Notes on the Changing Writing Life

Back in November of 1995, when dinosaurs ruled the earth, the North American Review published my essay "Love, Sex, and Power on the Cyber Frontier." The common metaphors for the dawning digital world have since become clichés: the information superhighway has become more clogged than a Los Angeles freeway at rush hour, and the vast, unexplored terrain that was cyberspace has become dotted by seething cities, as dangerous and forbidding as any ill-lit Gotham patrolled by a brooding Batman.

The writing life has changed. New literature has become a commodity because of the proliferation of online outlets, and, like any commodity, its value drops to zero in the face of abundance. There is an awful lot of stuff out there, far too much of it worth very little. Online publishers proliferate like mushrooms after three days of rain and, like mushrooms, grow best on a pile of compost. A few mouse clicks create a blog—like this one. Voila, a new magazine! All that remains is to solicit work from the desperate mobs of writers who are campus-careerists. With the cost of producing a paper volume down to a few dollars because of digital technologies, what was once “vanity publishing” has become “self-publishing.” Everyone knows Walt Whitman published Leaves of Grass. He did not, however, have his friends give it five star reviews on Amazon.com. Poetry itself has become less a literary act than a social act: one publishes poems at any of dozens of online venues, collects work into small, often handsome, books, and then performs readings at local bookstores, campus lounges, or the occasional summer workshop. Poetry has become a forty-five minute entertainment followed by a night out with friends, a few drinks, a few laughs, and, if the poet is among us, some flattery and signatures. Few people actually read the stuff.

We have crowdsourced good taste.

This is not to say that there is not some exquisite work being written: it is just harder to find. Nor am I arguing that diminishing the importance of the gatekeepers—publishers, agents, and the editors of a few select journals—is a bad thing. The democratization of literature only means that like-minded communities must work harder to find voice and each other. If you and yours were once voiceless, that has to be a good thing.

I just sometimes wish democracy was a bit less noisy.

Perry Glasser, a contributing editor of the North American Review, is a Fellow of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for Creative Nonfiction, as well as the author of Riverton Noir (Gival Press, 2012), a collection of short fiction, Dangerous Places (BkMk Press, 2009), and a collection of memoirs, metamemoirs (Outpost 19, 2012). His essay "Love, Sex, and power on the Cyber Frontier" appeared in issue 280.5 of the North American Review. Subsequent essays have also been published in NAR.

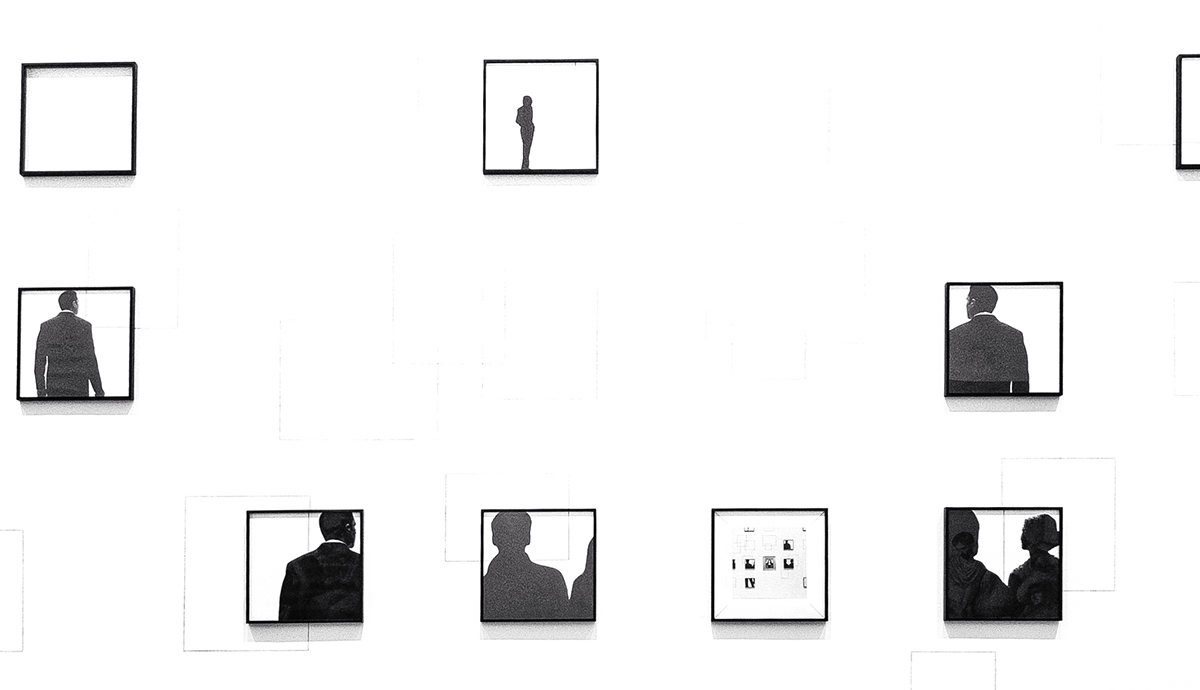

Top illustration by Julie J Seo, a paper-collage illustrator based in New York City. Her clients include Society of Illustrators, 3X3 magazine, Amelia's Magazine, Richard Pearmain, and Visual Opinion Magazine.

Bottom illustration by Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Houston, Texas, just down the road from NASA Mission Control (which accounts for a lot). Clay's illustrations have been featured in the North American Review, most recently in Fall Issue 299.4, the current issue.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop