The Story as Essay: Or, What I’ve Accidentally Learned by Teaching Comp

About ten years ago I wanted to write an article about how writers, who often teach composition courses, are the last people on Earth who should be teaching composition courses. I had good arguments: First of all, it’s hard for writers to understand and communicate with people who so dislike writing that they only take a writing class when it’s required, and, second, we don’t spend as much time thinking about grammar as administrators might like. Above all, I thought, people who write stories and poems don’t necessarily have all that much to say about the very particular kind of stuff that gets written in these classes—argumentative essays, mainly—because those essays are so far removed from what we do.

Well, nobody wanted my article; magazine editors didn’t see the same problems that I did. They told me that writers get a lot, in fact, out of teaching composition courses. Naturally, this made me feel sulky and misunderstood.

Ten years later, I can say they were right.

Of course, there are the obvious benefits—the pleasures of learning how to articulate what we know about writing, of being pushed to think in new ways, and of kindling real interest in writing among students who aren’t expecting to like it. In general, I have found teaching to be good for the mind and for the soul, and comp means encountering students and ideas that I wouldn’t encounter otherwise. But there’s also been an effect I never would have expected: teaching the argumentative essay has changed the way I write short stories.

I mean, I should have seen it coming. I’m constantly telling my students how their papers need to be like short stories, how those papers need to have (like a good short story) precise detail, a compelling voice, obstacles, and suspense. So I already knew that short fiction could teach us about how to write essays. Why should it surprise me that the connection goes both ways? If an essay can have plot (will the author turn out to be convincing, or not?), why can’t a short story have arguments?

Indeed it can; in fact, without even intending to, I have found myself writing some stories that actually resemble the argumentative essay.

The signs are subtle in my story, “Our Mothers Left Us,” which doesn’t offer an argument, exactly, but which, like the essay, uses each paragraph to make a separate point. In a typical short story, individual beats/scenes are broken into a number of different paragraphs, including lines of dialogue and actions and so on. In “Our Mothers Left Us,” on the other hand, I move chronologically from one thing to the next, and each time there’s a new beat in the narrative, it gets its own single paragraph. In one paragraph, the mothers disappear; in the next the kids search for them; in the next the fathers become involved; et cetera. The story accumulates in clear, distinct steps, which is an ideal (for essays) that I harp on in class.

My story, “We’ll Finish When We’re Done,” operates in a similar way. In this case there’s dialogue, and lots of paragraph breaks in this one continuous scene—but the story, about a surprisingly enthusiastic barber, builds (just the way I teach my students to do it) point by point. First he gives the customer a trim, and then a more drastic cut, and then a military buzz, and then he shaves him bald. Step by step, the cut gets closer—believe it or not, it gets closer than bald—just the way an essay gets closer and closer to the vindication of its thesis.

And then there are the stories I’ve written that don’t just resemble the form of arguments but instead actually become arguments. In “The Guy We Didn’t Invite to the Orgy,” the speaker—a collective voice—tries to explain why the group didn’t invite this one guy to the orgy they just had. In a sense it’s a backward argument, because the speaker rejects (rather than advancing) one argument after the next—specifically, it isn’t that the guy is prudish, or bad in bed, or unattractive, or a bad guy. In fact, he’s great in all those respects. And so the story is resisting the final impulse to become an essay; it’s trying to fail to explain what happened, by trying not to embrace a thesis. And yet, I have to admit: by the end of the story, an explanation—a thesis—creeps in anyway. I won’t include the spoiler here, but suffice it to say that the power of the argumentative essay is inexorable.

What I never expected was that this power would come to shape my fiction-writing. And yet I’ve already written a handful of argument stories—not just these but others, like “Nobody Else Gets to Be Crazy When You’re Being Crazy” and “Counterfactual”—and I assume that there will be more of them. These stories will have their place. It’s good, in fact, for a writer to try on new forms—the short-short, the letter, the recipe, the instruction manual, and (why not?) the argument.

At the same time, I do worry a little: if I spend more and more time thinking about students’ composition papers, will more and more of my stories end up neat and orderly and driving to a point? Will I stop developing characters and plots in complicated and uneven ways—in organic ways—and instead only move things forward in discrete, distinct units?

Which brings me to the point of this essay. Because there’s another thing I’m always telling my students: if you can become conscious of your writing habits, good and bad, then you will have some power over them. In other words, it’s one thing to try on a form, to use it as a tool when you need it, and it’s another thing to have it sneak up on you and use you. That’s why you need to pay attention to your writing. And I’m hoping that this little bit of attention-giving (i.e., the attention I’m giving it by writing about it right here) will help me turn this form into a choice instead of an inevitability.

These days, I wouldn’t claim that teaching composition is such a bad gig for a writer. In fact, I like it a lot. But maybe it’s time to start teaching something else. Math? Genetics? Business? Music composition? After all, I could be writing stories and poems in the form of quadratic equations, DNA sequences, earnings reports, or arias. What you learn by teaching forms—any and all forms—is that there is an orgy of possibilities out there, and that you are definitely invited.

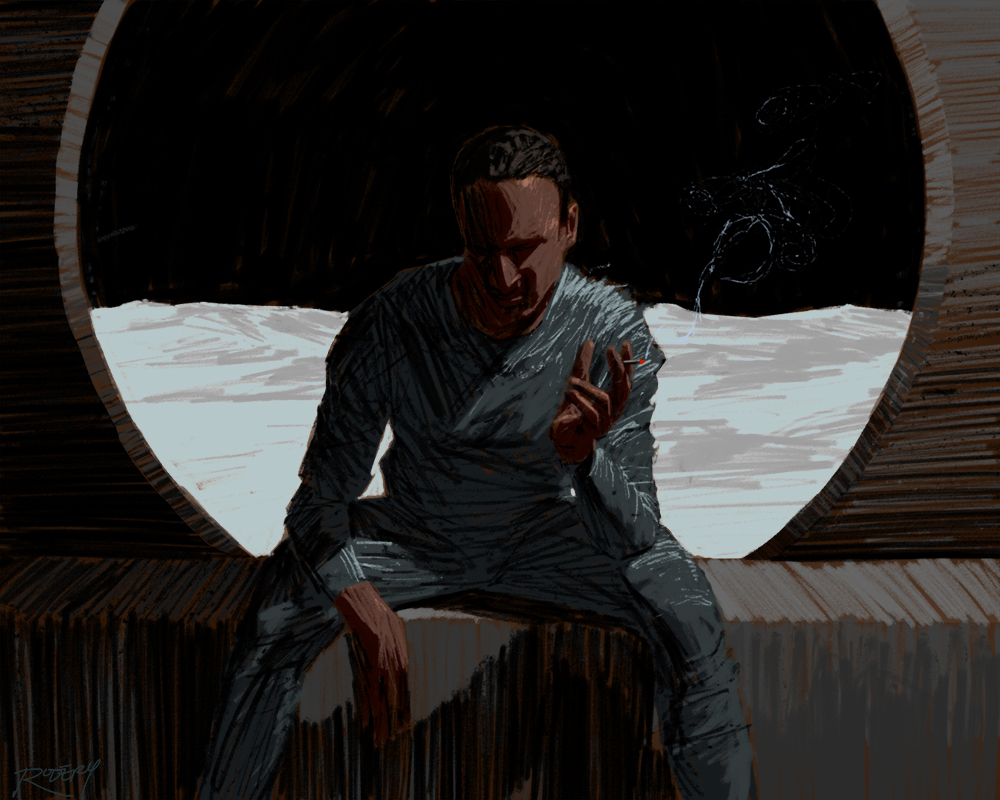

Illustrations by Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Clay’s illustrations have been featured in the North American Review, most recently in issue 299.4, Fall 2014.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop