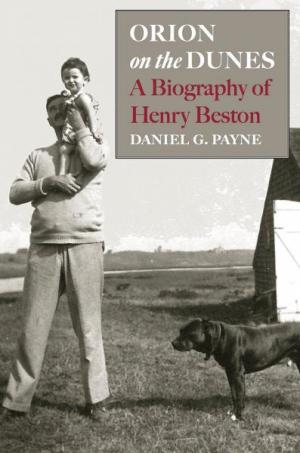

"Q&A with Daniel Payne about Orion on the Dunes"

Note: This interview was begun informally in person, and then continued more formally through email.

Charlotte Zoe Walker: Orion on the Dunes strikes me as a brilliant example of the art of biography. Were there any particular biographers who you thought of as role models while you were researching and writing this book? What aspects of their work were most helpful to you?

Daniel G. Payne: Because it took so long to do the archival work for the Beston project, I had plenty of time to read biographies, and some of the works I really admired were Lewis M. Dabney’s Edmund Wilson: A Life in Literature, Douglas Brinkley’s The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America, Donald Worster’s A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir, and Brenda Wineapple’s Hawthorne: A Life (Brenda was one of my professors at Union College when I was an undergraduate). I took a great deal away from all of those biographies, including the care they took in researching their subjects. One of the other things I admired in all of those works was how they situated their subjects in the literary, political, and cultural currents of their time. In a sense, all of those works were intellectual histories as well as biographies, and this was something that I aspired to in my own work.

CZW: At a recent reading, you mentioned that the title of the book came to you very early on, even before you had actually begun writing. Can you say a little more about this, and how it fitted in with your process of developing the book?

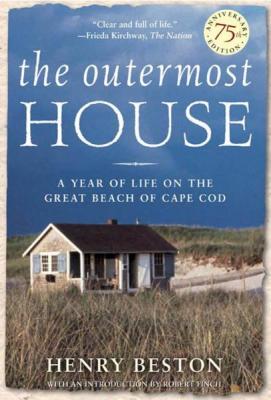

DGP: The final chapter of Henry Beston’s The Outermost House is entitled “Orion Rises on the Dunes,” so the title was inspired by Beston himself. The title is also closely tied to what I saw as one of the major themes of the biography. The constellation Orion the Hunter was Beston’s favorite, and I saw his time on Cape Cod as a quest to find meaning in a world that had been upended by the Great War. Like many of his contemporaries in the Lost Generation, Beston was searching for an alternative to the institutions that had been called into question by the war, as well as a way of healing from his experience in the war, and on the Cape he found that in the eternal rhythms of nature.

CZW: Did you intend the structure of the book to be symmetrical, building from the beginning to the central chapter on Outermost House, almost like a pillar, with the later chapters falling away from that peak, in a structural sense?

DGP: Yes, absolutely. I thought of it as the center pole in a big tent. I knew that most people who knew something about Beston already had been introduced to his work through The Outermost House, and they would want to know more about this period of Beston’s life. But while I thought of this as a high point in his life and work, I also wanted to introduce readers to some of the other wonderful books he wrote, as well as his life before and after writing what is one of the classic works of twentieth-century American literature. Some of the other works by Beston that I have come to admire include works such as Herbs and the Earth, Northern Farm, The St. Lawrence, The Book of Gallant Vagabonds, as well as the fairy tales he wrote after the Great War.

DGP: Yes, absolutely. I thought of it as the center pole in a big tent. I knew that most people who knew something about Beston already had been introduced to his work through The Outermost House, and they would want to know more about this period of Beston’s life. But while I thought of this as a high point in his life and work, I also wanted to introduce readers to some of the other wonderful books he wrote, as well as his life before and after writing what is one of the classic works of twentieth-century American literature. Some of the other works by Beston that I have come to admire include works such as Herbs and the Earth, Northern Farm, The St. Lawrence, The Book of Gallant Vagabonds, as well as the fairy tales he wrote after the Great War.

CZW: As I read your book, I was often very moved by your presentation of Beston’s story. I am left wondering how writing it might have affected you. Aside from what must have been a very challenging job of research and composition, could you say anything about how writing this book affected you emotionally or spiritually?

DGP: I have always found what Beston had to say about nature to be important in terms of his impact on the growth of modern environmentalism, but as I came to know more about him and his work, what he had to say about the healing power of nature and the subject of how modern industrial society has distanced us from the elemental (one of his favorite words) aspects of nature and its rhythms—the seasons, day and night, etc.— also struck me as something that is worth remembering. I agree with Beston that such things as the frenetic pace of modern life and our disconnection from nature are things that distance us from our own basic humanity.

I was also struck by how Beston went through periods where he doubted himself and feared that his work (with the possible exception of The Outermost House) might be forgotten. Given how much he experienced and achieved in his life, it seemed to me that this was somewhat sobering, particularly since he lived what I consider to be an extraordinary life.

CZW: Did your opinion of Beston as a person change as you worked on Orion on the Dunes? Did you like him as well at the end of your journey as you did at the beginning?

DGP: This is an intriguing question—my opinion of Beston was constantly changing as I learned more about him. One thing that kept me from making snap judgements about some of the more puzzling aspects of his life was constantly reminding myself of the importance of historical and personal context. For example, I was surprised that he was so distrustful of FDR and was adamantly opposed to the entry of the United States into the Second World War, a topic I discuss in the biography. While I was working on the book, I was constantly aware of the biographer’s ironic situation—as a chronicler of Beston’s life, I was taking on an “expert’s” role in interpreting his life, and yet if I had to explain some of the choices I’ve made in my own life, I would be hard put to conclusively provide adequate answers.

CZW: This may seem like an odd question (and no need to answer if it seems inappropriate or trivial)—but I noticed that among the many interesting photographs in the book, there were very few of Elizabeth Coatsworth. I wondered if photos of her were hard to come by, or if there is a story behind that paucity of photos of Elizabeth, and Elizabeth and Henry together?

DGP: I am somewhat embarrassed to say that I really hadn’t noticed this until you pointed it out. There are quite a few photos of Elizabeth Coatsworth, and a future biographer will find a wealth of archival material and photos of her. She really does deserve a biography, too—she wrote over a hundred books, won the Newberry Award for The Cat Who Went to Heaven (1931), and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

DGP: I am somewhat embarrassed to say that I really hadn’t noticed this until you pointed it out. There are quite a few photos of Elizabeth Coatsworth, and a future biographer will find a wealth of archival material and photos of her. She really does deserve a biography, too—she wrote over a hundred books, won the Newberry Award for The Cat Who Went to Heaven (1931), and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

As I think of it, however, there is another reason that influenced our choice of photographs. Many of the family photos that were considered for inclusion in the book were ultimately left out because the digital quality of them was so poor. We included a few “one of a kind” photos of this sort but had to leave out many others.

CZW: This biography of Henry Beston fills a gap in the history of American nature writing, and seems long overdue. I understand that a few others who thought of writing a biography did not receive the same access to family members and family records that you did. Can you say a little about your experience in getting to know Henry Beston’s family or visiting some of the places associated with his life?

DGP: As I mentioned in the acknowledgement to Orion on the Dunes, one of the most important strokes of good fortune that I had was when Barry Lopez came to visit us at SUNY Oneonta. At one point, Barry asked me what I was working on and when I mentioned that I was hoping to work on a biography of Henry Beston, he offered to call Beston’s daughter, Kate Beston Barnes, and introduce me (very typical of that generous soul!). Kate was extraordinarily gracious and provided me with an incredible amount of material and time for interviews, as well as introducing me to people such as her cousins Marie “Mimi” Sheahan and Joan Sheahan Schwab, as well as Gary Lawless and Beth Leonard who were caretakers of Beston’s Chimney Farm. They in turn introduced me to Beston’s godson Richard Beston Day and Kate’s four children, among many others. Don Wilding from the Henry Beston Society was another person who was enormously helpful to me and generous with his time and stories of Beston’s life on Cape Cod.

Because of Beston’s close connection to place, I thought that it was vitally important to visit and become familiar with the places where he lived, such as his hometown of Quincy, Massachusetts; Cape Cod; and Nobleboro, Maine.

CZW: As I wrote in my review of Outermost House, I find your voice throughout the book to be both truthful and tactful, that the reader is continuously in the presence of “a perceptive, knowledgeable, reliable and gifted narrator.” I was especially touched by your use of poetry as epigraphs to most of the chapters. Do you feel that your choice of those poetic epigraphs contributed to your finding your voice as narrator of Beston’s story?

DGP: Absolutely! A great deal of thought went into choosing the epigraphs, several of which were from poems written by his wife Elizabeth and his daughter Kate (who was Maine’s first Poet Laureate). I must say that finding just the right epigraph to each chapter was also one of the most challenging and enjoyable aspects of drafting the book.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop