"This is Like Writing"

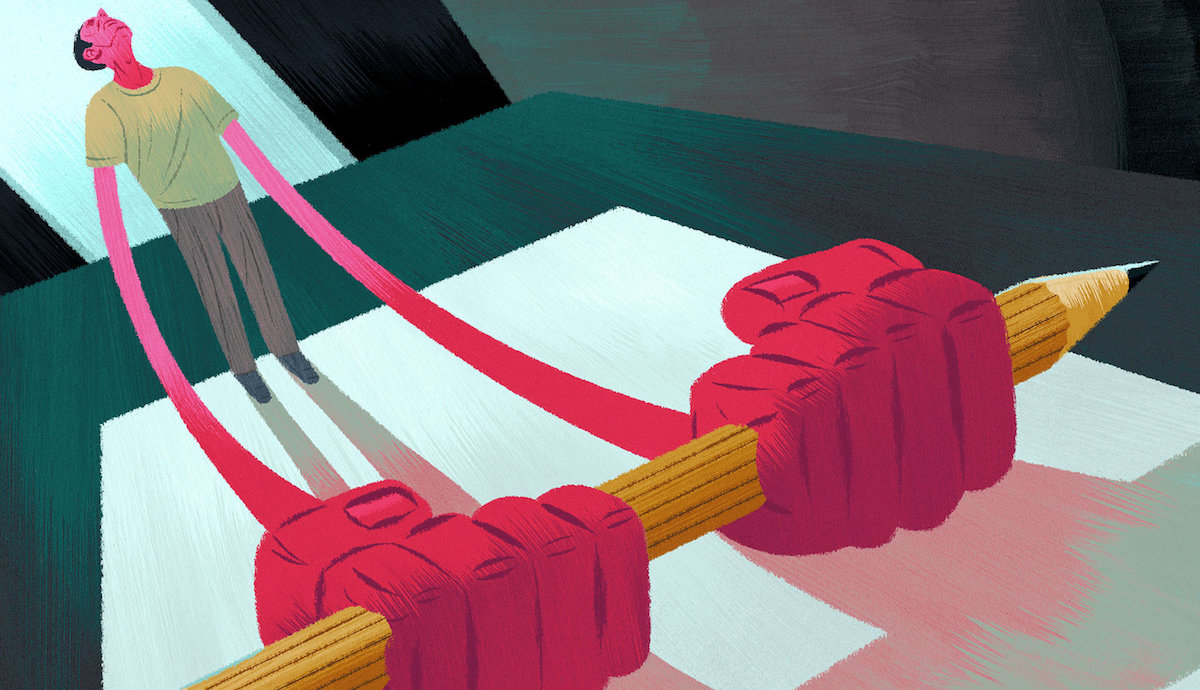

I’ve never cared for essays that compare the act of writing to some other activity. For example: “Writing is like swimming.” Or “Writing is like mushroom hunting.” Or “Writing is like wrestling.” I’ve seen all sorts of attempts over the years to box writing up into a convenient metaphor. But to what end? It might be useful in a freshman poetry workshop, but a seasoned writer can only take solace in such similes when they are incapable of or unwilling to write anything they’re happy with. If I can think of writing in terms of some other activity, then I can justify treating the act of writing in the same way I treat that activity. For instance, I only swim when I am at the pool; analogously, I only write when I am in the place where I regularly write (even if that “place” is a state of mind). Or, in the instance of mushroom hunting, I fumble about in the woods alone until I stumble upon a well-preserved morel sticking out of the foliage. In this case, the act of finding the mushroom is that Eureka! moment of stumbling upon an idea—a poem, a story, an essay—so good that it feels like it has been there all along. Of the three examples I gave, wrestling might be the most accurate. As Yeats said, “[O]ut of the quarrel with ourself we make poetry.” But to merely call it “wrestling” does not do the fight with the self justice. Believe it or not, wrangling an idea into submission is harder than pinning down Andre the Giant.

But these ideas, contrary to popular belief, are not hard to come by. Good ideas, yes, are hard to find. Those stories that write themselves, that come in one vivid, sweeping rush, flooding the brain so fast the fingers can barely keep up, those happen maybe once every ten years. And even then, it’s hard not to buff and polish them through revision later on. But, in most instances, a piece of good writing started out as a piece of bad writing. More than that for me, in fact, an idea may have started out as a sentence—no, a fragment, even—that I thought I’d never see again. Perhaps it was scrawled on the back of a receipt and stuffed in my pocket, only to be retrieved, years later, with the original ink so faded I can’t even see what it is I purchased, but there, on the back, is that mess of words that mean absolutely nothing to anyone but me. Something like “Burt Bacharach backscratcher.” Suddenly a hypodermic rush of familiar sights, sounds, and smells transports me back to a moment alive with stories—some day when I was feeling hopeful about my ability to write. And there he is in my mind’s eye: that homeless guy who looked like Burt Bacharach, scratching his back on the cornerstones of a city bank. It’s the central image in a story I still haven’t written, but there it is, waiting to be snatched up, waiting to be fixed to the page inside a story or poem.

There is nothing like being whisked back to a moment through a piece of writing, especially if it is just a brief, haphazard scrap of an idea like that. When a moment strikes me as profound, it motivates me to find the linguistic tools (in other words, words) to share that experience with others. And even if it doesn’t become something profound, at least it freighted me back to a time I once thought worthy of remembering.

No one ever says, “This is just like writing.” And for the right reason. I do not adhere to the idea that writing is like anything. Writing is the means through which the self is transported. If writing is like anything, it’s a metaphor for the self—a stand-in for that part of being that escapes a name.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop