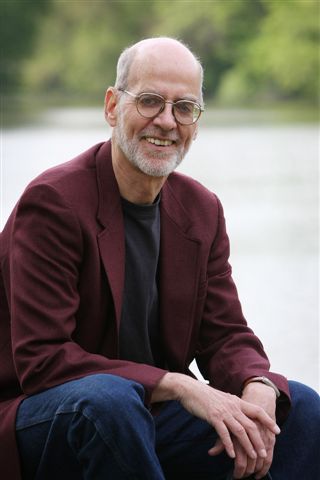

Remembering Philip Dacey

What does one say when a poet dies? Do we mourn the loss of their brilliant mind? Do we say they live on in their work?

Over the summer, the North American Review lost one of its most prolific contributors: Philip Dacey. He died on July 7th at the age of 77 after a fight with leukemia.

Philip Dacey wrote thirteen books of poetry with a fourteenth coming out this fall titled The Ice-Cream Vigils: Last Poems (Red Dragonfly Press). One of his books, Gimme Five, won the 2012 Blue Light Press Book Award. We have a long history with Phil here at the NAR, and we are honored to have worked with him so many times over the years. What better way to honor such a generous art than to return to his poignant and meticulously crafted work? Buy his books. Read his poems. You’ll a few of them in our back pages, including "Thomas Eakins: A Dream of Powers" from 288.2, "The Day's Menu" from 290.6, "Hoofer" from 293.1, "Leaves of Lucre" from 294.2, "Religione Al Dente" from 297.1, and "First Memory" from 300.4. Dacey's Whitman poem from 293.1 called “Hoofer” was reprinted in the NAR Press’s The Great Sympathetic: Walt Whitman and the North American Review. Another one of his poems, “Soldier-Ants,” is forthcoming.

So what does one say when a poet like Phil dies? One says, let’s remember by hearing his words again, by letting them live in our mouth as we speak them aloud.

Here’s “First Memory” from NAR issue 300.4:

First Memory

I’m standing in a crib, my head

just above the railing, which I grip

as I look down onto the bed

where my parents fight, who will not stop

despite all my loud crying meant

to get them to do just that. Am I three?

Maybe only two. The argument

does not end before my memory,

nor do I drop to the mattress and return

to sleep. Throughout, my hands grip the cool

railing, cool even while the burn

of words acts like a lesson in some school.

Did my parents never die? Is it true

they are still fighting, and I am still two?

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop