Speak, Dog, Speak

Our first interview went something like this.

“So, what can you tell me about being a dog?”

Cici, my 14-pound mutt, remained mum.

“Not talking, eh?”

She cocked her head in confirmation.

It was a rare moment for us, not the “me-talking-to-a-dog”part (that’s standard practice these days), but her refusal to offer so much as a bark in reply. For the eight years we’ve known each other, my Chihuahua/spaniel/[insert your best guess here] mix-breed had always excelled in her loquaciousness—just ask our mail carrier. But now that we were getting down to  brass tacks—now that I actually wanted to hear her speak—she apparently had nothing to say.

brass tacks—now that I actually wanted to hear her speak—she apparently had nothing to say.

“Come on,” I coaxed, “I’m trying to write a book about you. You got nothing?”

She demurred with the cool confidence of a cat.

And so began my journey in writing From The Mouths of Dogs: What Our Pets Teach Us About Life, Death, and Being Human (University of Nebraska Press, 2015). While my pet “interviews” gleaned few insights, my interactions with the animals themselves—not to mention their human counterparts—revealed to me an array of life lessons, all of which I’ve taken to heart. Simply put, the pets took me to places I’d never been before, prompting me to view our world through a different lens.

And while that all sounds well and good, trust me, it wasn’t all belly rubs and slobbery kisses.

While indeed there was no shortage of either, writing this book also forced me to confront an array of difficult issues within the pet world—from animal abuse, to animal shelter euthanasia, to the grief we feel when forced to say goodbye to our four-legged brethren.

Let me be clear: I, too, have had a little trouble saying goodbye.

So much trouble, in fact, that over two decades after the death of my childhood dog, Sandy, her ashes could still be found on a backroom bookshelf. It wasn’t until I began writing this book that I began to ask myself why.

Why has my family never gotten around to giving Sandy a proper burial? I wondered. What good are her ashes alongside a

row of Norton anthologies?

The truth, as I eventually conceded, was that we hadn’t buried her because we weren’t yet ready to let her go. For me, the finality of the act signaled a death of another sort: confirmation of the end of my childhood. Though one might think 31 rounds of blowing out birthday candles might also have clued me in to my transition to adulthood, for me, Sandy’s ashes always served as tangible proof to the contrary. Sandy, after all, was a direct link to my early years. She was the one who clip-clopped alongside me as I took my first wobbly steps, the one who kept me warmer than my bed sheets, and the one who—through her own death—would teach me how to grieve.

As Cici grows a bit gray beneath the muzzle, I can’t help but wonder if, she, too, has lessons to offer my own children. After all, over the years she’s done her own fair share of clip-clopping alongside youngsters and warming us beneath our sheets. The trouble, of course, is that we enjoy her company so much that none of us are the least bit ready to consider the last lesson she has to offer. That is, none of us wants to face the fact that Cici’s death is not an “if” but a “when”.

I remember all too well the last time I patted Sandy goodbye before starting toward the bus. How she bowed her head as if bashful as I lifted myself up from the ground. But what I’ve never considered is what it must’ve been like to lift Sandy—now wobbly-kneed herself—into the front seat of the car and drive her to the veterinarian’s office. And until recently, I’ve never considered what it will one day be like for me to do the same.

At the conclusion of my last “interview” with Cici, I gave it to her straight. Told her that if indeed we are destined to make that last, fateful drive together, then I’ll find the courage to do it.

“But not before giving you the best, last day I can,” I promised. “All the canned food you can eat.”

You can only pet a dog so hard for so long before eventually that dog walks away.

Which Cici does after fifteen minutes or so, turning tail and leaving me to my lesson.

Illustrations:

First impressions by Jessica Mercado. Jessica Mercado is a New York based illustrator who enjoys delving into the relationships between people, and is fascinated about how people can affect one another. She uses metaphors, lighting, color, and composition to create mood and meaning between her characters’ interactions. Jessica has earned her BFA in illustration from Parsons the New School for Design.

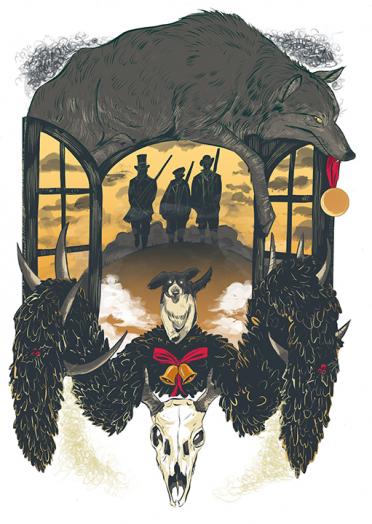

Beasts and Superbeasts by Ryan Inzana. Ryan Inzana is an illustrator and comic artist whose work has appeared in numerous magazines, ad campaigns, books and various other media all over the world. His graphic novel Ichiro was the honor selection for the Asian/Pacific American award for young adult literature and was also nominated for an Eisner.

Title unknown is part of a series, The Things About Being Alive by Robin Richardson. Robin Richardson is the author of Knife Throwing Through Self-Hypnosis, Grunt of the Minotaur, and is working on her latest collection, Sit How You Want. Her work has been shortlisted for the Walrus Poetry Prize, CBC Poetry Award, LemonHound Poetry Prize, and ReLit Award and has won the John B. Santoianni Award the Joan T.Baldwin Award. Her work has appeared in many journals including Tin House, Arc, and Hazlitt of Random House. She holds an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence and resides in Toronto.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop