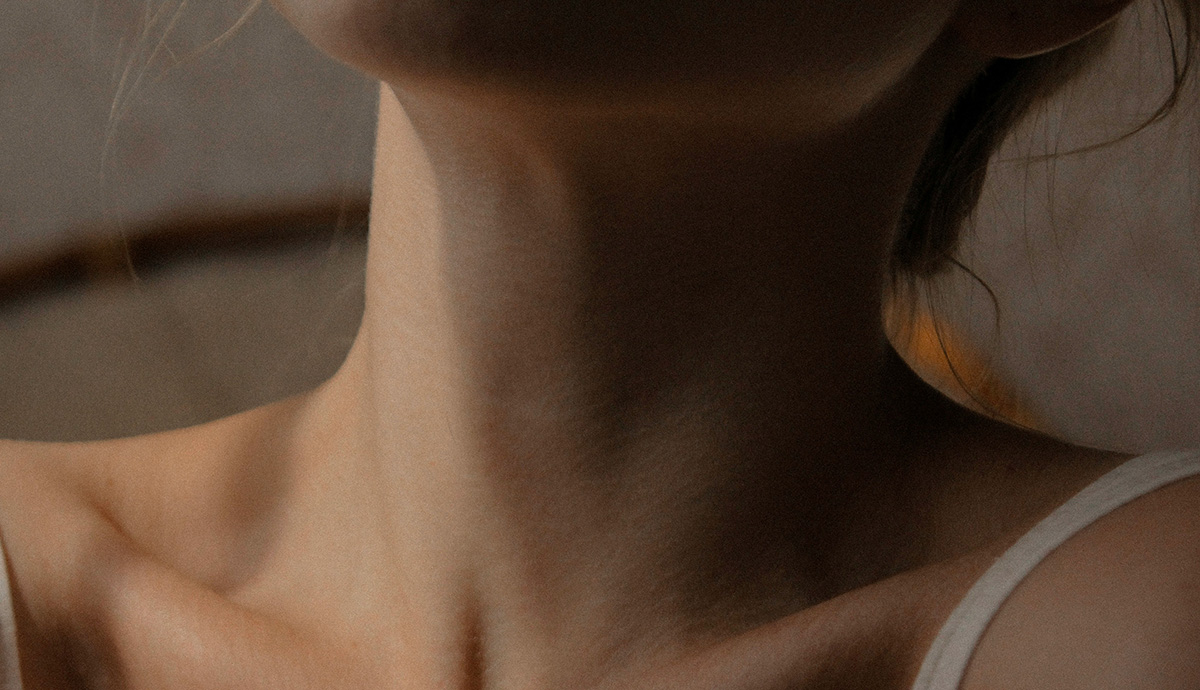

Tear the Skin

This is the pandemic where I patrol the hairs growing on my neck. I think about the terrain below my chin more than any part of my body. What a waste, all this self-surveillance—I can’t help it. Tonight, while my toddler buries bottles of soap in the bath, I am his lifeguard. My back is to him and I watch him in the mirror. I enlist grocery store tweezers and hunt for coarse hairs to pull. He sings a song about how shooting stars are meteors. I tear the skin above my pulse.

“You are bleeding,” my child says, and I am.

I dab a scrap of toilet paper to my skin and it stays there.

It is my turn to put him to bed. My child is never cold at night, not even now, when it is January in Milwaukee and Lake Michigan has frozen along the beach in sheets of ice that the waves fracture into colliding planes. Naked except for a diaper, he sits in my lap in the rocking chair that came from my grandmother's house. Metal has emerged from the back and it scores the wood closet door as we rock back and forth. I open a book about a lighthouse and his hand roams to my throat, finding the rough skin that I try to transform into something new. Whenever he gets tired or wants comfort, his hand drifts to the part of my neck where the hair I wish would disappear grows and grows. He's had this habit since he was an infant on my chest, skull open at the soft spot. Now he has multiplied in size, grown language, moved on from the old beds, bloomed a head too wide for the old sunhat. I tell him about ocean currents in Nova Scotia and the lighthouse on the page gets a new keeper. His fingers go still on my throat, like he is looking for a pulse. That’s how I know we are close now. This is how he self-soothes. The seasons are changing around the lighthouse. Whales head south and icebergs float north. The Northern lights blaze green in the night sky. Soon he will be snoring.

•

I touch that spot of my neck too, compulsively searching for hairs that have grown too coarse or too dark. When I think, when I write, when I watch TV. My fingers migrate to the scar on my chin, that time stamp left by a long-ago fall off a metal wagon when I was the same age as my child, plummeting face first into a sidewalk, and busting open the skin in a seam where now three hairs grow like filament. My mom made plans for a substitute to teach her class and stayed home with me, replacing the gauze. You know how faces bleed and bleed. From my chin my hand travels on a route south, to the constellation of hair changing texture as I age. Over Christmas I tried to let the patch of hair on my neck grow. My mom mistook it for a smudge of dirt, trying to wipe it away.

•

He raises his head then lowers it, his fingers crumbling into half a ball. I scratch the closet door with my rocking and strategize new approaches to my relationship with this hair. I will embrace it. I will let it grow, let it age, let it bleach in the sun, turn soft and fine like a dandelion stem, like the light fur that once shone iridescent on his infant neck, as I sat in the glow of a night light patting his back and checked to see that he was still breathing, inhaling him. I am falling asleep, too. I breathe and his head rises on my chest.

•

My mom has the same habit. Her freckled hands travel the same route across her neck. It took me thirty years to notice we shared this gesture. On long car rides she will drive with two fingers against her cheek, two under her chin, forming a letter L of a hand angled so she can brush her neck with her thumb. Now I know that she too searches herself for signs of something that she forgot.

I’m sorry to say it, she said in those first weeks of the pandemic, when we shared a house with one bathroom and tweezed side by side in the bathroom mirror. You got those from me. We pulled our skin to the mirror until we could see the pores.

•

It is time to leave this dark room, with fake stars orbiting the ceiling. A speaker in the shape of an owl plays the sound of waves crashing. I lift my child carefully and move toward the bed. I never know when he is asleep or just still. His head shoots up and his hand curls on my throat. I have been caught trying to leave.

“Does it hurt? Here?” He presses his fingers to my beating pulse.

I am deciding on my answer when he drools on my chest. The end has come. His breathing is slow like waves hitting ice. A letter L of a hand rests on my neck.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop