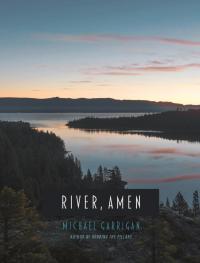

Where All Things Converge: A Review of River, Amen by Michael Garrigan

Toward the end of his life the French philosopher and phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty was working on a phenomenology that would avoid the shortcomings of both idealism and empiricism. Merleau-Ponty sought to craft a philosophy at once embodied but also deeply reflective, a tangible phenomenology that also reached beyond the merely material. Tragically, Merleau-Ponty died from a heart attack before finishing this work; thankfully however, parts of this manuscript were published posthumously as The Visible and the Invisible in 1964.

At the end of the The Visible and the Invisible is a standalone essay entitled “The Intertwining—The Chiasm.” Throughout this essay, Merleau-Ponty sketches out an ontology of flesh—a term he employs to describe that thing which links subject and object, the seer and the seen, the visible and the invisible. Merleau-Ponty envisions flesh as the medium in which these relationships take place and, importantly, points out this linkage is not unidirectional but reversible, two-way, chiasmatic: “Once a body-world relationship is recognized, there is a ramification of my body and a ramification of the world and a correspondence between its inside and my outside, between my inside and its outside.”

At the end of the The Visible and the Invisible is a standalone essay entitled “The Intertwining—The Chiasm.” Throughout this essay, Merleau-Ponty sketches out an ontology of flesh—a term he employs to describe that thing which links subject and object, the seer and the seen, the visible and the invisible. Merleau-Ponty envisions flesh as the medium in which these relationships take place and, importantly, points out this linkage is not unidirectional but reversible, two-way, chiasmatic: “Once a body-world relationship is recognized, there is a ramification of my body and a ramification of the world and a correspondence between its inside and my outside, between my inside and its outside.”

Merleau-Ponty’s concept of flesh constantly came to mind as I read through Michael Garrigan’s most recent book of poetry River, Amen (Wayfarer Books, 2023). Garrigan’s poems cover a variety of themes but throughout is a tenacious wrestling to articulate our relationship to the world around us. And, as does the best ecological writing, Garrigan’s poetry doesn’t simply acknowledge and admire the world but reaches beyond to a place where the work and the writer is not only associated with but affected by the world: “Sometimes I think we are still sitting, smoke/ melding the night to our fingers and lips.” The gaze goes both ways, as does the touch. “I fell in love with this river and this mountain./ I keep coming back, trying to grab a hold.”

•

I evoke Merleau-Ponty for a selfish reason: I don’t want to fall into the traps and cliches most often associated with ecological literature and poetry. While River, Amen covers many familiar environmentally-oriented themes, it would be a disservice to Garrigan—a poet, writer, and teacher from the Pennsylvania region of the Susquehanna River Basin—and a failure on my part. Garrigan’s poems—56 of them stretching over 90 pages—are not simply the lines of one who enjoys the outdoors, but one who has been deeply transformed by the places he inhabits and writes about.

River, Amen carries through a variety of topics: flyfishing, culture, history, landscapes, waterways, flora, fauna, domestic life, religion, ritual, faith, and more. Though many of the poems seem loosely connected at first, an overriding metaphor slowly draws these poems together—the titular river. From the very beginning of the work, Garrison ventures beyond the material into the metaphorical and even spiritual to understand the river as a connection, a force, a place, a god, a song, a thread, a place where all things converge. “Each river becomes a prayer,” the narrator tells us in the opening poem “Creation Story,” reminding us, “The river sings most beautifully/ when you are there to listen.” And yet, the world Garrigan draws us into is not simply Arcadian—it is also a world of ephemerality, of destruction, of death, “Listen before/ all these water songs evaporate.”

Garrigan is a talented poet with a strong sense of rhythm and sound, and a keen eye for description. His lines reverberate with a deep sense of imagery and place, whether he is recounting an evening trip to catch catfish—“We walk the tracks in the dark/ with a six pack and lit Camel Lights/ as flashlights and bug dope, chicken livers/ and sharp hooks jostle in tackle boxes”—or an extended meditation on carps becoming gods “shuffling like stalks of corn in mourning wind” and “taking turns swimming into the deep/ channel to suck down little damselfly nymphs,” as “they dart off into the deep current and your/ palms are left open and once sediment settles/ you consider sliding your whole body into water/ to become a river-prayer-flag forever caught in current.” One gets the sense through this collection that Garrigan can handle the mundane as well as the metaphysical, though he never loses the intimate connection between the two.

River, Amen covers a variety of forms including prose poems, ghazals, haibun, and the songenizio—a form Garrigan and his friend Andrew Jones created based in part on Kim Addonizio’s “sonnenzio.” (Essentially, a songenizio begins with a line from a song and subsequently repeats one word from that line in the following 13 lines, while concluding with a rhyming couplet). While Garrigan deftly handles these forms as well as the more open poems, I found his prose poems to be some of the strongest. They provide a compression that allows Garrigan’s words to sing, an energy that condenses the narrative into a singular, revelatory point that ultimately breaks beyond itself. For instance, the prosey Haibun “Where Eels Spawn Haibun,” which after discussing the discovery of freshwater eels spawning in the Sargasso Sea concludes, “I bet you could find the DNA of every living thing in that sea. Something died, something ate it, something decomposed, water came, washed it to sea. Eels spawn where our deaths lie, bring us back when they return to our rivers.”

Garrigan also takes stock of the many ills humanity has cast upon the natural world in poems like “Coal County Paradise,” “Upon Hearing that Snakehead Catfish Passed through the Conowingo Dam Fish Ladder,” and “Post-Industrial Wilderness, Rejoice!” Whether pollution or the spread of invasive species, the poet reveals the many ways our intertwining with the natural world has become destructive on a scale unimaginable until our industrial present. While Garrigan avoids the moralizing that plagues much environmental poetry, there is a sense that some of these poems strain in their poetic register to handle this topic. As I reflected on this—the way certain lines seemed to falter or struggle, to lose their music—I wondered if this is less a fault of the poet and more the reality of our broken, polluted world: we have to confront the brokenness through and in brokenness.

Religion is another central theme that shows up throughout River, Amen. While Garrigan takes occasional swipes at organized religion, his larger project tends more toward the creative than the critical here. Throughout the collection, poems reenvision ritual and liturgy outside the confines of places of worship and instead along streams where the poet as fly fisher suddenly morphs into a priest of sorts: “I pray in the eddy,/ swirl of psalm/ flotsam of faith/ cast of communion/ genuflection of grace./ Hands clasped, head bowed, eyes closed.” Though the poet is at times “sure of my faith in the unseen” there are also the “times when I only see the water in front of me/ yielding to downstream dams slowly stalling its reaching.” This is the genius of Garrigan’s spiritual vision—the yearning of faith as relationship, somedays we reach, somedays the world does. Regardless, it is never alone, we are always bonded together, “My name is stubborn, a moon listening for the pond’s teaching,/ a horizon holding sound and syllables caught in all this reaching.”

•

Merleau-Ponty intended his conception of flesh to extend out beyond the relations of seer and seen in the natural world. Though he never finished writing about the topic in full, there were notes toward the chiasm’s role in language, art, and philosophy. In poetry, we encounter the world through another’s eyes, and not just the world but the flesh of the world, the relationship between the poet and the world they inhabit. The poet transforms the flesh to word that the reader may turn word back into flesh—another relationship, another chiasm. Reading through River, Amen was a wonderful experience of this entangled richness. As Garrigan intones in the epistolary poem “The Poet Sits on a Ledge and Writes a Letter,” “I am here to tell you, Dear Reader, that the river never stops flowing…There is always a river.”

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop