On Donation from issue 299.4

It is not a quick and dramatic emergency room reveal; it a process of many tests and scans, after each of which you may get the phone call that interrupts your day: you cannot save your sibling’s life. In this fall’s issue of the North American Review, my poem, “Love Poem to my Kidney,” will appear. It is a poem about the time about a year after my brother’s kidney transplant, for which I was the donor. What many don’t know is how very many steps there are to become a donor.

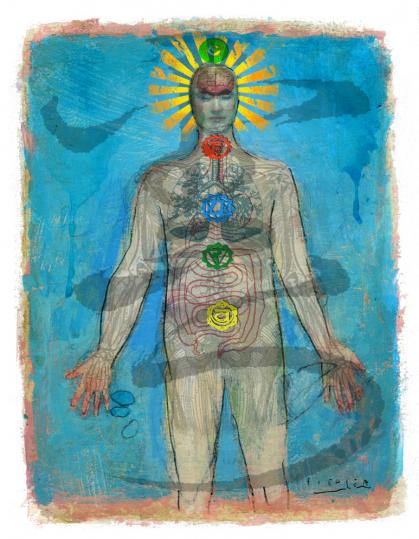

With such buildup, in such a sterile, halogen medical environment, there’s plenty of time to ponder why we try so hard to be in control of our lives, despite knowing we ultimately have little control. It is from this thought that I reached out to ancient Egyptian burial customs. (I’m quite sure this is what the graying man having blood drawn next to me for the glucose test was thinking.) After all, these folks mastered holding onto life. They had a system. If they had to leave, they were going to take it with them when they were gone. Whether they succeeded or failed, the attempt at controlling the continuation of life drove them, and the mythology and ritual involved, handed down, provided them the ability to feel some sense of taking action.

But not so with the kidneys. In fact, there is no clear indication that this culture had a word for kidney at all, likely because they thought it had no significant function. The liver, stomach, intestines, and lungs all went into separate canopic jars and were buried with the body so that they could be taken to the afterlife. But the kidneys were left in their bodies. The heart stayed in the body too, but for the opposite reason: the heart was so sacred, being where the soul was, that its integrity had to be maintained, so that it could be weighed in judgment against a feather after death.

It was unsettling to me that this culture so consumed with holding onto life after death thought nothing of the body part that was so consuming my life and that had consumed—in thought and quite literally—my brother’s life for a decade. Our attempt to hold onto a life hinged on the organ that barely existed in this other culture. Yet we are the same: asking just a little bit more of our bodies than nature intends.

And we were successful. Modern medicine took one of my kidneys, thereby turning the other into a giant kidney. Modern medicine built arteries so that inside my brother’s body a third kidney could be connected and also double in size. And scar tissue did what it was supposed to do—bandage, build, take from my brothers body to disguise what had been someone else’s as his own.

And after all of the ritual, the waiting, the cuts, the bandages, there is only quiet. There is healing. There are scars that are at once lovely and grotesque, covered up and my badge of honor. Such a process. Such a long struggle. Such high stakes. But for it, no name.

Emily Schulten's poems appear in Prairie Schooner, New Ohio Review, New Orleans Review, Fifth Wednesday, and others. She is the author of the collection titled Rest in Black Haw (New Plains Press). She teaches English and creative writing as an assistant professor at the University of West Georgia. She will be featured in the 299.4 Fall Issue of the North America Review.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop