Review of The Body Alone by Nina Lohman

Shortly after I finished The Body Alone by Nina Lohman, I showed a few pages of it to one of my most talented Regis University undergraduates–a junior biology student planning to apply to PhD programs in biomedicine. She read the pages eagerly and then looked up to comment: “This is so helpful. We never hear the perspectives of patients articulated like this.”

Herein lies just one of the major contributions of Lohman’s book, whose subtitle aptly sums up the book’s central project: “a lyrical articulation of chronic pain.” Lohman’s book combines lyrical and narrative writing about her own decades-long experience with chronic daily headaches alongside investigative, research-based writing about the history of pain and how it has been conceptualized medically, philosophically, and theologically. She explores the role of pain in stories ranging from Prometheus to Adam and Eve to Rumpelstiltskin, all while also chronicling 12 years of tests, medications, supplements, and alternative treatments, none of which has successfully cured her of her pain.

Herein lies just one of the major contributions of Lohman’s book, whose subtitle aptly sums up the book’s central project: “a lyrical articulation of chronic pain.” Lohman’s book combines lyrical and narrative writing about her own decades-long experience with chronic daily headaches alongside investigative, research-based writing about the history of pain and how it has been conceptualized medically, philosophically, and theologically. She explores the role of pain in stories ranging from Prometheus to Adam and Eve to Rumpelstiltskin, all while also chronicling 12 years of tests, medications, supplements, and alternative treatments, none of which has successfully cured her of her pain.

Lohman’s documentation of the sensory, cognitive, and emotional experiences of an inescapable, intense, and long-undiagnosed pain gives voice to a voiceless group of individuals–3 million Americans per year–who live with chronic pain. These individuals, Lohman writes, are “Neither sick nor healthy. Both sick and healthy. We are undiagnosed. We are underdiagnosed. We are wrongly diagnosed. Our bodies resist the known categories of disease. Our pain is unstoppable. We are mysteries. We are unbelievable.” Lohman tours readers through the “no-woman’s land” where these individuals (mostly women) reside, “between the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick.” Lohman paints a harrowing, intimate portrait of what life is like for a person with chronic pain: the endless appointments and waiting rooms, phone calls with insurance agents to discuss bills, and the endless medications and their accompanying side effects and risk factors, including the ultimate risk, with narcotics, of addiction. To illustrate the intrusive, all-encompassing aspect of chronic pain, Lohman weaves scenes of her everyday life, including both medical appointments as well as her early years as a mother, alongside collaged text from medical protocols and clinical documentation of her own treatments written by medical providers. The juxtaposition between these modes powerfully captures the inescapable isolation of pain–an isolation that contributed in part to the dissolution of Lohman’s marriage.

The emotional aspects of chronic pain, in Lohman’s rendering, are as unforigving as the physical distress. Lohman powerfully communicates the purgatory of loneliness, frustration, self-blame, and fear that she lives within as year after year passes without even a diagnosis of her condition. She reveals the simultaneous powerlessness and rage that result from living in “a body that has been hijacked,” and shows the heartbreaking loss of dignity that occurs as pain steals away key life moments. A recurring image throughout the book is Lohman stuck in a room apart from her children, suffering in pain while she hears her children laugh in the next room. “It’s not fair that the pain is louder than my daughter’s joy,” she writes.

One of the book’s central points is that chronic pain should be treated not as a symptom of another illness but as its own disease; as a disability; as an aspect of identity (“I both have a body and am a body,” Lohman writes), or as a constant state of being. For Lohman, chronic pain means not “having” pain but “holding” it, hopelessly enduring a pain that is “like perpetual labor cheated the prospect of birth.” The duration and persistence of pain, rather than its severity, is the sticking point for Lohman. “I can suffer hurt,” she writes. “I can tolerate severity. I can mitigate the distraction. It is the persistence of pain that proves problematic [....] I struggle with the realization that pain–specifially the residual, overarching effect of pain–is likely endless.”

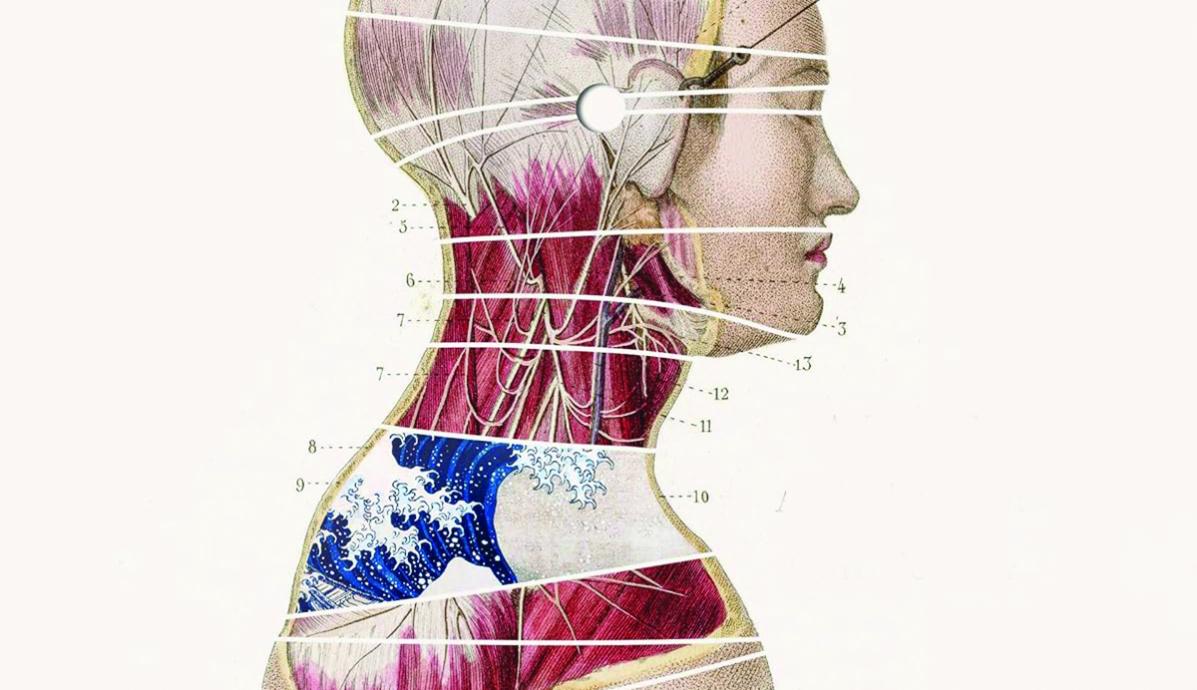

The central problem Lohman confronts in The Body Alone, however, is not pain itself but how to articulate that pain–how to assign language to it in a way that renders it understandable, visible, and believable to others–especially in a context where women’s pain in particular goes unheard. Pain is such a private, personal experience, Lohman shows, that it is almost impossible to render it meaningfully visible to others. Again and again Lohman constructs various metaphors to describe her pain–this is where the book’s lyricism truly shines. She compares her headaches to a fire alarm blaring, to ocean waves swelling and crashing, to a heavy stone, to a convex metal bar, and to a compass needle, among many other metaphors. Although she insists that “illness is not a metaphor,” she also points out that “metaphors allow room to authenticate the nameless. They provide a script outlining behavior and expectations. They challenge loneliness. What I am trying to say is that when we give something a name, we give it an identity.” Naming, Lohman argues, is necessary for making the unknown knowable and understandable-for guarding against the terror of chaos and senselessness and providing “context for the chaotic, hurtful world.” Lohman’s project, then, is to name her pain–to render visible what has been ignored or erased and reach across the lonely, isolating gap between one body and another with the power of language.

At the same time, Lohman also confronts head-on the limits of meaning-making, asserting that pain serves no greater purpose for her and identifying the moments when meaning-making is no longer productive. She also “resist[s] the temptation to make pain beautiful”--an act that, she writes, “is victim blaming when the woman is told to befriend that which breaks her.”

Sexism and misogyny are a major thread throughout Lohman’s book, as she traces how sex differences have been conceptualized and erased in medicine from ancient to present times (including a fascinating history of the “hysteria” diagnosis from Hippocrates through the Middle Ages to Freud). She discusses the ways that “women’s health” focuses entirely on reproduction, and points out that while 70 percent of chronic pain patients are women, 80 percent of pain studies are conducted on men or male mice, resulting in drugs that are ineffective for female bodies. “If pain affected as many males as it does females, would the urgency to solve the problem of pain be heightened?” Lohman rightly asks. She mourns the lives of “centuries upon centuries of women who lived their lives in actual real pain” but were not believed, were unable to communicate, or for whatever reason remained untreated. “I live in a culture obsessed with judging, controlling, monitoring, shaming, hiding, exploiting, denying, claiming, but not actually healing, my body,” Lohman writes in one of the stand-out passages of the book. Alongside this research and rhetoric, Lohman shares personal stories of moments when male doctors (and shamans, chiropractors, and therapists) violated protocol (thereby violating her body), refused to believe her pain, dismissed her pain as mere stress, or treated her with condescension. She critiques the hierarchy of medicine and its perceived ability to cure, heal, assure, or reassure, and demonstrates how most of her encounters with both Western and alternative medical practitioners have only left her feeling invisible and self-doubting. “How can anything be real without proof?” she asks. “Absent evidence what remains?”

Such grand, abstract questions add an even greater level of depth to the book, as Lohman forays into philosophical concerns like “What is the purpose of pain, if any?” and “Why would any God allow people to feel pain?” Theology, for Lohman, is “the study of brokenness”: an attempt akin to mythology to make meaning of human pain by creating stories and assigning names, images, and metaphors to the deepest mysteries. Stories, Lohman argues, “give meaning to our pain.” And so Lohman’s experience of pain becomes a spiritual one as she asks “Can I live with the unknown of this pain as I live with the unknown of God?” She is writing her own theology, her own myths, of pain. “I am curious as to how the privateness of pain parallels the privateness of belief,” she writes.

This is to me the most remarkable feat of Lohman’s book–she succeeds, to a profound extent, in sharing her private pain with the reader in as intimate a way as language will allow. To this effect, she often directly and metatextually addresses the reader, asking for patience, apologizing, or explaining herself as though concerned we, like her doctors, may not believe her when she expresses her pain. She repeatedly warns the reader that, though we might wish for a “proper and resolute ending,” safe and predictable and full of deeper meaning and hence control or agency, her story will end with none of these. Lohman’s story “is a story that doesn’t end,” that “refuses to hold still.” Even so, she invites a deep connection with the reader when, halfway through the book, she essentially begs the reader not to give up on her:

This is when I need you to stay by my side. Don’t leave just because I can’t articulate the nuance of this pain. Nothing, it seems, not my brightest words, not your sincerest empathy, communicates my inner world to your outer world. Please stay with me.

To stay with Lohman is to stay with the 3 million Americans suffering from chronic pain–to investigate and consider pain, to empathize, and, ultimately, to demand change. I anticipate this book will mark a major contribution to conversations about medical inequity, and to disability literature at large.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop