Origin of Black Boy

It is 2016 in the middle of winter.

However, MoMA is warm.

I am part of Star Black’s “Writing in Response to Art” class which meets on Saturdays. The course involves our ragtag team of writers heading to the museum of the day to write pieces inspired by the works there. Often, we head to the locations with only Professor Black’s prompts in our hands, our bags, and our trusted notebooks and pens.

I have never been to the MoMA before; in fact, most of the things I’ve been exposed to since becoming an MFA student so far seem to be a bit too rich for my blood, both figuratively and literally. Being Brooklyn-born and raised has shaped many of my tastes but has not carved them permanently in concrete.

So, it is on this particular day that my eyes fall on a painting that stops me cold.

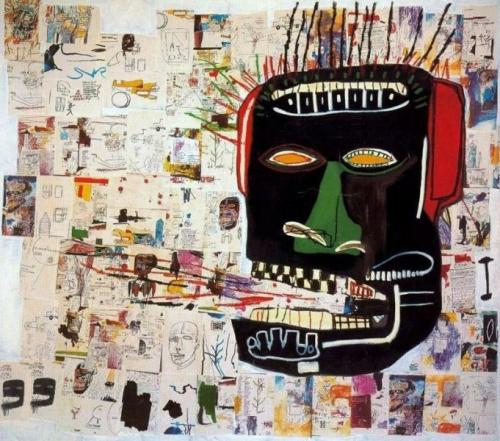

When my muse strikes, it is less like harps or a lightbulb; rather, it is lightning striking down and splitting every nerve or it is my skin rippling in shivers, as if immersed in a freezing pool. Before me in all its huge, bizarre glory sits a painting called Glenn. A Basquiat original, it depicts a big, black skull with different, smaller images surrounding it. It looks as if it is breathing fire. I take out my notebook and pen. Somehow I balance my writing gear and Professor Black’s prompts with little effort. Instead, I am too drawn to the dancing happening between the painting and the lines forming in my head. The five words on the paper—Professor Black’s prompts—somehow find themselves weaving into the lines I jot.

When the work is finished, I look down and reread what I wrote. Normally, when I write, I try to finish getting down my ideas before I read the product. I never know what I’m writing about until I’m done and this work is no different. However, as my eyes touch each word my mouth utters, I have a clearer sense of what I’m seeing. Each paint stroke makes me think of Jesse Washington. His death was a lynching, burning, punishment, and sacrifice all at once. Although it isn’t my intention, Mr. Washington has become a macabre placeholder for every black body that has been hurt, humiliated, and killed; he has become my symbol for America as of late.

I stop and, despite being averse to titles, give it the only name I think will fit.

I call it “Black Boy.”

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop