo University, hosts a digital archive of research on nüshu 女書. Not purely derivative of tetragraphs, not quite pictographical nor alphabetical, nüshu 女書 (nü = 女=woman or women; shu = 書=writing or script) was written by ink brush with a thinner, finer hand than the robust strokes of classical calligraphy. Incidentally, the eponymous poem of Kimiko Hahn’s electrifying collection, Mosquito and Ant (W. W. Norton 2000), refers to the culture of nüshu 女書. The fine script was originally compared to the legs of a mosquito or ant, a dismissive observation initially made by patriarchal contemporaries.

When I lived in Berkeley during the late Nineties, I’d visit a shop displaying (for sale) reams and rolls of handmade paper from all over the world. Once, I used long sheets of handmade paper ~ turquoise, gold, crimson ~ for a giant accordion chapbook as a part of a family literacy program. The chapbook, like a tall child, stood on the floor to the height of my arms. What if all this paper suspended from the ceiling, layer upon layer of color as self-revelation ~ gave voice (i.e. wings) to the memories of women who made them?

After I moved south of the Bay Area to a coastal mesa in southern California, I would make recycled paper. The year-round sunshine in Orange County is good for shredding old paper, re-soaking it in glue and hot water, then drying the mess with zoysia grass, one-winged samaras, and bougainvillea. In my little art closet, scraps of silk-screened washi mulberry and dyed rice paper sang forth in a range of vivid hues: cerulean, ochre, scarlet, midnight, dove-gray, fuchsia, saffron, or ultramarine. If saffron were a woman, how would she hum in a language of windborne pollen: a diasporic fragrance of this late season?

Summer, summer, summer, I imagine.

Xiatien in Mandarin, the women echo.

. . .

Fragrance of ellipsis in honor of nüshu 女書.

Karen An-hwei Lee is the author of Phyla of Joy (Tupelo 2012), Ardor (Tupelo 2008) and In Medias Res (Sarabande 2004), winner of the Norma Farber First Book Award. Lee also wrote two chapbooks, God’s One Hundred Promises (Swan Scythe 2002) and What the Sea Earns for a Living (Quaci Press 2014). Her book of literary criticism, Anglophone Literatures in the Asian Diaspora: Literary Transnationalism and Translingual Migrations (Cambria, 2013), was selected for the Cambria Sinophone World Series. She earned an M.F.A. from Brown University and Ph.D. in English from the University of California, Berkeley. The recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Grant, she serves as Full Professor of English and Chair at a liberal arts college in greater Los Angeles, where she is also a novice harpist. Lee is a voting member of the National Book Critics Circle.

Top and bottom illustration by Claire Stigliani, a drawer and painter known for her works inspired by paintings, photographs, magazines, posters, YouTube clips, literature, performance, and plays. These works explore the act of watching and being watched and blur fiction with reality. Her recent shows include The Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, The Chazen Museum of Art, Madison, (WI), The Dean Jensen Gallery, Milwaukee, (WI), Russell/Projects, Richmond (VA), and the Jenkins Johnson Gallery (NY). She is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Art in Drawing, Painting, Printmaking and Photography in the School of Art at Carnegie Mellon University.