What so Proudly?

1.

It’s a stupid joke. A cruel joke. A dad joke made brutal in the mouth of my grandfather. It is part of a whole subgenre of jokes specific to the Second World War. Who knows if it actually happened or if people just remembered it from the movies.

Sometimes the infantry advanced so fast, the lines were so confused, and the terrain was so difficult that soldiers had no idea where they were or what units they were fighting alongside. The Nazis had elite infiltration teams trained in American English and American culture who impersonated American GIs down to every detail of their uniforms. All kinds of passwords and special tests were devised. Questions about baseball or references to jazz songs. Even the most basic things.

So this guy comes to the checkpoint in his combat ODs. Says he’s with such-and-such unit, got separated from them, is trying to find his way back. The sentries say they’ve never heard of that unit. He says it’s attached to the whateverth.

One of the sentries says, “Oh yeah, they’re about ten miles up the road. Geez, buddy, you’re a long way off from where you’re s’pposed to be.”

“Yeah, well, Sarge is gonna have my ass when I get there, but I gotta catch up.”

“Sure, buddy. Just sing the Star-Spangled Banner.”

“The Star-Spangled Banner?”

“Yeah. Like at the ballgame. Sing it.”

This guy sings the National Anthem better than any of the sentries have ever heard it sung before. He sings it with the passion of an opera star singing for his life. Everybody within earshot is misty-eyed as the man belts out the dramatic crescendo. For a moment they are lost in patriotic reflection.

When he starts singing the second verse, they shoot him.

2.

My mother’s father was a bombardier in the 57th Bomb Wing of the US Army Air Forces, which operated out of Corsica in the last two years of the war. That unit was made famous by Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22, which satirized the high command’s ability to extend deployments indefinitely. Supposedly, though, any member of a combat crew who completed twenty-five missions could go home and serve the rest of the war as a flight instructor.

My grandfather’s obituary notes that he flew twenty-six missions as a radio operator and gunner. True, he served in those roles, but he was usually a bombardier. I have seen the flight manifests. I have not seen any evidence of what he did on that final mission after he completed twenty-five.

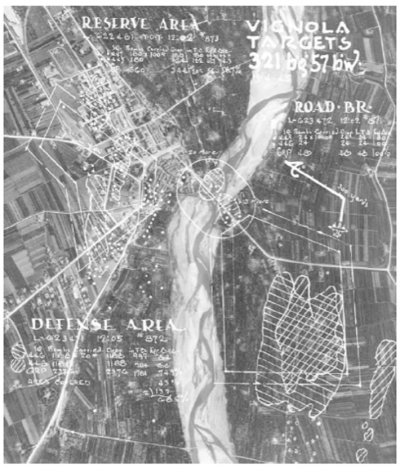

But there is a story that, in addition to being a radio operator, gunner, and bombardier, my grandfather was also an aerial photographer. There were, of course, official USAAF photographic units, but most of the confirmation photos of bombing runs done by medium bombers were less formal than that. A lot of them look like somebody just stuck a camera out the waist gunner port and snapped a shot or two.

![446th Bomb Squad, Ops Order 872: “Vignola Def. Area” (Apr. 19, 1945) Boots [Tail #32]: Sgt. Leo F. Lohrman (engineer), S/Sgt. Jesse A. Sanders, Jr. (radio) 57th Bomb Wing Association, 321st Bomb Group History (April 1945): 221, 229.](/sites/default/files/resize/picture1-400x361.png)

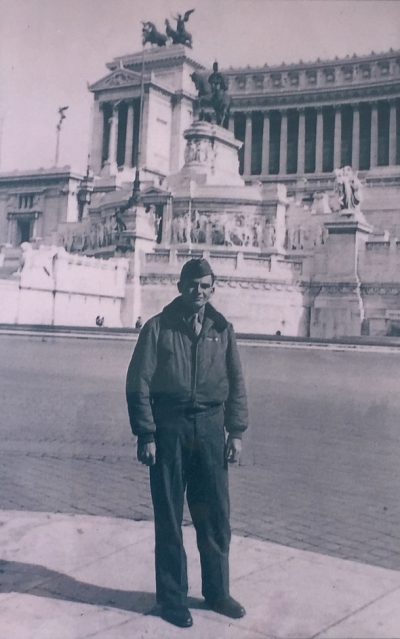

My grandfather was a camera enthusiast by the standards of 1945. That basically meant he had a camera and he took photos whenever there was something worth photographing. There is a photo of him standing in front of the Altare della Patria at the center of Rome after that city had been taken. Nobody else is in the shot. All the Italians must have been hiding indoors.

3.

If you want a joke to stay funny, you should never explain it. I want to, though. It’s tempting to see nothing but stereotype in that joke. You know an American by his ignorance and a German by his compulsion to do everything only too well. But could there be something in the later verses of the Anthem that a Nazi would actually want to sing?

Francis Scott Key famously wrote the lyrics to the Star-Spangled Banner after witnessing the bombardment of Fort McHenry from the Baltimore Harbor, so it was always a war song, even if the tune was borrowed from a drinking song. Washington had already been burned by British troops, and the federal government had retreated into Maryland. Key’s most controversial lyrics are in the third verse, where he condemns “the hireling and slave” to death—a reference to the British Army’s recruitment of escaped former slaves to fight the United States.

It wasn’t the first time the British Army had promised freedom to subjugated peoples willing to take up arms against the States, and Key’s lyric combines an automatic racism with a disdain for mercenary soldiers that was carried over from the Revolutionary War. Indeed, white Southerners’ perspectives on the Emancipation Proclamation during the Civil War were likely shaded by this memory. The unwillingness of Confederate armies to grant quarter to black Union soldiers during that war was obviously sheer racism, but that racism was partly based on this understanding that African-Americans were, by definition, exempt from citizenship and thus as soldiers were merely mercenary outlaws.

The German Army had a similar attitude toward French and British colonial troops during the First World War and frequently tortured Afro-French POWs. Similar atrocities obviously persisted into the Second World War. The Third Reich only made the racist underpinnings of nationalism more explicit than other empires built on white supremacy. Intentionally copying legal and social approaches from the United States, Nazi Germany redefined citizenship and even humanity in a way that followed directly from the worldview of men like Francis Scott Key.

You can imagine the other things they did. The world had been ending for a long time by then.

4.

The story goes that one day, as my grandfather’s waiting to ship back and hoping they don’t send him to Japan, the Colonel sends for him.

“Hanley, aren’t you the kid who’s always taking those photographs?”

He was twenty-four years old and had managed to get halfway through the SUNY School of Forestry at Syracuse before he had been drafted.

The Colonel took him to the General. The General took him to a lieutenant he’d never seen before who gave him a camera and put him on an airplane. Then the Colonel and the Lieutenant and three sergeants and two guys he had never seen before—either from OWI or OSS—flew for several hours from Rome to somewhere over Poland. They flew all the way to the other front. As they flew over a prison camp, he was told to take photographs.

It was Auschwitz. Believe it or don’t. This story claims my grandfather took the official US Army aerial surveillance photographs of the Soviet liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp. The Red Army was in full retaliation against the nation with which they had fought the biggest and most brutal war in history. They were shooting the guards, of course. When the US Army liberated death camps, they sometimes marched local civilians through and forced them to confront the horrors they claimed to know nothing about. The Soviets were more likely to just shoot everyone. This was an army of soldiers who had been starving their whole lives and had been fighting Nazis for four years. I’m sure they shot a lot of the prisoners too. You can imagine the other things they did. The world had been ending for a long time by then.

5.

The Star-Spangled Banner is notoriously difficult to sing, and this might have been why the tune was originally popular as a drinking song before Francis Scott Key wrote his lyrics. If you want to have any hope of singing it correctly, start as low as possible. “Say” is the lowest note of the song, and if you don’t have an incredible range, it should be the lowest note your voice can manage. This is the only way to ensure you can hit the high part of “the rockets’ red glare” with anything better than a squeak.

Over the years, some have said the Star-Spangled Banner is undemocratic as a national anthem simply because it is so difficult to sing. As more people have become aware of the content of its later verses, the idea of changing the anthem has recently edged into mainstream discourse. Yet, this strange and embarrassing song fascinates me. Its weird peaks and pauses are certainly very different from most national anthems, but they also are exactly the elements that make it appealing. The UK sings to its sovereign head of state; France sings a revolutionary marching song; some nations sing old folk songs or odes to the beauty of their country. To me these all inevitably sound like one monotonous verse after the next. But the first verse of the Star-Spangled Banner dramatically builds to its crescendo and concludes definitively on the adjective that it claims as the bare requirement for any soldier, citizen, and free person in a world of bombs and rockets. It is true in spite of itself. Even two months ago when a group of San Franciscans spray-painted “slave owner” on Francis Scott Key’s statue and tore it down, they knew they needed to be brave to be free.

6.

In 1980, my grandfather traveled to the USSR representing the Hardwood Plywood Manufacturers Association. Walking around Moscow, he was disturbed by the number of children begging for candy and cigarettes. Government officials brought him on tours of furniture factories, demonstrating their plywood manufacturing techniques and extolling the efficiency of state-managed production systems. My grandfather made phone calls to Vermont and Quebec several times a day. These bookkeeping calls were so technical that they consisted almost entirely of numbers. They must have sounded incredibly suspicious, and he was sure someone was listening in. Eventually, he was told he would not be allowed to make any more international phone calls. By the time he got to Leningrad, he was sure he was being tailed.

After checking into the hotel, he left everything but his wallet and passport behind and got on a train to the airport. The travel agent there gave him every excuse in the world for why it would be impossible to leave the country that day. Enraged, my grandfather slammed his American Express card down on the counter and demanded to get on the next flight out.

That flight from Leningrad to Copenhagen was the most expensive ticket he ever bought.

Several months later, when he was back home in Newport, Vermont, he received a letter from the Soviet consulate in Montreal saying that they had his briefcase and suitcase. A consular agent drove the two hours to Newport and returned them. He even apologized for the whole situation in Leningrad.

The man tried to laugh it off. Someone had clearly gone through the briefcase, which was filled with papers listing prices, exchange rates, inventory, and other boring information. The agent shrugged as though this were the kind of scrutiny anyone would expect of a government apparatus.

“It is too bad,” he said, “but not so bad for you. After all, Sergeant Hanley, you always did like to take photographs.”

7.

The Star-Spangled Banner was a popular, if unofficial, patriotic anthem for decades before it was adopted as the official National Anthem. Of course, the words had been around since 1814, but the song only really gained popularity among ordinary Americans with the rise of organized team sports. It was a song that started off baseball games long before it was used by the actual US government.

For a long time, it was the only explicit invocation of nationalism at baseball games. Growing up outside Baltimore, I remember being surprised to discover that, in other parts of the country, people do not loudly yell “O!” just before the verse’s climactic question. I remember at one point being reprimanded by a teacher who told us we should save our cheering for the game and show respect for the Anthem first. Others have commented on the irony that the city whose defense inspired the song would have a tradition of yelling over it.

Over the years, I have noticed that the Baltimore Orioles’ “O” cheer has drifted a bit and become more subdued. The shout I remember from my youth as a raucous interruption of the Anthem’s moment of silent contemplation has now become part of its ultimate question. It was once sung like this:

…gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.

…O!!!

…Oh say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

…o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

Now people usually sing: “Oh say does that star-spangled banner yet wave…”

Unlike that “O!” which always seemed intentionally silly and low-class, “Oh say” merely adheres to tradition. It does not interrupt the Anthem but instead adds to it. There is fear in that “Oh” of sounding unpatriotic; it is not a celebration but an obligatory effort to continue the tradition without offending an even more obligatory nationalism.

I am not sure when this shift occurred, and I cannot even be certain that my memory correctly represents it, but I suspect that “O!” changed to “Oh” in 2001. After September 11, Major League Baseball also began to include “God Bless America” as part of the seventh-inning stretch, and both the MLB and NFL incorporated significantly more nationalist and military iconography into their events.

8.

I used to carry my Selective Service card in my wallet. I joked this was “in case a war breaks out.” My first day of college was September 11, 2001.

My grandparents had five children, including two sons who were of military age during the Vietnam War. My grandfather was generally known for his left-leaning political outlook and later in his life would occasionally joke about how his then-Congressman Bernie Sanders was “a little too conservative” for his taste. Living only a few miles from the Canadian border and having contacts through the import business, my grandfather supposedly had an agreement with a family of Québequois farmers and woodsmen to shelter one or both of his sons if it was necessary for them to hide from the draft board.

In the nineties, my mother would tell me this story as a way of signaling our family’s political commitments and reassuring me that I would not need to fight in the kind of war that had killed so many of her friends. I was never quite sure what to make of that. I have a skepticism of war that verges on automatic opposition, but I also know that leaving others to fight wars is not really a responsible solution.

I used to carry my Selective Service card in my wallet. I joked this was “in case a war breaks out.” My first day of college was September 11, 2001. We saw the news footage in the Wal-Mart as we were picking up a few last items. I remember looking my mom in the face and angrily yelling, “Where the fuck is the CIA?” It was the first time I ever cursed at her.

I had thought of government agencies as shadowy and dangerous networks for several years by then. Even in those years before the USA PATRIOT Act, I had assumed CIA and FBI kept an eye on everything, even in the worst way, and I was shocked that they had not.

9.

In the first chapter of his novel Breakfast of Champions, Kurt Vonnegut critiques a number of aspects of American history and culture with his characteristically insouciant humor. He mocks the National Anthem for being a series of long, absurd questions. I had never noticed this until I read that novel in college. The Star-Spangled Banner really is little more than one question after the next.

Can you see the flag? Remember the last time we saw it? Remember what it looked like during that crazy battle? Remember how we stared at it? Is the flag still up?

For a nation founded in part by literal iconoclasts, it is a bit odd for the United States’ National Anthem to be about staring at a symbol, but that is also what makes it a perfectly nationalist hymn. Even “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”—certainly an ideologically superior version of jingoism, and one that enjoyed well-deserved prominence as an unofficial anthem at the end of the Civil War—is entirely too ornate and abstract for American tastes.

10.

The B-25s flown by the 57th Bomb Wing were called medium bombers. These days, we would probably use the term “precision bombing” to describe their missions because that sounds clean and respectable. True, most of their missions involved knocking out bridges and rail yards, but others included area bombing.

Some of this would be done with high explosive, but missions against marshaling yards would often be done with fragmentation payloads or white phosphorous. This is a fancy way of saying that they would drop shrapnel and firebombs on enemy troops. Also, because humans are not perfect, sometimes these would fall on nearby civilians.

None of this is surprising. And of course there are many far worse examples of “strategic” attacks on cities, especially near the end of the war. But it’s too easy to say, “My grandfather didn’t do that kind of bombing.” I have seen the mission reports. I have seen the photos scratched over with white crosshatches and scribbled blobs showing where the bombs were supposed to fall and where they “trailed into the town.”

11.

11.

There’s a fine line between, “How dare you suggest our country isn’t perfect?” and, “How dare our country not be perfect yet?”

On a few occasions in high school I remember choosing not to stand for the National Anthem. These moments of protest represented general objections to nationalism and American military power rather than outrage at any specific event or policy. My mind wasn’t so concerned with detail at the time, but the flag and the Anthem stand for our whole history, and I had a broad sense of its absurdity and injustice even then.

The United States of America is a nation founded on ideas and ideals. Often that means we can’t live up to them. Particularly among intellectuals and radicals, it’s easy for us to list the ways that the USA isn’t what we expect it to be. This is one of many forms of American exceptionalism.

When I was working on my PhD in American Studies, my closest friend was a Pakistani-American who had lived most of his life in Mississippi and in many ways understood more about the United States than I did. His immigrant’s perspective was sometimes lost on others in our program. When people would object to this or that government policy or make bold statements like, “I won’t stand for the National Anthem until…” it always seemed to him that we were demanding our nation be perfect.

We’ve spent whole careers describing the way it isn’t, and yet the fact that we do that—not only that we have the freedom to do it but that we consider it our duty to do that—is the whole point. My friend would often remind me that, in most other countries, studying “history” means telling stories about how great your country is. There are no complaints about revisionism or political correctness or judging historical figures by the standards of their times. Those things just aren’t debated.

The United States isn’t exceptional in its virtue or even in its willingness to allow such debates. But we may be exceptional in our assumption that we could somehow be perfect. That utopian dream can be both a fantastic motivation and an unending form of self-flagellation.

There’s a fine line between, “How dare you suggest our country isn’t perfect?” and, “How dare our country not be perfect yet?” That sentiment is baked into the Constitution’s effort “to form a more perfect union.”

12.

In 1995 the National Air and Space Museum was set to exhibit the Enola Gay as part of a comprehensive consideration of strategic bombing and the end of the Second World War. Ultimately veterans’ groups and conservative interests lobbied for edits and revisions to the proposal that resulted in the concept being withdrawn entirely and replaced with a neutral presentation of the aircraft itself and reflections of the flight crew.

I remember a heated argument at the dinner table between my sister and my grandfather that Thanksgiving. My sister had commented that it was obviously cruel to have dropped the Bomb and dropping two Bombs was unnecessary and shameful. My grandfather angrily exclaimed, “I’m glad that they dropped the Bombs, and if they’d’ve had more of ’em, I’d’ve been happy for them to drop those too!”

Like almost every other American who fought in the Second World War, my grandfather was convinced that, if Japan had not been completely overwhelmed by the horrific technological catastrophe of the Atomic Bombs, he himself would have been in the invasion force.

I have seen the files. I know he was training to strafe beaches.

Like many of my generation, my sister could not imagine a world in which the USA fought a war where it didn’t have a free hand to make decisions about the time, place, and manner to fight.

13.

On occasion, my wife has caught me whistling the Star-Spangled Banner and glared at me like I’m an idiot. Sure, it’s absurd to imagine somebody going through their life with the National Anthem playing in their head. I don’t even consider myself patriotic. I honestly think nationalism is the worst ideology that anybody has ever fallen for. It is the epitome of all xenophobia and hate. Racists and religious extremists are just nationalists with specifically worse ideas about who should be in their nation.

It’s in the song. It all boils down to that: Where’s our flag? Can you see it? Anyone who goes against it ought to die. That flag is for us, not them. Is it still there?

I’d prefer a world without any national anthems—without nations or borders or money or any of these things we use to tell each other we are better than each other. But that isn’t our world. If I am in this world, and I was born in this country, I am happy to have the Star-Spangled Banner for this nation I love and hate.

And if I’m not exactly happy about it, then at least I see it as appropriate.

When I was seventeen, I tried out for a school musical, and not knowing any other song to sing that wasn’t punk rock, I launched into the Anthem. I couldn’t get to the end without cracking my voice, downshifting register, and bursting into tears, but I pushed through, and I got the stupid bit chorus part out of sheer idiotic stubbornness.

That night, I was pulled into the back room of a record store and accused of shoplifting CDs. I cried again as I emptied my pockets. I had everything but CDs in them.

This is our nation. It is a nation of impossible songs to sing, of inept surveillance, of precocious schoolboys trying too hard and rebelling automatically. It is a nation summed up by a half-racist song, half-known and half-sung, blared out in stadiums paid for with taxes so that rich men can get richer as we watch young men bash each others’ brains to mush.

You don’t need to stand. You don’t need to sing. It will all happen without you.

If you’re lucky enough to be the one who sings the song for everyone else, feel free to add all the extra notes you want.

People might shout in the middle of it. People might yell at each other to shut up and take their hats off. People might be chugging beers and farting.

Meanwhile millions are locked in concrete rooms and cages.

It’s just a bunch of questions about a symbol we’re all staring at.

What does it mean? Is it still there?

With the exception of the photograph of my grandfather in Rome and the header images by Casey Horner, images in this piece are creditable to the US Army Air Forces, obtained by the 57th Bomb Wing Association via Freedom of Information Act request. Further information is available on the 57th Bomb Wing Association website.

Recommended

Encounter

Schizophrenic Sedona

Recense (realized)