Things I Wish I'd Said: A Tribute to the Poet Dick Allen

Last year, on Christmas Day, the poet Dick Allen passed away. The author of nine books of poetry and a former Poet Laureate of Connecticut, Dick was a formidable presence in American literature.

It was fitting that he died on Christmas, a day of birth. He would have appreciated the cyclical implication of that. His last published book was titled Zen Master Poems, which was inspired by his interest in Buddhist mysticism.

Dick and I never met in person. For years, were friends in a way that has long been out of style—we wrote to each other. Dick and I first began writing in 2013, when my poem, “When the Men Go Off to War” appeared on the site Verse Daily. I was a brand new poet then, with only a handful of publications. It is a testament to the kind of man Dick was that, as a celebrated seventy-four-year-old poet, he wrote to me, a twenty-eight-year-old young writer no one had ever heard of, to tell me how much he had enjoyed my work.

How to explain what that note meant? We began communicating every month by email. He wrote long, elegant notes, musings on family, writing and philosophy. He would encourage me by sharing his own difficulties with writing and publication. The struggles, it seemed, went on, and in a way it made me feel less alone, that somewhere Dick was at his own desk, worrying about the same things I was.

Dick was the recipient of many prizes, but perhaps his most enduring work was the poem, “Solace,” that he wrote for the victims of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting. “Incredible how we laughed and cried,” he wrote, in the simplicity that defined his style, “in the snow lightly falling.” It was later set to music by the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer William Bolcolm and has been performed many times. Dick, of course, never mentioned this to me; he wouldn’t have. He never wrote of his achievements, except to finally share the news of the publication of his last book, of which he was very proud.

I learned of his death because I sent a dinosaur to Dick’s five-year-old grandson, Lincoln. His wife Lori emailed me to let me know that it had arrived, but that Dick was not there to see it, at least not in the physical sense. I was in my house in Virginia, giving my three and four-year-old daughters a bath. They were screaming because I had just told them I had to wash their hair. I checked my phone and saw Lori’s email. I was speechless; Dick had just written to me the week before. It was not the email of a man saying goodbye. He began with a joke about my name reminding him of Vicks Vapor Rub.

I remember looking at my daughters screaming in the bathtub, and suddenly they were beautiful. I saw how one day they would be sitting on the bathroom floor watching their own children, and I would be somewhere else. After their bath, by coincidence, a children’s book arrived in the mail—Here You Are, by Oliver Jeffers. “Things can sometimes move slowly here on Earth,” I read out loud to my daughters that evening. “More often, though, they move quickly, so use your time well. It will be gone before you know it.” I thought that was probably Dick, “looking down through the glass-bottom boats of heaven,” as Billy Collins once wrote, sending one last bit of wisdom.

There were things I wish I had said to Dick in that last email, the week he passed away. Instead I was rushed, busy; I wished him a happy new year and said I would write more soon. There is always, it seems, more we wish we’d said. So I am saying it now: Dick, you were a man of many legacies. You were a husband, a father, a grandfather. You were a beautiful writer; your work moved people. You were a good man. And, although it pales in comparison to all those things, you were my friend. And that was something to me.

In his last email, Dick mentioned a journal he had appeared in, many years ago. The last thing he ever wrote to me was, “I’m young there, too.”

Wherever you are now, Dick, you are young there, too.

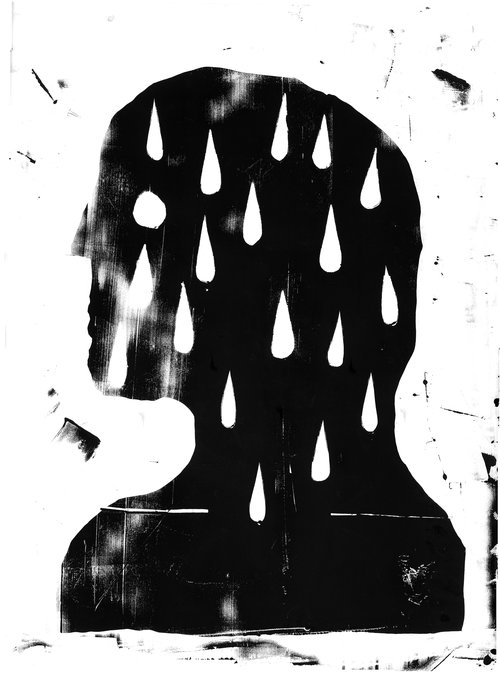

Illustration by: Daniel Zender. Daniel Zender is an artist, living and working in Brooklyn, NY, whose work includes editorial and commercial illustration, graphic design, cartooning, printmaking, painting, and sculpture. He is the recipient of silver and gold medals from the Society of Illustrators and the Art Directors Club Young Guns award. Clients include the New York Times, New Yorker, Nike, Adidas, Facebook, and Google, as well as editorial and commercial work from a variety of clients. He also teaches at Queens College. If you are interested in commissioning or purchasing work, please email daniel@danielzender.com

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop