Vegetarian

Humanity's true moral test, its fundamental test, consists of its attitude towards those who are at its mercy: animals.

— Milan Kundera

My father was a vegetarian.

So what? you might shrug. These days lots of fathers are.

But this was different. This was the ’50s and ’60s in a farming community outside of Ames, Iowa. My father was undoubtedly the only vegetarian in our school district. Let’s also say he was a conspicuous vegetarian. Six-foot-four, he towered over people and was thin as a rail. I didn’t think about it then, but his position as manager of Napier’s co-op grain elevator selling feed and supplies for raising livestock must have challenged his vegetarian principles. After all, those animals were bound for slaughter.

I can still remember the smell of the co-op’s big feed room. If I walked into that storeroom tomorrow, the smell would take me back to my childhood—the wood floor oily and dark with years of muddy boots, feed sacks piled over our heads. My brother and I would climb on the burlap bags and hang out there, waiting for our father to get off work on Saturday at noon. Seemingly trapped, sparrows looped and bashed about the rafters, until, seeing the square of world beyond the opened sliding doors, they’d make a break. Rat poison traps were tucked into corners and crevices to trick those rogues into a painful death.

Farmers arrived at the front office where my father waited on them from behind a tall counter. They ordered and paid for feed, then pulled their pickups around to the feed room’s dock. Dad was often the only one working on Saturday morning, so he’d meet them at the sliding door to help load.

With the doors open, my brother and I would sit on the piles of feed sacks and look out over our small town. What you saw out there depended on what you wanted or were trained to see. The system of industrialized agriculture coming into existence through the efforts of people like my father was slowly transforming the landscape. We didn’t question these changes. The system was a given, much as it was a given that we lived in Iowa, and it was surely the best state. The state song, which we learned in school, celebrated Iowa as a land of proud farmers.

We are from Iowa, Iowa.

Best state in the land.

Joy on every hand.

We are from Iowa, Iowa.

Yes, that’s where the tall corn grows.

•

In class, we’d yell the word that’s and pump our arm to emphasize how much we felt this pride. Even in grade school, we were happy hucksters for our state.

Our small community was proud of the part we played in the system established to move farm products from the farms to the tables in the towns and cities like Chicago and all the way back East. In the Iowa of my childhood, the system’s tentacles reached everywhere, even touching the small farms that dotted our landscape in the early ’60s before larger farms became the norm.

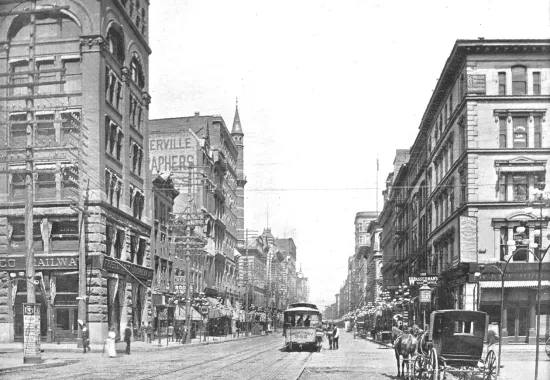

The origin of this changing landscape lay in the westward settlement of our country, in the railroads, and in the parceling of the prairie through land claims in the nineteenth century. Manifest destiny envisioned small farmers taming the land and making it productive. When we admired the sun setting over the fields, the history of the system is what we were seeing, even down to chasing the last Native Americans out of our way in the so-called Black Hawk War that securely opened Iowa for settling. Through those sliding doors, my brother and I viewed a landscape shaped by that history.

The fields of grain fed the animals that were shipped and slaughtered, and then became the hamburger my mother purchased at the Hy-Vee grocery store in Ames. She fed that hamburger to her four sons on Thursdays when the rest of us, but not my father, hungrily ate meat. We normally didn’t eat patties but had it in a manner we called a Maid-Rite. We argued about which condiments made the best hamburger—pickles, mustard, tomato, and lettuce—but at the base was always ketchup, blood red and sweet.

My parents didn’t slaughter their own animals as previous generations had done. As we marched from the ’50s to the ’60s, the animal production system protected consumers from that gruesome process. I’m quite sure my four grandparents killed animals raised for their table, and my great-grandparents thought of butchering as a necessary skill. What was better—to eat an animal you raised and perhaps had some attachment to or to eat meat produced anonymously by the production system? The former was at least honest. It put the knife in your own hand. But the latter has been the basis of our lives for quite some time. Even today much of the grain from those large fields in Iowa is there primarily to grow feed for livestock now finished in large foul-smelling feedlots before being slaughtered. The truth is those slaughterhouses were huge vortexes that drew thousands and thousands of terrified animals every day into their maws and spit them out into all the different cuts we purchased, wrapped in plastic under the lights of the grocery display.

Yet—and here’s the conundrum—I’m not certain my vegetarian father felt compromised. A good soldier in the agricultural revolution, he was convinced that scientific farming practices coming out of universities like Iowa State in Ames made our agriculture exceptional—one to be emulated if the world’s hungry were to be fed. This agriculture was increasingly characterized by tilling more and more acreage with applications of fertilizer, pesticides, and herbicides—with animals moved off pastures into feedlots. He wasn’t the only one who bought into this. If the world farmed like we did in Iowa, there would be no hunger—that was the assumption. It was the green revolution. We didn’t know until later the cost in terms of soil loss, water degradation, and destruction of the environment.

Surely, Gandhi, my father’s hero when he was a pacifist in World War II and went to prison for refusing to register for the draft, would have condemned the system that led to so many animals’ industrialized death. A lifelong vegetarian, he might have looked askance even at our 4-H club as a program to desensitize kids from their natural affinity with animals. Most kids joined 4-H at the time with the goal in mind of raising an animal for the county fair, and if they were lucky in the judging, showing them at the state fair in Des Moines.

One of my friends cried at our county fair when the calf he’d raised that year was sold at the auction that always took place on the last day. I stood with him afterwards in the midway sawdust while he wept. He’d spent the year specially tending his calf, feeding and grooming it, readying it for the fair, surely forming a trusting relationship. Now, his calf was being pushed through a chute toward a truck that would take it away. It must have been terrifying for the calf. Because my friend’s father was a loyal member of the co-op, my father had bought the calf on behalf of the co-op and immediately turned around and sold it to a processor. People were sympathetic about the tears, but there were knowing smiles too. This was a common story, a rite of passage. He’d get over it. He’d get with the program soon enough

Our alienation from animals is just a symptom of a deeper alienation from ourselves.

Despite my father’s vegetarianism, animal husbandry came to our home as well. My father helped my brother Tim construct a pigpen behind our garage where one Saturday he unloaded a Hampshire gilt they’d purchased at auction using “sow bucks” given to my brother by a farmer friend. Sow bucks were points earned on the purchase of feed that could later be used by kids to obtain their own animals to raise.

Tim named his pig Beauregard. She was fed both feed from the co-op and our table scraps. The best outcome for Beauregard was to become a brood sow, regularly bred for her young to enter the meat industry. And indeed, the little pigs that came after Beauregard was bred were sold to a nearby farm family who planned to grow them out for later sale and slaughter. The farmer arrived in his pick-up, and my brother and I scurried around the pen grabbing the piglets by their hind legs to be lifted squealing over the fence and into the back of the pick-up. Beauregard watched the process through stoic eyes.

In prison in Petersburg, Virginia, for his pacifism during World War II, my father objected to working in the prison slaughterhouse and was accommodated by being moved to other work. Years later, married now to an Iowa farmer’s daughter and with four hungry kids, but still a vegetarian, he chose the job in Napier, Iowa, because our community’s grain elevator was part of the rural cooperative movement, something he believed in. The co-op served the farmers in the community who owned it.

But our relationships with animals that provided us sustenance from time immemorial had changed and become industrialized. Animals were now commodities. In the co-op’s office, my father tuned to WOI in Ames every day for the farm report that included the daily price for pork bellies, as if pork bellies just came that way. Given his pacifist and vegetarian views, did he see a karmic cost?

I’m not excusing myself. I lustily ate my hamburger but was squeamish about killing animals myself. Sometimes visiting the families of classmates on their farms, I felt like a sissy. Like my best friend from grade school, I enthusiastically began raising rabbits based on the principles outlined in a pamphlet called “Raising Rabbits for Pleasure and Profit.” My friend planned for profit, too, and had hand-lettered a sign that gave two prices for his rabbits, one live and the other dressed. Dressed, of course, meant that someone would have to dispatch the rabbit and skin it out. I’m not sure he ever had any takers, and like me, owning rabbits just meant a need for more cages to accommodate my exploding rabbit population.

Later, tired of the daily chores, I sold my rabbits off, the last and most cherished one being my first: a big, pink-eyed New Zealand doe named Ruby. She went to Fats Wiese who owned a ramshackle house with various animals he was raising in equally ramshackle outbuildings at the edge of town. He promised that Ruby wouldn’t be killed. I chose to ignore the facts in front of my face and believed him.

One day my oldest brother Chris declared himself a vegetarian, something we meat-eaters looked on with considerable doubt. On Thursdays or during our Sunday pot roast or Thanksgiving turkey, he and my father would eat their protein substitute, sometimes cottage cheese or scrambled eggs, always for Chris topped by the ubiquitous ketchup. One time a cousin, my brother, and I egged Chris on until he took a bite of a hot dog that he promptly threw up. We didn’t laugh. The vomit only proved that Dad’s morality was now deep in his psyche. Chris raised no animals for 4-H, but instead worked in my mother’s garden growing vegetables that he selected in August to show at the fair. School lunches must have been a trial for him, and the teachers in our small school district surely found him odd. Chris would have been a strange guest for meals at his friends’ houses.

Maybe a Greek chorus of vegetarians would protest that my father should have had none of it. They would chide him for the contradiction, arguing his vegetarianism was just a private purity, a way to maintain his spiritual superiority amidst the slaughter. But my father seemed inured to the contradiction between his vegetarianism and what was going on around him. If he saw the incongruity or even suffered from it, he never let on. He rose early every day, dressed in gray work pants and shirt, and walked the short distance from our house to the elevator where the co-op did its small share to make us proud Iowans.

Yet vegetarianism seemed part and parcel to my father’s pacifist stance, and that he linked vegetarianism with pacifism is no wild leap. Conscious life is conscious life, whether human or animal, and we know now what we all ignored back in the ’60s—the wild terror of animals on the way to the slaughterhouse is no different than our own terror when we discover ourselves under threat. And we’ve slowly learned that the whole industrialized meat system comes at a cost to our health and to global warming and the environment in ways we never understood. Singing “We Are from Iowa” just doesn’t have the same ring.

I don’t let myself off the hook. I still eat meat, but it’s a different experience now. We eat less meat in my household, and we try to be respectful of the meat we do eat, recognizing that it comes from an animal not unlike ourselves. We’re in the process of extricating ourselves from the industrial system one tentacle at a time.

I know what’s going on. I know that soil loss from industrial farming, occurring way faster in the US than the soil can be replaced, threatens the very resource that made Iowa special. We squandered our inheritance, and we can’t seem to get off the tilling/fertilizer/pesticide/herbicide cycle that’s at the heart of the problem, farming practices developed at agricultural colleges and that the cooperative movement and my father promoted.

I know farm subsidies keep the system in place, and those subsidies, originally initiated to help farmers, now mostly exist because of greed. I know the industrialized slaughter continues—how else could we support the nation’s addiction to fast food? Apparently, we are easily duped by advertising and by large commercial forces that play us. Our food system needs to change for many reasons, including the environment, global warming, and our health, but it’s hard to turn those trains around.

In a recent return to the Midwest from my home in Vermont, I experienced no nostalgia. Instead, with global warming and the political environment of my home state, the place feels doomed—the small farming towns barely holding on. Maybe it’s not doomed, and something else will arise. Forces are at work for change—good people doing good work, one farm at a time—young farm couples who want to make a difference and change the direction, bringing back the soil fertility that was wasted, strengthening local food systems, raising animals humanely, cognizant that we have their lives—and perhaps their souls—in our hands. It’s a huge task. I can do my part by supporting them. They are my heroes.

Ultimately, we must face the implications of the quote by Czech writer Milan Kundera at the beginning of this essay, as uncomfortable as it might make us feel. Whether we believe in retribution for what we’ve done by some God or from some karmic principle inherent in the universe, there is a simpler and more profound reason for questioning ourselves about our treatment of animals. Our alienation from animals is just a symptom of a deeper alienation from ourselves, a lack of attention, a failure of imagination, a failure even of love, and cause and effect—what you sow you will reap—means we’ve gotten away with none of it. Unfortunately, we’re pulling down the rest of this world’s incarnation with us.

The amazing thing is that while there is no rabbit to be pulled out of a magic hat to save us, we can still make choices, salvage something, and grow up to our responsibilities. I have two books on the end table beside me that are part of another force in the world, trying to counter the damage—Ed Yong’s An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us, a review of the amazing current research about animal senses that should humble us, and, more quietly but movingly, Helen Jukes’ A Honeybee Heart Has Five Openings: A Year of Keeping Bees. It’s a beautiful small book devoted to a year in Jukes’s life when she began beekeeping. Those tiny pollinators changed her life. There are so many scientists, philosophers, artists, and thinkers working to help us find our way through to a new way of relating to the world.

My father relented in later years after a move to Kansas City where he worked for Farmland Industries training co-op managers. He began to eat meat. My brother Chris did too, though he allowed himself only chicken and fish. I admit I felt relieved—we meat-eaters seemingly absolved of guilt by their change.

In the end, my vegetarian father was a good and honest manager at the co-op where he earned well-deserved respect over the fourteen years we lived in Napier. It’s not clear he ever grasped the inconsistency of his own personal choice at the table with the whole rural system he worked for and supported. In the end, he defended those farming practices long after the evidence of their consequences was clear.

Our changing understanding of the world often strands us in morally questionable positions that are hard to buck—our addiction to cars run on hydrocarbons is now the best example, but surely, it’s possible for us to confront these choices and change. That was difficult for my father—he rarely admitted when he was wrong or acknowledged that a position he once held may have become compromised. He wanted all his opinions to be right forever. He soldiered on, and then after retirement assumed the role of a gentle radical leftist pacifist, forgetting that the system was ever in his hands.

Recommended

The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

A Picture of Stack Lee

Crossing Paths