True Stories

When I was forty-two

I slung a duffle over my shoulder

and went to Greece alone.

You know what happened.

You read the book, saw the movie.

I opened the door, walked in

and there he was—

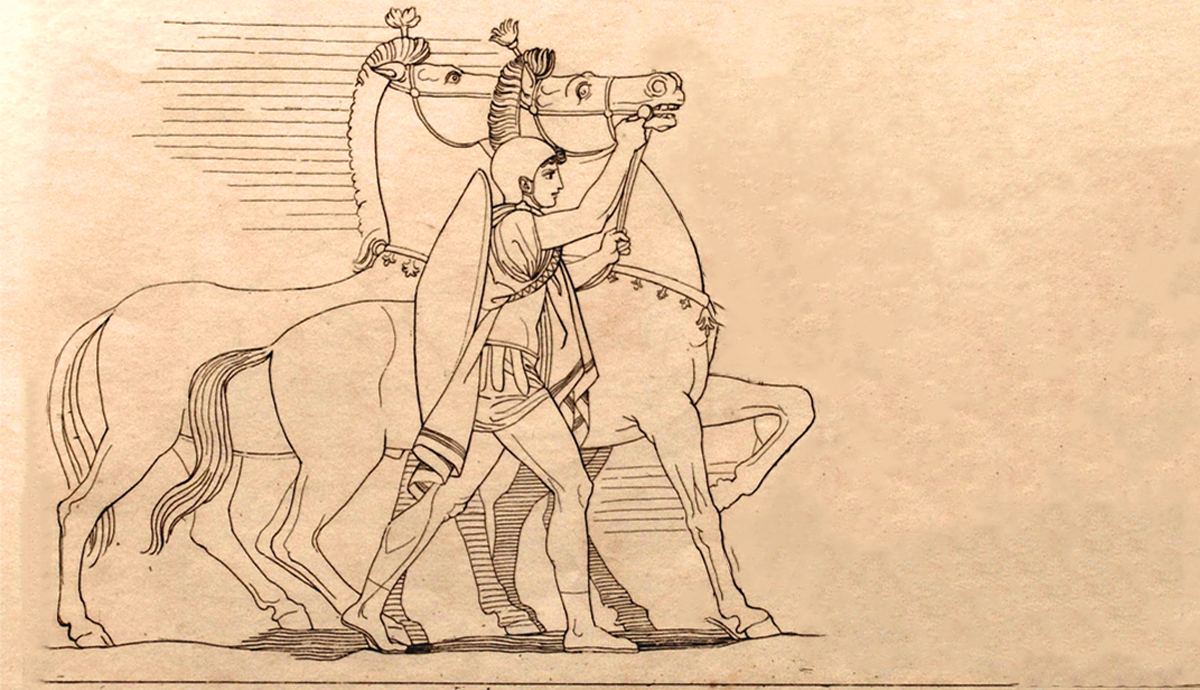

Diomedes, Breaker of Horses.

No plumed helmet, no horses.

No wine-dark sea, no sword,

no chariot, but, yes, in the flesh—

stuck at a desk in an office.

I stopped in my tracks

Athena, koritsi mou, give me that.

You could write this poem yourself

*

But that poem isn’t this poem.

This is about 435 Greek men, Jews,

from Corfu. Big men, strong men.

Iron workers, mill workers, construction

workers, dock workers, ditch diggers,

furniture movers. Lifters and haulers.

And how when they were rounded up

and sent to the death camps they were

singled out for their size and strength

and assigned to be Sonderkommandos—

those who under SS whips and clubs

struggled with iron hooks to drag

the dead from the gas chambers,

tear apart the knot of tangled bodies,

yank the gold teeth and feed the flesh

to the ovens. Twenty thousand a day.

This is a story about 435 Greek men

who refused. Which means they were shot,

burned, and up the chimney with everyone else.

If you believe in heaven, they entered clean.

If you don’t, well, no good deed goes unpunished.

This is a story about heroes,

and I wonder what my Demetrios—

for that was his real name—Demetrios

whose muscles strained the seams of his shirt,

whose upper arm I couldn’t fit two hands around,

whose black chest hair warmed my neck, my breasts,

who never knew I was Jewish, and if he had

with all his masculinity and Greek pride, what

would he have done? Diomedes, Breaker of Horses.

Alice Friman’s most recent collection of poetry is Blood Weather from LSU. New work is forthcoming in Hotel Amerika, Cloudbank, Crazyhorse, Plume, and others. A recipient of a Pushcart Prize and included in Best American Poetry, she is Professor emerita of English and creative writing at the University of Indianapolis and now lives in Milledgeville, Georgia, where she was poet-in-residence at Georgia College.

Recommended

The Shirt

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings