Why We Need Description

Most of us have two eyes. And with those two eyes we see things that others see. But

because my eyes are different from yours and hers and his, nothing we see can ever be seen the

same way.

To make matters worse, when we try to communicate what we see, the reality we try to capture is never accurate. It can’t be. It’s impossible to see something and communicate exactly what we see because the words we use to describe an image are just, well, words. Take the human hand for example. I can describe a hand by using words like smooth, soft, stubby-fingered, calloused, etc., but those words are merely labels—intangible labels—that we try to apply to something in the physical world.

So there you are, trying to describe an object or a scene or a feeling with words that have

no physical existence in a physical world. You’re bound to fail. And if that’s not foggy enough,

in walks someone else to try to do the same thing, describe that object or scene or feeling. But

wait. Your eyes are different and, therefore, you will see things differently. Your impossible

mission just got worse.

The secret to descriptive writing is that there is no secret. You can only hope to capture a

fraction of the reality you experience. We do that with sensory details, describing the physical

world (sometimes figuratively), while relying on dominant impressions, those invisible vibes

we get from a particular experience. We want the reader to see what we see, taste what we taste,

hear what we hear, etc. So we rely on the words we’ve learned throughout life to convey those

sensory details: His boots crunched through the snow is a lot different than He walked through the

snow. In the former, I see “boots” and I hear “crunching”—two details that second sentence

lacks. Again, this helps the reader get a better idea of what you see and what you are trying to

make him or her see. Consider this sentence about eating: We inhaled our cereal, knowing we would be late for school once again. The figurative “inhaled” (unless the cereal was actually breathed in) expresses the speed at which the cereal was eaten, but it doesn’t descriptively paint the picture, like this: We shoveled the cereal into our mouths and, without swallowing, inhaled the next bite with a continuous spoon-to-bowl-to-mouth motion. Only the sense of sight is used here, but at least a clearer picture is provided with the description of the physical action in the second sentence.

Be careful. It’s possible to describe too much. Your reader doesn’t need to see, hear, or

touch everything you do. The doorknob to your apartment doesn’t need to be described as a

smooth, brass knob, cold to the touch. Just open the door, please. And The way the wheels of the car slipped across the loose gravel isn’t necessary either, unless a description of that scene is absolutely significant to the purpose of your writing (a car crash, perhaps). Once, a student of mine wrote a personal essay about visiting his mom in the hospital after she was diagnosed with cancer. In the essay, he filled an entire paragraph about the floral design on a box of tissues in the hospital room. Because he couldn’t bear to look at his mom, he focused on the looping green vines and the curling tips of the white flowers—a typical decorative box of tissues but a significant object in this particular setting.

The bottom line is to make connections. As a writer, you want to connect to your reader. After all, it’s the primary purpose of writing: I have something to say and I want you to hear it. The more carefully and meaningfully we communicate with our words, the better connection we

make. We’ll never be able to know exactly what someone else sees and how he or she sees it. (Is

that dress on the Internet white and gold or blue and black?) But thanks to descriptive writing,

we can make valid attempts to communicate and connect with our readers, even if we fail to

depict, with words, the reality our senses perceive.

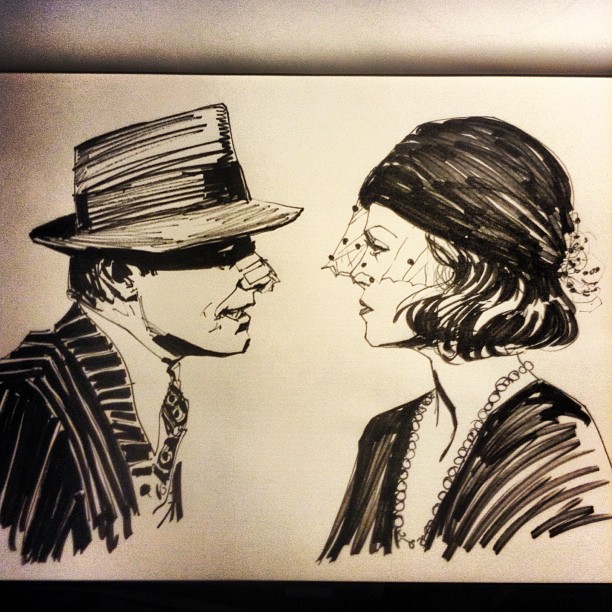

Illustrations by Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Clay’s illustrations have been featured in the North American Review issues 298.4, 299.1, 299.3 and most recently 299.4, Fall 2014.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop