Sentences and Bodies

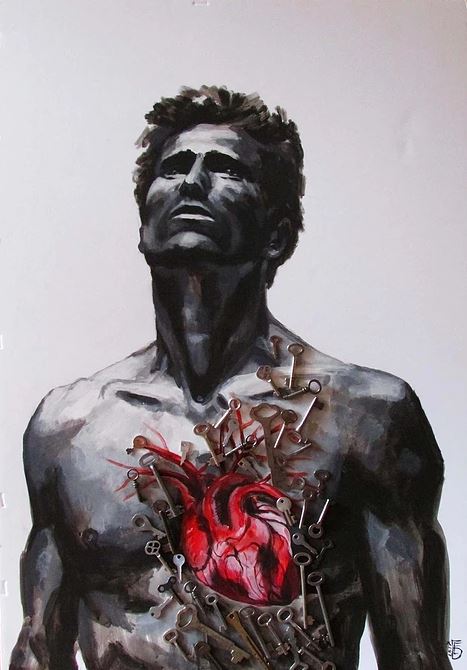

The line as a not necessarily articulate unit of sensation—a breath, a strain of cerebral activity, the muffled speech of a mother vibrating through the womb to reach a fetus—this is more important to my experience of a poem than anything else. I’d venture to say that, as a poem is a felt thing, these visceral elements are most important to comprehension of a poem which, after all (at least when I read) isn’t so much about understanding as it is about engaging, the relinquishing of the expectation of rote comprehension in order to participate in something more elusive and incantatory, poetry of and through the body. Or in the words of William Wenthe, “language is, first of all, of the body.” I think of the nominalism/realism dichotomy, whereon one hand words are fated signifiers, only possible as abstraction to organize the actual world, and on the other hand words become facets of the actual: they come to embody reality. I subscribe to neither, though they are useful in considering the construction of the poem. If words are emitted from the body, transcribed to the page, and ultimately received by a body, isn’t the transaction a physical one, regardless of what substance the words themselves are? And isn’t the transference of the physical experience dictated by the particular structures and choices made in the organization of the words, the mechanics of the poem? I imagine now a conference of the nominalistic/realistic where theres an agreement of dual engagement with something less discernibly dichotic happening in that middle stage between bodies: kinesthesis above physics, with the reification of signs in the physiology of a body.

I carry a Rainer Maria Rilke poem around with my in my wallet, one of the more overtly religious ones that he wrote when he was younger than I am now, but not than I was when I first jotted it down and folded it behind my driver's license. I remember how important it was that I transcribed the line breaks correctly, that even after my dad read it aloud to me and it was clear the words themselves would linger in my psyche, and probably in his voice, I wanted it the way it was supposed to be, the way it could be adopted into my own voice every time I returned to it, to the shape of it. I almost want the silhouette more that the words themselves, and it’s still what I look for when I unfold that browning paper. The vibrations that shape will offer to my trachea and chest, the breathes I will have to distribute throughout.

A professor once admitted to me that she’d given up reading for content, that she derives understanding from the shape and general movement of texts. The minute things fall in later, organically. Maybe it’s because this is a space I’ve lately been occupying, but it feels right for the comprehension of 'texts' generally, and in the context of poetry, felt text: reading with the body. A glaring omission, though, with that concept, is particular attention to language. This, to me, is also of crucial importance. If it’s shape and movement that facilitate this physical transference of the line, where are the individual words and their relationship to one another experienced? How, sonically and aesthetically (and nominally) do these minute units affect themselves from and into and through the body? That’s interesting to consider, particularly in the Rilke case, because I notice each time how God is there, and how that, unlike it often does, doesn’t disconcert me:

God speaks to each of us as he makes us.

Then walks with us silently out of the night.

These are the words we dimly hear:

You, sent out beyond your recall,

go to the limits of your longing.

There’s also a litany of other things about the particular language of the poem, and this passage in particular, that are so important to me: the clipped, declarative sentences. The quiet authority. The plainness of the vocabulary that feels incomprehensibly rich. The words themselves are important, of course they are—they’re both the signifiers and the stuff itself! Dually vibrating. I’m certain I don’t understand any of this, and I’m certain it’s more important to me because of that, but I do know that my body has been permanently and perpetually affected, and that there are lots of bodies.

Notes:

William Wenthe’s essay “The Craft of Thought: The Sentence in Contemporary Poetry” is quoted here, and his argument about sensation in poetry is paraphrased.

The Rainer Maria Rilke poem is “Go to the Limits of Your Longing”, translated by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop