Notes on "Radar"

Radar

When the bats tore from our attic through the dilute dusk,

we on the lawn watched them satisfy their summons,

the adults explaining natural radar, a human deafness

we would grow to accept. They rode like the sheets

on our pulleyed laundry line, parallel to the meadow,

lofted by a ditch of wind or my expectation

they drop down to us. This radar, we were told,

was like love, sponsoring naked, eggshelled wills

as they advance into the middle distance, each engaging

the other with the self, the seeing to the seen.

I remained innocent of their faces until I saw them

in a museum, pickled like Egyptians, whose display

serves the narrow purpose of proving

what was once known, then slipped away,

now some of the leakage reclaimed and stored.

So this is history, episodic cloud banks hitting

at eye-level for a few centuries, then burning off

while the children wonder if it’s a good beach day.

When their elastic sights are directed past the dune grass

and pert waves, skimming the breadth of ocean,

they see all they know: color, shape, that blue disguise

borrowed from the sky. And we parents sit residually

in lawn chairs, whose webbing embosses the backs of our thighs

with tinsel and rust, until it seems late, our laps ease away,

and we wear the pattern of right angles home to the early dark.

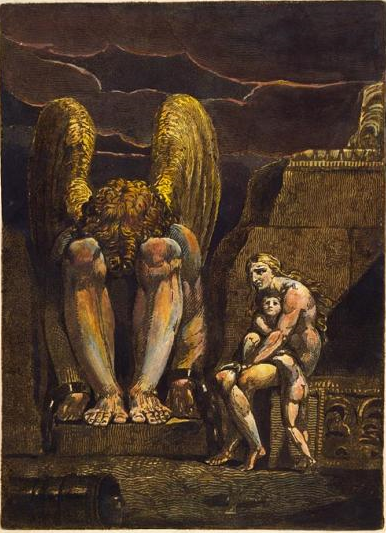

“You're looking all around and your eyes are getting in the way,” says a bit player in a 1950s movie. “Radar” too wants to unburden itself of traditional sight, become a Tiresias of sorts. It summons echolocation—a sightless sight—to capture the invisible, unveiling our habitual disguises, which persuade us that everything resembles something else. Then we are afforded a longer view, not dissimilar from the Etruscans' picture of time as a sequence of “cycles,” each a period reckoned by the longest life: a cycle does not close until the death of everyone who was alive at the festival celebrating the end of the previous cycle. Nothing is past until memory dies.

We often say memories are graven or etched in the mind. To make an etching you submerge a metal plate into an acid bath or mordant (for biting). The areas that have been unprotected undergo a reaction, and once inked, the image is rendered. “Radar” is configured as a series of acid baths, a re-dunking of the worked surface along stations—bathtubs both welcoming for their warm invitation and bracing in their charged plunge—of history's orbiting course, from ancient Egypt's concept of death to our childhood grasp of abstractions like love to the grown-up secret we share: knowing that we don't know. The poem is an attempt to train time to set, and of course it's a failed one.

Amy Bagan's poems have appeared in Denver Quarterly, Northwest Review, and Southern Poetry Review among other journals and have been awarded the Grolier Poetry Prize, the Montalvo Poetry Prize and an Academy of American Poets University Prize. Her manuscript, “Sand-Blind,” was selected as a National Poetry Series Finalist. She has worked in book and magazine publishing (Columbia University Press, the Paris Review, Newsweek, Piano & Keyboard) and as a teacher of English Composition at Venice's University, Ca' Foscari.

Recommended

The Shirt

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings