Writing Spaces

It is 3 am, and I am awakened by a hissing of wind. The stillness feels like what the inside of a coffin would feel like, the darkness draping outside, punctuated by a silence of stars. I have just dreamt about exorbitant amounts of food and tidal waves, somewhere in a dilapidated community, to which I somehow belong. I want to write.

It is 3 am, and I am awakened by a hissing of wind. The stillness feels like what the inside of a coffin would feel like, the darkness draping outside, punctuated by a silence of stars. I have just dreamt about exorbitant amounts of food and tidal waves, somewhere in a dilapidated community, to which I somehow belong. I want to write.

Years ago, prior to my marriage to the poet Joe Weil, my sleep schedules shifted—varied according to the circadian rhythms of my writing. I wrote whenever the “Spiritus Mundi” required that I do so. I existed amongst a whirlwind of constant musing: sleeping, writing, sleeping, emerging briefly into the world, writing.

Soon after Joe and I were married, I gave birth to two children, both of whom have been diagnosed with autism. The schedules of the concrete world demanded that my mind be reoriented to other tasks and concerns.

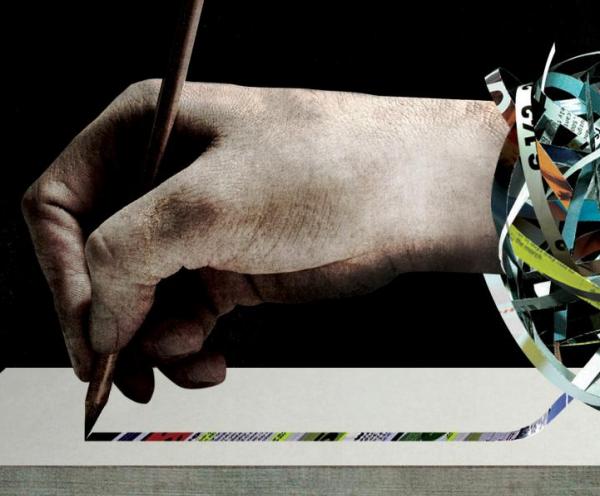

I find “time” to write these days in between the tasks of daily living. And when I do get the chance to write, it’s as though I can breathe again—like an infant slapped into life.

I would say the topics of my writing have changed a great deal—from the bleeding jugulars of unrequited love, to marriage and children. My muses are primarily my children. I like my writing better now. Although I no longer have the luxury of writing whenever I am moved to do so, I think the writing has inherited a certain sanctity and ceremony.

Environment and circumstance have become critical in the forming of my thoughts. Since Joe and I often travel for readings, I have come to love writing in hotel rooms. At home, the whole family has to be asleep, or the kids have to be at school, or everyone has to be quietly playing. I am also not a writer that can write with distractions present, such as a television, music, or the disorganized noise of conversation. And today, with our society being contingent upon constant distraction, it’s a wonder that anyone can write.

I have come to know that the “writing space” is of critical importance. This isn’t true for all writers, but for me, conditions have to be conducive to the flow of words.

There needs to be a distancing from that which I love and which inspires me to write, in order that I can gain perspective on it. That way I can recall experience and image in my working memory, rather than write in the midst of something that I don’t have time or space to reflect upon and think about. I love my husband and my kids—and all three of them are the reason I write. But when I am struck with inspiration, I want to tell them to go to the park. Go to the park and then come home and read my poem. You will know I love you through these acts of language—these acts which necessitate my survival.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop