"Sacral Attachment: India – Guyana – United States"

According to family stories, where we are “from” is a skein of yarn bound tightly around a wooden spool. The yarn is so plentiful that the shape of the skein is no longer oblong but rather more spherical. We are from Chuluota, Florida; from Richmond Hill, New York; Toronto, Canada; Croydon, England; Georgetown, Guyana; New Amsterdam, Guyana; Crabwood Creek, Berbice; Chennai, Tamil Nadu; Barabanki, Uttar Pradesh; Allahabad, UP; Patna, Bihar. After all of the yarn is unraveled, there is no spool. It was only ever a dream, or the legend of a spool. I’ve seen most of these places, but never as an insider, never as someone who belongs in the spaces. My navel string is not tied to these lands.

As someone who is constantly referred to as NRI, American-when-outside-the-States, coolie, and terrorist, where is belonging if not judged relative to where I am presently? Poets and writers like Gaiutra Bahadur, Suzanne Persard, Faizal Deen, and Divya Persaud have all expressed to me the difficulty of not fitting the landscape of American racializations and mediate their own ideas of Asian Americanness.

Gaiutra Bahadur sets our dialogue into motion with her book Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture (University of Chicago) by allowing a subaltern history access to the world of Letters. In her book that straddles the literary and academic spheres she maps the voyage of her ancestor through family myths and ship and governmental records, to show a subjectivity once believed impossible to speak from—that of the Indo-Caribbean woman.

Bahadur writes, asking questions that led her through this history of Sujaria, her great-grandmother,

And if caste didn’t define her, did place? In rural India, navel strings are buried where babies are born, signifying a sacral attachment to that land. Did it grieve Sujaria that she might never return to the earth that held her navel string? Her descendants would continue to bury the umbilical cords of their children, wherever born. They would retain that folk custom, but lose any sense that sacred texts declared the seas would erase their identities (Bahadur 46).

In her accounting, Bahadur lays bare the notion of cross-sea journey as a tabula rasa, an erasing of identity to be renewed through dislocation.

Suzanne Persard insists that she is and is not Asian-American as her family has been outside of Asia for over a century. Persard identifies as part of the South Asian diaspora and considers herself to be part of the Asian diaspora as a trick of linguistics. In Jamaica, she identifies as Indian and not Asian—a category she encountered once coming to the United States. She is at once Jamaican and Indian. She says,

In America, my issue is the boxed identity of the Asian-American that's alienating because it doesn't account for diaspora.

Here, diaspora means Indian communities in the Caribbean, not the children of immigrants from Asia recently landed in the United States. In an interview with the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, Persard reflects on the dislocations and connections she has with India. She says,

As a first generation Indo-Caribbean kid in the US, the language of indentureship entered my vocabulary at an early age. I recognized a relationship to India in a sort of mythological sense: knowing that my roots were from a place that I’d never traveled to, from a culture with which I was connected to but simultaneously excluded from in many ways (Smithsonianapa.org).

India is an ancestor, something distant and dreamlike. It does not exist outside of the imagination or the “vocabulary of indenture.”

Faizal Deen believes he can use the category of Asian-American strategically to create a platform to speak from. And in doing so he creates space for the next voice—others like him. Deen was the first queer Guyanese-North American poet I read, in his book Land Without Chocolate (Wolsak and Wynn Publishers Ltd). Deen writes,

…you see this is what India found we found

this hari that falls out in memory we found all

these pages of monsoon washing all myths away

leaving you open and bare cruel in the eyes of

El Dorado…(“Epilogue” 64).

Evident in his poem is his conflicted relationship with India and also with “El Dorado,” the name given to Guyana in 1598 by Sir Walter Raleigh. Deen excavates the settler colonial violence of the British and shows how its trauma is mapped on the bodies of the formerly colonized and their descendants.

Divya M. Persaud, sees her connection with things South Asian as tenuous, choosing rather, to belong to the world of poetry. What’s expected of her speaker is not what the speaker wants. Persaud writes in her poem “Brown Girl Poetry,” after “[taking beginner’s Hindi three times because / I just plain wasn’t interested.” Persaud’s speaker rather states,

I could have a salwar and a bindi and

they’d cringe when I’d open my mouth

like I was some jungle creature. I used

to practice roaring with my sister.

She writes her poetry as a means of surviving her “failures” of South Asian expectation—that for her, “roaring” is the work of her poem. She is currently sending her work out for consideration and laments the way that publishing in the United States is hard for the invisible, for brown chronically ill women, when according to an article at Publishers Weekly eighty-nine percent of the published works in the US is by white folks. She, instead, chooses to self-publish her volumes of poetry.

My poem “American Guyanese Diwali” is a map to my interior experience of this constant change; Asian American Guyanese Indian Indo—a poetic that maintains any hearkening back to India as an origin place implies stasis via the ethnic construction of “Indian” rather than allowing for the potential for change and creolization that happens in the Caribbean. I hope that the title is somewhat jarring and that reader faces dislocation because hyphenated categories often end with “American,” i.e. Indian-American, Guyanese-American.

For me, Diwali is a festival where we have to clean house. Five days and nights of celebration and vegetarianism. It’s something that I had to excavate; my own family includes Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, and atheists. My parents, converts to Christianity, tried to bury these traditions, but they emerged transformed and inclusive to fit any landscape that they now thrive in that is multireligious and multiethnic and, for me personally, is like Derek Walcott’s vase that is fractured, broken, and pieced together with a stronger love.

According to the “old ways” of Guyana and through mythology, the North-Indian village my grandmother was from, burying the placenta was a connection to the land that we would till. But abroad, this connection is severed with scalpels, having been born in London, England. The afterbirth is tossed into a bin marked BIOHAZARD or sent out to sea on a garbage barge. I hope it’s the latter so my connection remains marine. My connection is to the sea and voyage; to those places where I am “from” and where I cannot “belong.”

Winner of the 2015 AWP Intro Journal Award and the 2014 Intro Prize in Poetry by Four Way Books for his manuscript entitled The Taxidermistʻs Cut (Spring 2016). Rajiv Mohabir received fellowships from Voices of Our Nationʻs Artist foundation, Kundiman, The Home School (where he was the Kundiman Fellow), and the American Institute of Indian Studies language program.

His second manuscript The Cowherd’s Son won the 2015 Kundiman Prize. He was also awarded a 2015 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant for his translation of Lalbihari Sharma’s Holi Songs of Demerara, published originally in 1916.

Winner of the 2014 Academy of American Poet’s Prize for the University of Hawai‘i, his poetry and translations are internationally published or forthcoming from journals such as Guernica, The Collagist, The Journal, Prairie Schooner, Crab Orchard Review, Drunken Boat, small axe, The Asian American Literary Review, Anti-, Great River Review, PANK, and Aufgabe.

Winner of the inaugural chapbook prize by Ghostbird Press for Acoustic Trauma, he is the author of three other multilingual chapbooks: Thunder in the Courtyard, A Veil You’ll Cast Aside, na mash me bone, and na bad-eye me .

Rajiv holds a BA from the University of Florida in religious studies, an MSEd in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages from Long Island University, Brooklyn when he was a New York City Teaching Fellow. He received his MFA in poetry and literary translation from Queens College, CUNY where he was Editor in Chief of Ozone Park Literary Journal. While in New York working as a public school teacher, Rajiv also produced the nationally broadcast radio show KAVIhouse on JusPunjabi (2012-2013). Currently a PhD candidate in the Department of English at the University of Hawai’i, he writes about colonial-era anti sodomy laws, plastic, and humpback whales.

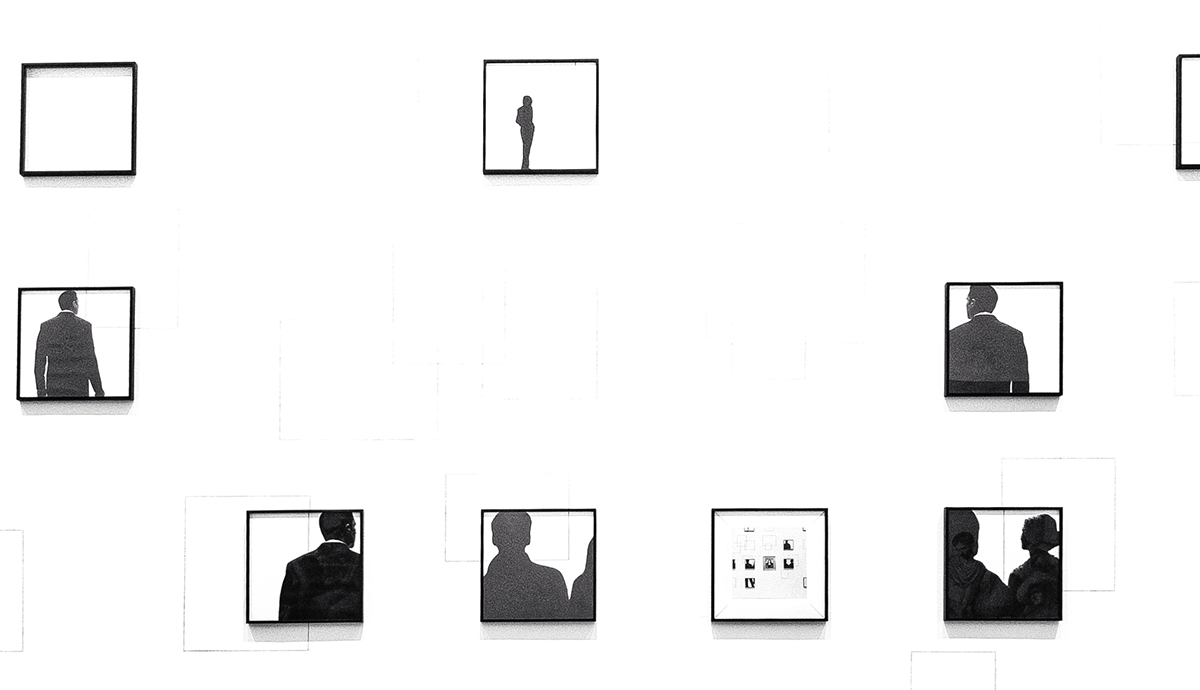

Illustration by Kali Gregan. Kali Gregan is an illustrator based in Richmond, Virginia who finds inspiration in Cubism and collage.