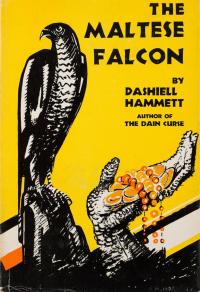

Dashiel Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon: Point of View and Playing with the Poetics of Uncertainty

Typically, in the American, hard-boiled tradition, private eye yarns are told in first person. Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, Ross MacDonald’s Lew Archer, and Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer all tackle blackmailers, family melodrama, and “commies,” respectively, in their own unique voices of sun-drenched romanticism, world weary but empathetic iconoclasm, and Old Testament vengeance. But in The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett presents his golden-age novel in a strange, limited-third perspective.

We’re restricted to Samuel Spade’s movements, but we’re never given direct access to his thoughts. Whereas Marlowe, Archer, and Hammer help decode the world before us, clearing up the cluttered chaos, Hammett keeps us, courtesy of a near, pitch-perfect Hemingway–esque camera objective point of view, on the outside looking in.

We’re restricted to Samuel Spade’s movements, but we’re never given direct access to his thoughts. Whereas Marlowe, Archer, and Hammer help decode the world before us, clearing up the cluttered chaos, Hammett keeps us, courtesy of a near, pitch-perfect Hemingway–esque camera objective point of view, on the outside looking in.

However, Hammett does let us in, occasionally, through brief bursts of filtered meaning, where the novel’s textual intent bends Hemingway’s rules to help guide us.

A look at just the novel’s first eight chapters showcases Hammett’s technique of “limited” filters. Unlike the noun and verb driven prose of Hemingway’s surface reporting, Hammett gives us suggestive guideposts to insights. He also, with regard to dialogue, doesn’t rely as much on “said” constructions to keep emotion under the surface.

Hammett’s brief descriptors are often accompanied by shorthand access to possible meaning. A few examples: “Spade looked at the Lieutenant with yellow-grey eyes that held an almost exaggerated amount of candor”; “The eagerness with which Brigid O’Shaunnesy welcomed Spade suggested that she had not been entirely certain of his coming”; “Spade laughed. His laughter was brief and somewhat bitter”; “Spade was lighting his cigarette. His face was tranquil”; Brigid’s “eyes were wide and dark and earnest”; Joel Cairo’s “embarrassment seemed genuine.”

These “limited” filters remain open to interpretation. Words and phrases such as “held an almost”; “eagerness suggested”; “somewhat bitter”; and “seemed genuine” all provide us readers with clues to “read” the scene unfolding before us, but the qualified commentary leaves us in shadows of uncertainty. Things may not be as they seem.

Hammett’s technique is subtle, an almost hidden form of narrative telling. For example in the very first paragraph Hammett describes Spade as looking “rather pleasantly like a blond satan.” This cues us to be wary, to not fully trust our protagonist, a man who walks a tightrope between morality and amorality. And “pleasantly” is not a word commonly associated with the devil. Just what kind of a hero do we have here?

Moreover, yellow is a through line in the novel, associated with Spade, painting him as a somewhat jaundiced character. Upon hearing of his partner Miles Archer’s murder, Spade responds to Sgt. Tom Polhaus’s claim that Miles must have had his good points with, “‘I guess so,’ Spade agreed in a tone that was utterly meaningless.” Later, that jaundice manifests itself in his body. As Spade seduces Brigid, Hammett revisits the novel’s first image: Spade’s “groping fingers moved over her slim back. His eyes burned yellowly.” Groping? Yellowly? Not words I would associate with an heroic detective. These are markers of an anti-hero.

At the novel’s conclusion, as he turns Brigid over to the police, Hammett again delivers telling judgment: “His mouth smiled and there were smile-wrinkles around his glittering eyes. His mouth was soft, gentle. He said: ‘I’m going to send you over.’” Uncertainty, confusion, resonates in the contrary descriptions. A “soft, gentle” mouth versus “glittering eyes”: a binary of kindness versus allusions to the snake in the Garden casting its glittering spell—

Hammett’s epilogue presents a foil character, secretary Effie Perine, passing final judgment on our anti-hero, positioning us, possibly, within her perspective. Upon hearing of Brigid’s fate, she “escapes” from Sam’s final embrace: “‘Don’t please, don’t touch me,’ she said brokenly. ‘I know—I know you’re right. You’re right. But don’t touch me now—not now.” Hammett’s adverb “brokenly,” something Hemingway eschewed using, colors the novel’s final moments. Her feelings for her boss have changed.

American detective novels are also often about control. How does the hero protect him or herself from the threatening world that surrounds them? Our heroes rely on smart-ass zingers to maintain distance, descriptive judgments on appearances to not get too close to the people they interact with, and alcohol to numb the deadening effects their pyrrhic journeys take them on.

In Hammett’s classic novel, Spade’s dialogue comes across, at times, as somewhat stentorian. He’s always putting his stamp on conversations, closing off further discussion with his brand of truisms. It also allows Hammett, who stays on the outside looking in, a chance to give us some of Spade’s “interiority.” This isn’t so much dialogue as exposition, but dialogue as philosophy.

Spade is a man of so many opinions. Here’s a small catalog of truisms that let us into his thinking and showcase his ability to cutoff and finalize conversation: “You’re good, you’re very good” (concerning Brigid’s deftness with lying); “You don’t have to trust me, anyhow, as long as you can persuade me to trust you”; “I don’t believe you” (in response to more of Brigid’s lying); “The cheaper the crook, the gaudier the patter” (on the ineffectiveness of gunsel, Wilmer Cook); “Everybody has something to conceal”; “I say what I please”; “Bad business to let the killer get away with it—bad all around” (his reasoning—tied into a sense of a moral code—for not letting Brigid get away with killing his partner—even though he disliked his partner immensely); “Don’t be silly, you’re taking the fall.”

The beauty for me in Hammett’s technique is how through this somewhat non-traditional perspective he turns his authorial eye on the detective, making him the specimen under glass, instead of concentrating merely on the characters Spade interacts with. Spade’s desire for controlling the narrative and the world around him gets loosened quite a bit. I’ve already discussed how Effie’s perspective may align with our own in the novel’s epilogue, but perhaps the greatest moment of pushback occurs in the novel’s third and final act.

Spade is paid a thousand dollars by Casper Gutman for finding the Falcon. When Spade counts the money, a hundred dollars is missing. He suspects Brigid of “palming” it, and in a somewhat shocking scene, one that’s not in the John Huston film adaptation, Spade forces her into the bathroom and orders her to strip, to make sure she doesn’t have the money.

Brigid sadly asks Spade, “You won’t take my word for it?” She didn’t palm the money. Spade, forever seeking control, replies, “No. Take your clothes off.” She warns him that to carry out these actions will “kill” something in their relationship. Spade, pushing aside feelings, mutters, “I don’t know anything about that. I’ve got to know what happened to the bill. Take them off.”

What follows is a scene that could have been presented pruriently (like something out of Spillane: “And she was a real blonde!”), or presented within the boundaries of the tyranny of the male gaze, but instead Hammett flips the moment, having us side with Brigid: “She looked at his unblinking yellow-grey eyes. … She removed her clothes swiftly, without fumbling, let them fall down on the floor around her feet. When she was naked she stepped back from her clothing and stood looking at him. In her mien was pride without defiance or embarrassment.”

Brigid is triumphant at this moment. She maintains a certain dignity, a dignity that our anti-hero all too often lacks.

Recommended

A Behind the Scenes Look at Art Selection and Cover Design for the NAR

“Doubling and the Intelligent Mistake in Georges Simenon’s Maigret’s Madwoman”

What the Birds Showed My Wounded Child, My Adaptive Adolescent, & My Wise Adult