On "Most Accidents Occur At Home"

MOST ACCIDENTS OCCUR AT HOME

Nobody tells you this:

Every day is a creation story.

You’ll make a dome of light over waste and welter

some of the time, then wake one night

on your side of the bed and remember:

There weren’t many happy endings.

First the ripe fruit. Then the way he turned from her,

said it was her idea.

Nobody tells you this will happen again

and again. You’ll turn away

from each other, turn back again, wincing

to touch the bones you vowed to share.

Nobody warns you of the day

that’s bound to come. In this story

you are tired, you haven’t slept

in years. There are children close

together and meals to get. You

are in the kitchen getting them.

Your son walks in. You see blood

on his hands. You know

whose blood it is. You shift

the baby to the other hip, you breathe

deep, you say, Wash your hands

and come to the table for dinner.

This poem began with a phone call from an old friend from college, newly married. She’d called to tell me she was pregnant.

“So,” she said brightly, “what’s family life like?”

I thought of these lines from Beth Ann Fennelly’s “Poem Not to be Read at Your Wedding”: Well, Carmen, I would rather / give you your third set of steak knives / than tell you what I know.

Then I thought of another friend who’d called me two weeks after the birth of her second child (her firstborn was eighteen months old at the time). Choking on exhausted tears, she’d asked,

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I’m sorry,” I’d replied, “I didn’t want to scare you.”

Then I went on to tell my newly-married friend that having a family was the best thing she’d ever do. I told her this, yes, because I didn’t want to scare her, and because, for those who desire a family of their own, it seems to me universally true. But also because it’s not socially acceptable for a woman to tell the truth about her family life unless it’s a lovely truth.

My truth at the time wasn’t lovely. I had three kids, ages six, four, and two. I was exhausted, as every parent of young ones is, and struggling with pain and fatigue from a then-undiagnosed autoimmune condition. My marriage was difficult. Of course there were moments of soaring joy born of the magic that only young children can make, but mostly I was just trying to get through the long, gray slog of each day.

Meanwhile, I was learning that no matter how hard we try to teach our children kindness, patience, and constructive ways of solving problems—no matter how hard we ourselves try to be kind, patient, and constructive—the dark pockets of human nature remain: selfishness, jealousy, petty annoyances. We are flawed. We will forever be cutting one another down in the metaphorical field.

And I found that whenever I gave voice to an unlovely truth about my family life, whomever I was talking to would rush to soften it with something like, Oh, but they’re so adorable, and they’ll be grown before you know it!; or, But he works so hard for you and the kids! As if it weren’t okay to say, simply: This is hard. As if these also-true statements could make what was difficult about my life suddenly easy.

So, this poem came into being because I wanted to tell an unlovely truth about family life and not have to take it back. In fact, I felt a responsibility to tell it: People need to know they’re not alone in the bleak seasons of their lives. As I wrote, lines from Adrienne Rich echoed through me: I know you are reading this poem as you pace beside the stove / warming milk, a crying child on your shoulder…

I hope someday we can all tell the truth about our lives without qualifying—as you’ll note I did above—the darkness with the light. I hope someday we can talk in terms of the both and rather than the yes, but.

I love my family viscerally, fiercely, and forever. Having a family is the best thing I’ve ever done. And it’s hard.

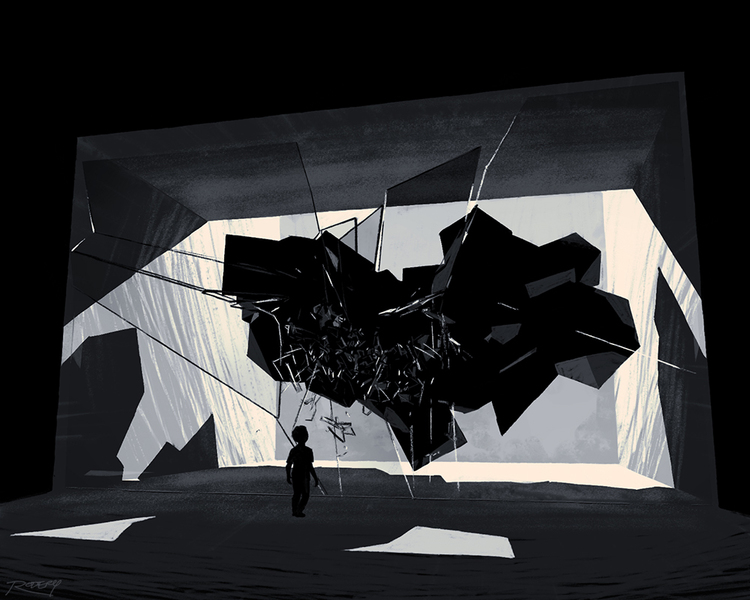

Illustration by Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Clay’s illustrations have been featured in the North American Review, most recently in issue 301.1, Winter 2016.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop