Art Nowhere Else: Thoughts on the Literary Magazine

I’ve long struggled getting the idea of literary magazines into language. Talking and writing about magazines has always felt wholly inadequate. They’re kind of like a book . . . but not quite. They’re kind of like a conversation . . . but sort of one-sided.

My favorite definition of magazines has long been one from Tod Lippy, editor of the eccentric Brooklyn magazine ESOPUS. Lippy defines magazines as “objects filled with objects.”

But, of course, one could define houses that way too. Or those many container vessels in shipyards. Or big box stores. Or even the purses my daughters both once carried around as little girls: magic spaces filled with candy, foreign coins, rocks, drawings. Maybe all of these things are each a kind of magazine.

But understanding these things, what they are, how they function, I think will help us understand their long history as the network of literature and proponents of the literary avant-garde, and then help individuals and communities make decisions about them as we move forward, as writers, readers, and editors, in such areas as editorial and literary diversity of thought and form, the inclusion of various voices, the economics of authorship, and the place of these publications in our various institutions, such as here on this campus, as well as the place of them in our progressive lives, heading forever towards that dot of utopia on the horizon.

I want to talk today, though, about just three aspects of how I’ve been thinking about literary magazines: “Magazines as Rooms Stuffed with Things,” “Magazines as Imagined Nations,” and that “Magazines Are Not Books.”

As I begin to talk about the form and place of literary magazines, the active, centuries old, often marginalized field of literary publication, please remember the refrain about the importance of community in areas of activism, writing, and hope that you’ve heard again and again this weekend from Terry Tempest Williams, Martín Espada, and many others at this conference, a conference hosted by a literary magazine, on the topic of just how we should think of publishing and authorship in the open spaces of democracy. Also, as we all woke up this morning to yet another tragedy, this time over 150 dead in an Easter Sunday bombing in Sri Lanka, let me also begin with this quote from author Stephen Marche’s column in today’s Washington Post about taking his 12-year-old son through the cathedral of Notre Dame just months before the world watched the cathedral burn, about the impermanence of things:

"Now, in the fire’s aftermath, I have the strange, horrific thought that not many people on the planet younger than him have memories of what it is like to walk through Notre Dame as it was. He was hungry. He was tired. He was distracted. And in that tired, hungry distraction lurk the remnants of one of the world’s most elaborate and magnificent creations. That is how frail art is, even art carved out of ancient stones: It survives in the febrile and capricious webs of mere consciousness—distracted, resistant consciousness. In the end, art is nowhere else."

1. MAGAZINES AS ROOMS STUFFED WITH THINGS

Though the literary magazine form reaches at least as far back as Pierre Bayle’s News from the Republic of Letters from late 17th century France, literary magazines have been more of a 20th century phenomena, serving as a voice for the century’s literary movements.

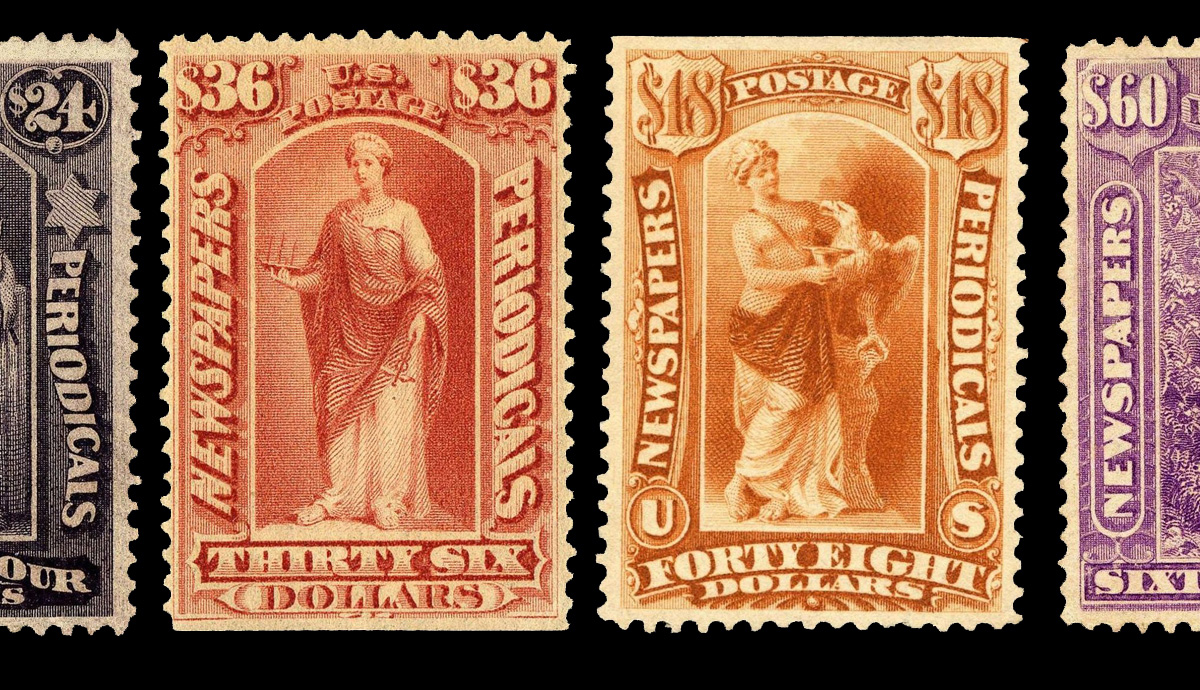

Launched as an early American magazine in 1815, the original North American Review wasn’t a literary magazine as we recognize them today, which is as vehicles that publish work made up of or about literature and art. The original North American Review was a traditional magazine in the style of a miscellany, a word often printed below the title in early issues.

Washington Irving, the first U.S. author to make his living by writing, made his first major literary endeavor by launching a magazine called Salmagundi in 1807, just eight years before North American Review, in the hotbed of early magazine publishing that would change the world and create a reading culture—the name of his magazine signifying that Irving understood clearly that the defining feature of a magazine was its mixture of material, the word “salmagundi” meaning a meal mixed of an assortment of meats and vegetables, a miscellany for the appetite.

Using the word magazine to describe a periodical dates back to 1731, when an Englishman named Edward Cave published The Gentleman’s Magazine. He coined the word “magazine” for his publication from the Arabic word, "makhazin", which meant storehouse.

This makes not only etymological sense, but also common usage sense, as magazines are really paper rooms—and increasingly electronic rooms—within which writing and images are stored for public consumption. Following this line of thought, literary magazines are store houses of the literary bent.

So then literary magazines were built upon the idea of miscellaneous storage, of curating various voices into a literary meal. Therefore, opening that newest issue of North American Review, or of Conjunctions or logging on to Apogee, and seeing that deluge of material, much of which, if you’re honest, you may not get to reading, isn’t a bug, but instead a feature of the magazine as medium.

And so, after being trained to read this way for so long, over 300 years now, it in no surprise we adapted so rapidly to the internet, largely a continuously publishing miscellany, as magazines were the first mass circulation of general content for readers, arguably the building blocks towards the age of distraction we now find ourselves.

Poet William Carlos Williams wrote of his desire for some central structure to support magazines, to recognize their value. Maybe even to make them less chaotic. But later he realized his mistake. “I was wrong,” he wrote. “It must be a person who does it, a person, a fallible person, subject to devotions and accidents.”

2. MAGAZINES AS IMAGINED NATIONS

Every magazine makes up a community of readers who share certain ideas about the world—or in other words, who are similar in some way (such as in interests or culture), either before reading the publication or as a by-product of it.

Any reading experience is an act of community building, for as we read, we are imagining, longingly probably, that someone else is out there (today or in the past) reading a similarly beaten up paperback copy of, say, Richard Wright’s Native Son.

Magazines, though, are particularly interested in this communal reading experience.

I argue in the introduction to my book Paper Dreams that magazine readers create “imagined communities”—in the same sense, in his 1983 book Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson used the notion to describe the modern age of nation building, nations as ideas disseminated via the language of print culture. Here is Anderson’s own description of early newspapers’ influence in the development of national identities:

"We know that particular morning and evening editions will overwhelmingly be consumed between this hour and that, only on this day, not that.... The significance of this mass ceremony—Hegel observed that newspapers serve modern man as a substitute for morning prayers—is paradoxical. It is performed in silent privacy, in the lair of the skull. Yet each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion."

Literary magazines—though perhaps not as homogenous in style and content as the circulated newspapers Anderson describes, and certainly not released daily—have this in common with them: every such publication creates a new community of readers.

This, I believe, is one of the main reasons why modernist literary magazines were so popular in their heyday of early 20th century modernism. In the midst of such overwhelming societal changes—industrial, political, aesthetic, and so forth—the modernist magazines gave people a tie-in to an imagined community of readers. Literary magazines like Margaret Anderson’s The Little Review, which famously introduced the world to Joyce’s Ulysses, and Harlem Renaissance publications like Fire!!, which gave space and circulation to African American voices, fostered a sense of belonging and purpose. In the 20th and 21st centuries, MFA programs and the internet have continued to create that literary community across broad geological and national borders that was already begun in the pages of magazines.

The poet William Carlos Williams once again, who was an enthusiast and active participant in this early 20th century furnace of literary magazine publishing, famously theorized “There are no ideas but in things”—that our ideas, stories, and language come from the objects of this world: mountains, cars, houses, flowers. Of the things he surrounded himself with, Williams held magazines in particular esteem. “The little magazine is something I have always fostered,” Williams wrote, “for without it, I myself would have been early silenced. To me it is one magazine, not several. It is a continuous magazine.” He was able to imagined himself there in Paterson, New Jersey a citizen of a continuous nation of people who cherished the beauty and power of language.

3. A MAGAZINE IS NOT A BOOK

Jerome McGann’s foundational 1991 book on bibliographic literary study, The Textual Condition, was very helpful for me trying to understand why reading a poem or story in a magazine was different than encountering that same text in a book. Though Textual Condition is ostensibly about conducting bibliographic research, it has proven useful for understanding how texts function in contexts—which is primary to the magazine reading experience, as there is much more context of contrast and difference in magazines as compared to books, from the ads to the other texts to circulation signifiers like dates and volume numbers, and so forth. McGann’s overall point is that the study of texts—short stories, poems, advertisements—are material in nature because texts are “empirical phenomena,” or things that occur in specific, definable material environments. McGann called reading in the magazine environment “radial reading,” or continuously reading around, against, or through other empirical phenomena within the same reading experience.

So this is what literary magazine reading is—looking at literary transmissions in time and context. This kind of reading is arguably more organic than the majority of book reading, as it continually forces the context (material and historic) upon the reader. The signifiers found in other poems, the running date in the header, the nonfiction piece set in present tense, the short story in the style of the time. Even what isn’t there, perhaps: science fiction. Immigrant voices. Empirical phenomena of absence and erasure.

Moreover, magazines make context in space and time, that imagined community, a primary aspect of reading: who else is reading this, what month/year is it? And so on.

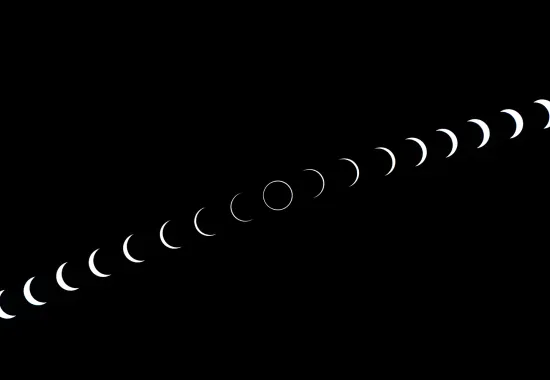

If defined by anything at all—let’s say you make a magazine without miscellany somehow, make a magazine for a readership of one—magazines are unavoidably defined by their periodicity—meaning an inferred or direct contract that there will be another one after this one, and so while reading magazines one imagines a future issue, and, when that future issue appears, that other issue then becomes the past. And this process continues. Or when a magazine, like BLAST or Tin House stops publishing, the process ceases, the issues exist, but the conversation has been silenced, only existing as archive. Literary magazines are literary transmissions purposefully and necessarily yoked to time. They are rooted in space, but to be replaced by a future object, similarly yoked, bearing the same name and purpose—again and again and again.

McGann asserts that all this materiality—this focus on textual context (space, time, object)—is not just a literary concern, but the way we live in language. We are constantly awash in the textual condition, me reading this now, you listening to it, me reading McGann (and my email) while I write these words for a presentation here.

And why I find all this fascinating and these publications important is because it argues that literary magazines embody the contemporary moment differently than books. They draw more attention to time, material, and context, to the act of publication itself.

Jonathan Franzen wrote an essay—later a book—about reading a book as a method of learning to be alone. Magazine reading then is a method of learning to be with others. You can’t read them otherwise; texts in magazines are never singular, always communal.

The literary magazine is a public commodification of art for the public.

The literary book is a private commodification of that art for the public.

A book is a voice, while a magazine a chorus.

Books are site-specific events.

Magazines are continuous events.

Books feel intimate.

Magazines feel social.

A book is an event. It isn’t you.

But you read a literary magazine and think, I could be a part of this.

Scattered across our desks and bedrooms, magazines are metaphors for our lives lived periodically and in installments. Magazines reflect how we live within and labor to construct our fluid contemporary identities, anchored in the present while longing to be eternal, living in the present while believing it’s the future that lasts.

Magazines are born failures, because they all eventually die or transform beyond their origins into something unimagined. North American Review is a good example of this, shifting, dying, being reborn, changing again. “The expectation of failure is connected with the very nature of a Magazine,” wrote American magazine and dictionary pioneer Noah Webster in 1788.

“Communities,” Anderson writes, “are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined.” Books are singular events. Magazines, like marriages and love and life, are promises to an unknown future.

This essay was presented at the North American Review Writing Conference, April 21, 2019.

Recommended

Crossing Paths

I Have Only Dreamed You Dead, For Now.

Encounter