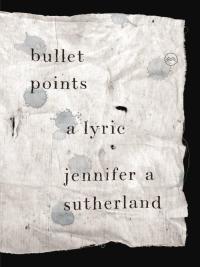

A Review of Jennifer A. Sutherland's Bullet Points

This compelling and challenging work, existing somewhere in the liminal ground of extended prose poem and fragmented lyric essay, invents a form to capture the experience of trauma. The debut book by lawyer-turned-poet Jennifer A. Sutherland, Bullet Points is grounded in her speaker’s two intertwined experiences of shattering violence: her close witnessing of a 2013 courthouse shooting in Wilmington, Delaware, that killed two women and injured several other people, and her own experience of an abusive first marriage. But while we come to understand as much as we need to about what happened, the book resolutely resists narrative and straightforward forms of meaning-making, introducing us to a psyche stunned and at sea, looking for a means to tell and for ways to make sense, while simultaneously remaining aware of the resistant and re-traumatizing aspects of telling. “There are things I need or want to tell you. I am trying. Please bear with me,” entreats the speaker.

As I read I found myself reflecting on the multiple senses in which Bullet Points operates as “a lyric.” Most obviously there is its form, a continuous series of strophes of mostly one or several sentences or sometimes fragments, each to be read as a single line—a literal series of bullet points, surrounded by white space. Equally, the composition moves not in temporal sequence but in poetic interweaving and recurrences of conceptual and historical reflections, memories, shards of quotation, passages of self-reflection, intrusive “scenes,” images real or filmic or dreamlike—a circuit-telling of something too intense and ultimately too extensive to address directly.

As I read I found myself reflecting on the multiple senses in which Bullet Points operates as “a lyric.” Most obviously there is its form, a continuous series of strophes of mostly one or several sentences or sometimes fragments, each to be read as a single line—a literal series of bullet points, surrounded by white space. Equally, the composition moves not in temporal sequence but in poetic interweaving and recurrences of conceptual and historical reflections, memories, shards of quotation, passages of self-reflection, intrusive “scenes,” images real or filmic or dreamlike—a circuit-telling of something too intense and ultimately too extensive to address directly.

At a deeper level, the book operates as lyric because it is implicated in the logic of metaphor, and the relation of metaphor to trauma. “Metaphor is a kind of fiction,” the speaker says early on. “It projects a narrative by projecting it in or on another body. And the body carries on the business.” This idea of two bodies or two selves recurs throughout, both at the shooting scene in which the speaker tweets from hiding, “generat[ing] another version of myself in space, a body that is not my body, a narrative meant for public consumption and interpretation,” and in the long wake of it: “I have not gone outside, not really, at all since then. I send my second body to do what work is necessary, and I stay inside.” But crucially, although the speaker never states the point explicitly, the trauma itself is formed by the way the cyberstalking and murder of estranged wife Christine Belford by her husband’s family echoes the speaker’s own first marriage, which she left eight months after the shooting: “A poet’s job is to speak connections between things not recognizable as facts but which are true.” It is the metaphoric resemblance of the speaker’s body and the murdered woman’s, the twin spaces they occupy, that contributes to the speaker years later “still hiding in a stairwell in a parking garage in Delaware.” Traumatic memory freezes the psyche within a single point which renders the past ongoingly present—and this, too, is an entrapped, nightmare version of the lyric mode, which contemporary critics argue is based on moments that transcend time.

Yet another haunted lyric moment that informs the book, and sets up its recurrent water imagery, is the speaker’s near-drowning as a child:

My instructor wants me to explain how this [the speaker’s inability to put her face in the water] occurred, and I tell him: when I was ten years old, an ocean wave pulled me under, pressed my face into a vortex of sand and water that suddenly seemed bright, like a camera flash . . . like I was being seared into an image, an image that might substitute for me or swallow me alive, and then I felt myself hauled up and returned to the world.

The speaker is not only frozen in the stairwell, but trapped under the water against the sand, another metaphor for the space in which she finds herself. “When I am back in the world again I will explain,” she says in the book’s final sentence. Perhaps there is some hope to be found in the recurrent image of the octopus, which seems to function as a metaphor for the writer, moving by taking in and expelling water and reaching its tentacles toward what it wants.

Despite the tight focus of its immediate subjects the book is always addressing the legacies of the western world and the situation of contemporary America.

What makes Bullet Points so exceptionally rich, however, is that it constantly extends beyond these experiential and psychological dimensions to worry at the interwoven strands of a vast spectrum of historical and legal facts that inform the situation—or, perhaps more accurately, that the speaker grasps at to create structures of comprehension, plausible fictions. These include the origins of Delaware, the legal concepts of incorporation and property rights and how they operate, the history of the farthingale, and the complex relationship between literal and figurative space, women, and colonialism. We understand that the violence against women of which the speaker is a witness is imbricated within the history of violence and capitalism and of men regarding women as property. Of her first husband, the speaker says chillingly, “He does not stand for anything not profitable. A woman is an investment and should be made to pay.” Thus despite the tight focus of its immediate subjects the book is always addressing the legacies of the western world and the situation of contemporary America—and of course the issue of gun violence has never been more urgent. The decade-old shooting feels entirely present, a collective horror we all are trapped in.

As befits its title, Bullet Points does not offer any argument or directive or generalized lament about these matters, which would be the point at which it would risk predictability in some way; its refusal to do so is deeply refreshing, although it keeps readers off-kilter, searching for stable meaning in the text along with the speaker. Ultimately it is her shattered voice we hold to—her erudition and searching intelligence trying and trying to find something to cling to, while at the same time recognizing the fictiveness and futility of the attempt. Does it matter that many sites in Wilmington are named for Queen Christina, and the murdered wife was named Christine? Maybe, maybe not. The voice is lucid and controlled, but hyper-controlled, we come to understand, and restlessly, relentlessly driven—“The resort to a particular sort of voice, one’s stock-in-trade, is sometimes desperate, sometimes automatic.” It can recount events with legalistic precision and neutrality of tone, then abruptly descends into eely undersea horrors. That such a brilliant speaker cannot overcome the effects of what she has witnessed, even over years and with the diligence the book documents as the speaker recounts her struggle to write about the shooting, tells us more about the experience of trauma than any description could. It immerses us, as it were, not in the record of an experience but the experience itself.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop