Obligation from the Elephants

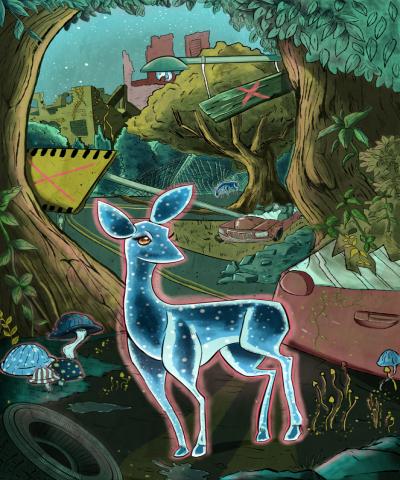

I wrote “Parallelism” as I thought about the animals of Sri Lanka. I lived there for a year while teaching at the University of Colombo, the capital city (Fulbright Fellowship). Sri Lanka had an absolutely marvelous wildlife population, many of these endemic. Many of the others, such as the sloth bear, the M. meminna, the world’s tiniest deer, and the star tortoise were well-known—but not to an Iowan farm girl. With this enormous wealth of animals I had never seen or known existed, and many chances to see them in the wild with local experts, I spent most of my free time with the animals—or as close as I could get.

However, not all the evidence of wildlife in Sri Lanka was out in the jungles or on the rivers and shores. I had been a guest in several local homes where leopard heads and pelts were part of the decor. In one home, a mounted alligator head had fallen off the wall and was sitting with jaws upright on the floor of the entrance hall, and enormous elephant tusks were displayed above the mantel, above the server in the dining room, crossed for display on the walls. These had been fitted with silver caps over the ends where they had been cut off the elephant’s face.

The elephant has a long and rich history in Sri Lanka. The early kings decreed that elephants must be protected and that anyone found killing or even maiming an elephant was punished by death. This was despite the fact that elephants loved to invade gardens and rice paddies. However, high, tight fences kept the produce intact due to the fact that during this era Sri Lanka was an important exporter of grain and food. The war elephants of Sri Lanka were also world renowned. In fact, Onescritus, Admiral of the Fleet for Alexander the Great, who was sent to buy war elephants found that Sri Lankan war elephants were bigger, fiercer and more furious than the war elephants of India. Elephants flourished.

The story changed, however when Europeans began to discover the island. Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) was first visited and appropriated by Portuguese explorers in 1505. In 1658 the Dutch took over control, and the British supplanted the Dutch in 1815. All of the European powers were interested in control, commodities, and profits. By the middle of the 1800s many Brits who came were intensely interested in hunting as sport. The most famous of these was Major Thomas Rogers, the Elephant Killer. He reportedly killed at least 1,400 elephants while he was stationed there by the British government, and was also paid a bounty for every elephant killed. He was not alone; two other British officials also killed more than 1,000 elephants each. Major Roberts was warned by a Buddhist monk that he would die—and six months later he was killed and carbonized by a direct lightning strike. Years later, his tombstone continues to be hit repeatedly by lightning strikes.

I felt a great sympathy for these enormous, wrinkled creatures who are in so much trouble from a world that seems bound to make everything pleasant and convenient for humans, at the expense of plant and animal life. When I visited Maligawa, Sri Lanka’s most revered and perfect elephant, while he was dying in Victoria Park in Colombo, I saw that I must speak for him, for the thousands of lost elephants, and for all the other endangered animals.

If there is an elephant Valhalla, then surely Major Rogers is punished every day. And every night the murdered elephants go home to pleasant dreams.

Recommended

Mercy

Eclipsing

Psychic Numbing