Remove Udder: Good and Bad Criticism

First the problem. Writers must seek criticism from others, especially those better than themselves (tournament Scrabble players study the strategies of those by whom they are beaten). It’s just like that or you literally lose the plot, and ten chapters later your tender romance that began on the sands of Nags Head has turned into an eldritch fable about the gods of the underworld. And someone has to love you enough – even just during workshop – to tell you that your poem has spinach in its teeth.

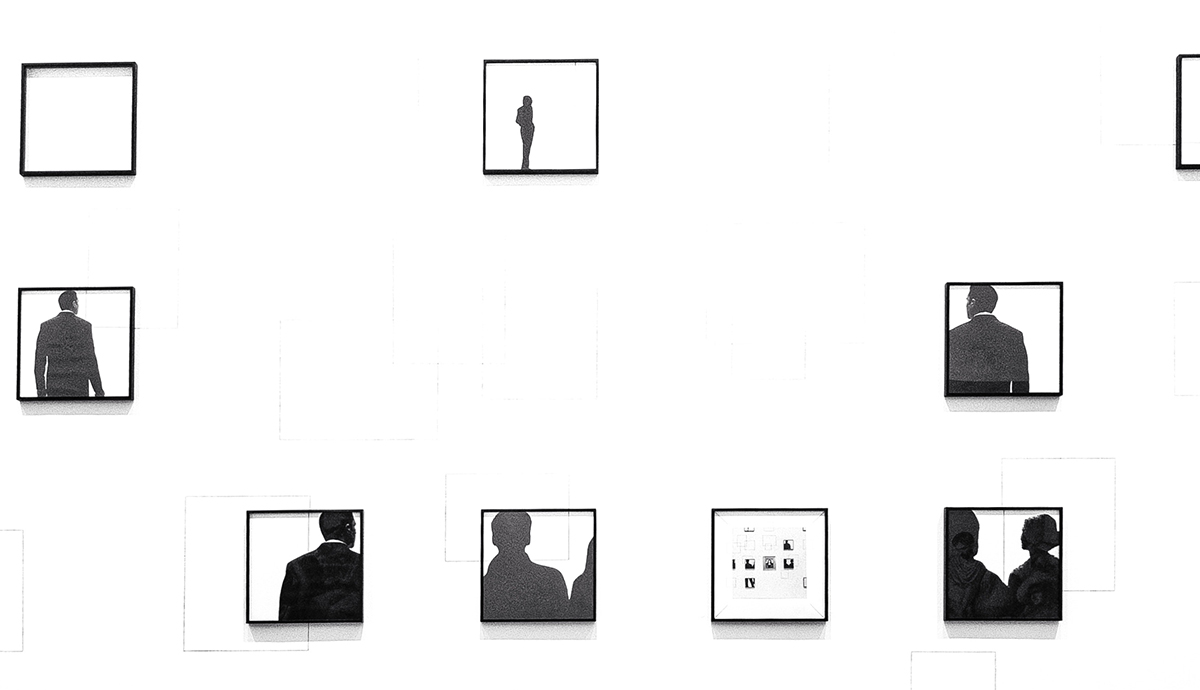

But not all critiques are of equal weight, and you don’t have to take them on board. If a dozen people unanimously say that they didn’t understand that your metaphor meant “penis” (a scene I witnessed, in which the workshopped burst into tears), maybe you need to rethink that metaphor, and no, you don’t have to descend into vulgarity to do it. Yet just as there are those who, when you lay something bare on Facebook, critique your life, there are those who do a worse thing and tell you something uncomfortable about yourself that is actually true. And this time it’s your writing self. And sometimes you have really gone quite wrong and have a lot of revising to do before the thing is ready for prime time. I can only give examples. Some of these are critiques of fact: what honorific titles are and are not used by French-Canadians. Some of these are comments on the language used: over time, in your novella, the non-human character who sounded that way in the first few chapters has crept back toward your own speech patterns. Those are good comments that address a particular and fixable aspect of the work. Some of them, sadly but helpfully in the long run, point out Everlasting Plotstoppers: if the character is a robot on a near-future Earth, then he or she certainly ought to have the Internet, and unlimited data at that, thank you. In fact, to use the phone analogy, he or she should be the Internet, and function as a mobile wireless hotspot. This means that your character should have no need to constantly keep seeking places, while on the run, that have Internet terminals. That means that because of the character’s back story, as you have carefully set it up, he or she would do better to hide near home and not run anywhere at all. So they have no reason to move anywhere, no way to meet the other characters, and there goes your bloody plot. That last one is a thing that happens to people, even very bright people like you (to sound like Anne Lamott for a moment). It happens to writers because we write and sometimes go wrong. So you either right the wrong, giving Robot a compelling reason to leave home, or you consign the file to a USB drive you got as conference swag, and leave it there to hum away in the drawer, unaware of its own flaw. (Full disclosure: I went back and forth with North American Review editor Vince Gotera after he pointed out that the last line of my poem wasn’t really necessary, fat that could be trimmed from the meat. I just had to sit with it until, staring at it, I realized he was right, and approved the change.) But a penis that cannot be identified, and a robot who should really have agoraphobia instead of the wanderlust you’ve given him or it, are things that can be reasoned out. They make sense. You want your reader to know, in a romantic and non-vulgar way, that “she” in the poem is mounting the penis. So, to communicate that, you must rethink that metaphor. If you want the cheese, you must go the other way through the maze. You can use the logical part of your brain to reason with the critic and defuse any initial hurt feelings. But logic balks at the kinds of comments we used to get back on art commissioned for grade-school materials when I worked at a textbook development house. You have a story specifying a cow on her back in a hammock, dear publisher. When you say “Remove udder,” you avoid any possible offense by cow prudes, but you defy anatomy. Likewise, there are comments with an agenda. There are comments that want to drive you toward the critic’s ideology, literary or otherwise. There are comments that are baseless because the critic is upset about a root canal they must have later that day, and they wanted something to pick on, so your writing seemed as good a target as any. There are comments that people make because they sound like something that person heard the workshop leader say: “Oh, I think you’re doing interesting but ultimately bourgeois things with the reassembled narrative.” MFA seekers should especially beware the temptation to adopt the workshop leader’s pet phrases, no matter how smart you think they sound. Learn the difference by studying the critiques people give other writers, so your work, your heart, the sweat of your own brow are not at stake. Maybe the guy on your left in your writers’ group keeps saying the same thing about non-rhyming poems, week after week: “I think this really wants to be a sestina.” (No. Nothing wants to be a sestina except sestinas, and then they all want to have been written by John Ashbery anyway). Maybe your mother is sensitive about the way you’ve portrayed a young mother. Something that breaks you out of a pattern you’ve fallen into, however, is helpful. It’s not even always someone else’s critique: laying out poems to arrange them for my thesis, I discovered I had a bizarre fondness for the word “brick.” Everything was made of brick that year. Brick milkshakes. Listen to your own inner ear. If you didn’t mean something to be a polemic, examine it and de-polemicize it - unless the critic is right and you really are making a harangue pie. Gwyn McVay is the author of two chapbooks of poems and one full-length collection of poems, Ordinary Beans (Pecan Grove Press, 2007). She teaches writing at Millersville University, and will be partying like it's 1525 at the Pennsylvania Renaissance Faire this year. Gwyn McVay is featured in North American Review issue 294.2, March-April 2009. Illustrator Clay Rodery lives in Houston, Texas just down the road from NASA Mission Control (which accounts for a lot). Clay is featured in issue 299.3, Summer 2014.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop