Buy this Issue

Never miss

a thing.

Subscribe

today.

We publish all

forms of creativity.

We like stories that start quickly

and have a strong narrative.

We appreciate when an essay

moves beyond the personal to

tell us something new about

the world.

Subscribe

From the Editors

It’s on America’s tortured brow

That Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow

—David Bowie, “Life on Mars?”

NASA’s aptly named rover Perseverance touched down at the Octavia E. Butler Landing site on Mars earlier this year, launching a small robotic helicopter called Ingenuity. It was the very first powered, controlled flight on another planet. Ever since the discovery of “canals” on its surface in 1877 by the astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli,

we have been fascinated by the possibility of life existing on our planetary neighbor. Even in the pages of the North American Review in 1913, Edmund Ferrier speculated “What Is Life on Mars Like?” complaining that “Most scientific men deny that they allow any interference of imagination in their scientific work.” In using his own “scientific imagination,” Ferrier concluded, “Mars is certainly inhabited.” Now we can watch 3D videos at our leisure and study hundreds of high-resolution photos of the (literally) otherworldly landscape, a ghostly panorama of red dirt and wind-carved rocks in an ancient river delta, a place we have never occupied in person but that has occupied our dreams for generations. Even if no evidence of life is discovered there, however, Mars remains inhabited—by us.

It’s not hard to celebrate NASA’s monumental achievements—especially as a welcome distraction from the ongoing darkness roiling here on Earth, where it is still necessary to say Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate—but it’s also good to be reminded of the twin human virtues of perseverance and ingenuity, the hedgehog and the fox working together, each improved by collaboration with the other’s talent. We’ve all been required to persevere through a deadly, isolating pandemic, and ingenuity has allowed for the miraculously rapid development of multiple effective vaccines, for which we are thankful to breathe just a little bit easier.

The technological marvel of the Mars mission wakes something in our souls, something that is always grasping after the deep mystery of the universe: the beautiful, the awful, the wonderful, the terrifying. To be sure, space exploration is a scientific endeavor, but it is also an aesthetic one, and so NASA’s question is David Bowie’s: “Is there life on Mars?” In the song, the girl is not just trying to escape into an unrealistic sci-fi fantasy. Rather, her problem is that all of the art she observes around her has either lapsed into cliché (“But the film is a saddening bore / For she’s lived it ten times or more”) or worships at the profane altar of commercialism (“Now the workers have struck for fame / ’Cause Lennon’s on sale again”).

You, dear reader, are Bowie’s “girl with the mousy hair,” too, if you long for art that dares to ask questions about the deep mystery of the universe and to offer in cupped hands the gift of its strange beauty. “True beauty is not pretty,” writes J. F. Martel in his insightful 2015 manifesto Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice. “It is a tear in the façade of the everyday, a sudden revelation of the forces seething beneath the surface of things.” Each poem, story, essay, and piece of visual art you will find in these pages tears at our everyday surfaces, hoping to reveal at least a sliver of a glimpse of the real moon glowing behind the mythical paper one.

The NAR bids farewell to a great friend and supporter—and someone keenly attuned to true beauty—in Jim Wohlpart, who is leaving his position as Provost here at the University of Northern Iowa to become President at Central Washington University. In addition to reconnecting us with Terry Tempest Williams, he helped to make our 2019 writing conference possible. Like his book Walking in the Land of Many Gods, Jim operates out of genuine awe and wonder at the creative force animating the cosmos. “All humans,” he writes, “like all animate and less-than-animate beings, have the potential to participate in this creative force.” And we’re lucky to have participated alongside Jim for the past six years. Though he will be gone, he will not be gone. As the Indian poet Basavanna says, “things standing shall fall, / but the moving ever shall stay.”

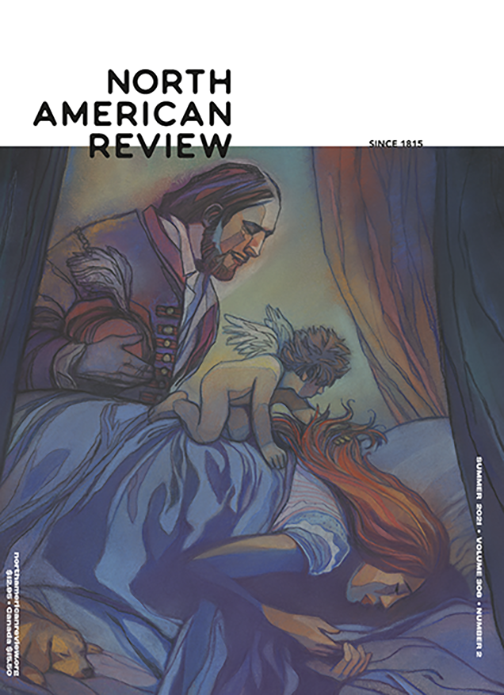

On our cover, Gary Kelley’s Sleeping Beauty is not one you’ll recongize from Disney but from Charles Perrault’s version of the tale, transforming the good fairy (“le bonne Fée”) into a daemon-like putto, who gives her the pleasure of pleasant dreams (“le plaisir des songes agréables”). Nor will you mistake Gina Ochsner’s “Snow Queen” for Disney’s Frozen. Kij Johnson selected this contemporary retelling of Hans Christian Andersens’s original tale as the winner of the Kurt Vonnegut Speculative Fiction Prize. Both narratives are re-enchanted in the able hands of these attentive artists, and in turn they re-enchant the world for us, unlike Mickey Mouse, who “has grown up a cow” and forgotten the keys to the Magic Kingdom.

Disenchantment is not inevitable. We can (and must) unfurrow our tortured brow and ask the earnest aesthetic question: “Is there life on Mars?” After all, Beauty, though cursed to die, was also destined to dream—and eventually, to wake up. ⬤