“Out-Of-Touch, In Touch, To Touch: The Role Of Sense-Based Poetry In The Digital Era”

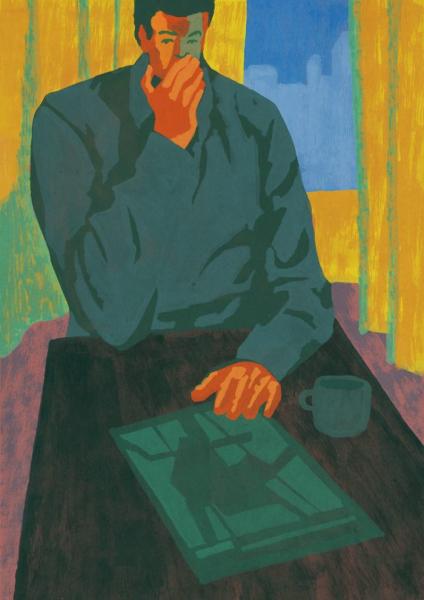

My arsenal when I enter my poetry workshops is seemingly innocuous: a pen, a 99¢ notebook, and a clay mug that contains a stapled together tea bag. The tea, bought in bulk, doesn’t hint toward a distant land like Masala Chai nor does it promise a feeling like Calm Chamomile. No, my stuff is just stuff that one could have purchased, and did purchase, decades ago.

After I arrange my supposedly timeless things, it doesn’t take long before I start in on a supposedly timeless topic in writing classes: detail. Writing instructors have many methods for communicating ways to create authentic details, but I don’t think I’m alone in preaching the value of engaging all the senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. As I trot out my various exercises (my favorite one being to kick them out of the classroom so that they gather details from campus)—I have to wonder if everything about me—from my paper, my pen, my tea, and my belief in detail—is out of date.

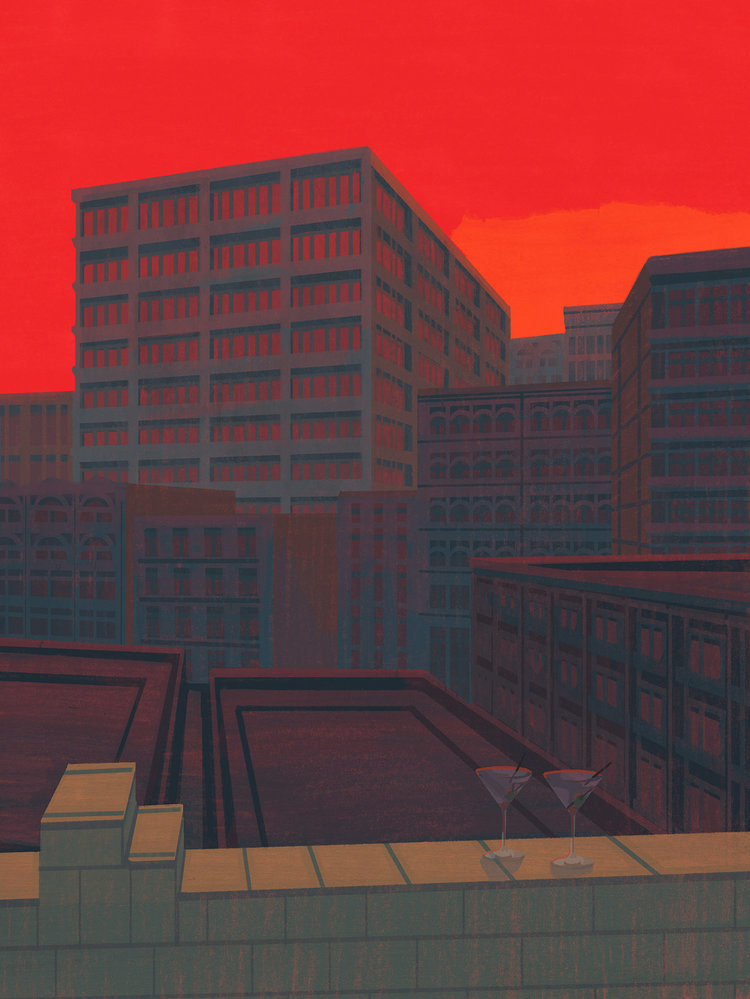

I can’t help but feel as if a belief in knowing one’s senses, in being present—in essence, my particular role as a poet—is out of touch in a world where real life is continually mediated through technology. Real life, or “R.L.” it’s called now, like a pet that’s mentioned once there is a lag in conversation. All of this leaves me wondering: What is the role of sense-based poetry in a time of increasingly de-sensitized living?

Will there be a movement in poetry that values (maybe even over-values to the point of romanticizing) that poet-sitting-under-a-tree thing and gazing out at the world, conjuring up wisdom? While I find that conception of a poet to be more mythical than real, myths are powerful, even necessary to social cohesion and well being, cognitive research tells us. And in a world that prefers images to reality, maybe that’s just fine. Maybe that gives poets a place. Since the Romantics claimed our interior lives as fair game for subject matter, many poets do assume this stance of Poet as Prophet. If one is writing about one’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences (as opposed to creating characters, for example), then those thoughts, feelings, and experiences perhaps should offer readers insight. Many poets have adopted the process (and sense of self-inflation) that Wordsworth expressed in Lyrical Ballads: “… Poems to which any value can be attached, were never produced on any variety of subjects but by a man, who, being possessed of more than usual organic sensibility, had also thought long and deeply” (emphasis mine).

At the same time, I think we can all admit to there being a lot of pseudo-profundity out there, poems ending with some squishy line like “And now, the wind.” At first, the openness feels interesting, but upon further testing, what’s being said is really not all that much. When we see variations away from this stance, like with Fredrick Seidel’s work, we may feel an attraction because that’s not the poet your mother thought you should date. But I digress. In many ways, this Idea of Poet has long been with us, but how will it change, (how has it changed?), since emerging poets don’t share my sense of a “before” that did not include the internet?

Will poetry move away from its dependence on detail, experience, and image to reflect a world that is continually digitizing these elements? Perhaps move more toward broadcasting persona than sense-based perceptions? Or collaging all these random bits of images, words, and performances so that poet acts more like fishermen in a perpetual cycle of catch and release.

Frankly, is all of this already here?

As Joel Whitney explained in a review of Mark Strand’s book last year, “Poets embrace pop or pursue the workings of the mind with what Robert Bly called associative leaping. They examine rhetoric by mashing up archaisms with the hyper-new. They resist poetry’s traditional resistance to technology, fashion, advertising or fad — or they follow someone like Ashbery into poetic abstraction.” Indeed, embracing technology is evident in many ways such as the growing complexity of video poems. And the number of poems that create arresting juxtapositions with a pile-up of pop cultural references adds a cool factor to poems. At the same time, it can do so in a way that’s a bit too aware of the need to be hip, similar to when my 70-year-old mom says, “Starbucks is cool.”

But there is an irony here, one that speaks to our relationship not just with R.L. but with science, something that is both as fantastical and real as you can get. Since our understanding of the earth’s rotation, science has evolved from learning through sensory perceptions to learning through instruments and calculations. The technology (iPads, cell phones, internet) that allows us to live, not immediately or directly, but through something—a screen, a photo app, an internet connection—is wave-particle duality of the quantum world. But very few know about that, or care to know about that. Just one more example of this disembodied stance.

But there is an irony here, one that speaks to our relationship not just with R.L. but with science, something that is both as fantastical and real as you can get. Since our understanding of the earth’s rotation, science has evolved from learning through sensory perceptions to learning through instruments and calculations. The technology (iPads, cell phones, internet) that allows us to live, not immediately or directly, but through something—a screen, a photo app, an internet connection—is wave-particle duality of the quantum world. But very few know about that, or care to know about that. Just one more example of this disembodied stance.

Quantum mechanics has allowed us to understand that which is invisible. But this knowledge, for many of us—and myself included—has separated us from nature and ourselves. Alan Lightman, a theoretical physicist as well as a novelist, beautifully articulated this idea in his latest book: “Consciously and unconsciously we have gradually grown accustomed to experience the world through disembodied machines and instruments.”

Let me immediately say there is value in a disembodied and technologically-mediated existence. Much of what I write is transmitted through these mediums, enabling me to find a readership outside of my small Midwestern town. Frankly, it would be absurd to pretend we are not greatly benefiting from what technology has offered writers. And I don’t want to suggest a false dichotomy: if you tweet a lot, you cannot also participate in real life. I’m just wondering, though, about the increased use of technology to mediate our experiences. How might the continued dependence on technology alter sense-based writing? If one is accustomed to taking a picture of an interesting scene—ladybug on maple leaf, protest by the school cafeteria, sunset over a corn field—instead of taking the time to stop, stare, appreciate as many of the sense-based details as possible—what is lost?

My response is something quite simple, but increasingly difficult. I try to take breaks from it all. I try not to check email until after I write and exercise, for example. I try not to post what I’m doing if I’m with others. I try to just sit, just be, a little each day. All I know is that I feel increasingly like the old-man-out as I don’t update my Facebook account or forget to take a picture because I’m soaking it in. The work that I do, and maybe this is pompous on my part, takes a lot of concentration. If my phone were pinging right now, I wouldn’t be able to articulate what I’m saying. Maybe others can. And maybe that will be what is valued more and more in the future: a mind continually sliding between screen and being.

Despite the fact that I am constantly reading current poetry, I always feel as if there is so much more out there. And that sense of keeping up (or FOMO) doesn’t take into account how in our Age of Outrage there is a new literary controversy whenever I hit refresh. So, any statements about what poetry is or what poetry is going to be—I cannot make. All I know is that as I am exploring how to erase myself in my poetry, which is one of my current interests and perhaps a response to a more disembodied existence than what my poetic forebears had. I’m wondering how the erasure of self through sensory immersion differs from that through digitization? With marketing algorithms and inadequate privacy laws, online sites tend to codify us, turn individuals into tidy categories that are most likely to like some product, petition, or person. Will we continually lose ourselves in this collective space and then resist it again and again? How might that impulse manifest itself in our art?

Here is where I must come to some sort of conclusion, and here is where I’m offering a cupped palm of infertile soil. I do not know what the poetry of the future will look like, but I suspect it will look more like imagined experience than actual experience. In the meantime, I will continue to study a maple leaf as if my life depended on it, because, for me, my satisfaction with life does depend on a few simple, unmediated acts.

Works Cited:

Lightman, Alan. The Accidental Universe: The World You Thought You Knew. New York: Pantheon Books, 2013.

Wordsworth, William. Lyrical Ballads. The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Age of Romanticism. Orchard Park: Broadview Press, 2006.

Whitney, Joel. “Almost Invisible: New Poems by Mark Strand” from NPR Books. 3 May 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2014. http://www.npr.org/2012/05/03/151438518/almost-invisible-new-poems-from-mark-strand

Recommended

Mercy

Eclipsing

Psychic Numbing