A Review of Sharon Hashimoto's "More American"

Seattle poet Sharon Hashimoto provokingly titles her new collection “More American” (Off the Grid Press, 2021). Is it desirable to be More American? Less American? Most American? All American? Ugly American? Red-blooded American? True American? One label applied to many Americans is that of Never American. Their ethnicity, that is, being not White American, is evident by their faces, demeanor, and family culture.

Seattle poet Sharon Hashimoto provokingly titles her new collection “More American” (Off the Grid Press, 2021). Is it desirable to be More American? Less American? Most American? All American? Ugly American? Red-blooded American? True American? One label applied to many Americans is that of Never American. Their ethnicity, that is, being not White American, is evident by their faces, demeanor, and family culture.

In Hashimoto’s work, poem to poem, the definition of More American deepens as it reaches into memories to define the generations of Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans in the USA’s Northwest and Hawaiʻi. So definitive is the particular experience of each successive generation, the groups have earned distinctive names. Generally, each of her book’s four sections concerns these generations: Issei (immigrant), Nisei (WWII), Sansei (Post-WWII / Hashimoto’s generation), Yonsei (fourth generation), and the more inclusive Nikkei (being of Japanese heritage).

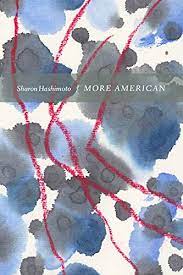

“More American’s” cover art reinforces that Hashimoto’s poems concern incisive content. Artist Alan Lau is a West Coast-born Chinese American. In oil pastels, four red lines strike across a background of watery blue pools rendered in Sumi ink and watercolor. “More American” won the 2021 Off the Grid Poetry Prize and the 2022 Washington State Book Award for Poetry.

Hashimoto’s poems are crafted with words, lines, and stanzas effectively composed. As an author of both poetry and short stories, she brings fiction skills to her poems. However, her poems are not narratives. Like a classic short story, each poem builds tension. All images and dialogue aptly serve this tension. Shifting poem to poem, the point of view secures the poems clearly in the landscape of being Japanese American. Hashimoto never rants or shames. It’s the memories that deliver. Readers enter poems that elicit understanding, empathy, and knowledge of what it is to be human and to be a family living in a country that uses a color wheel to rate worthiness and to determine justice among its ethnic minorities.

The title for the book’s Part I, “Japanese-American Dictionary,” results from Hashimoto’s adjustment to growing up in a dual-language family. She doesn’t speak Japanese but knows maybe five hundred Japanese words that mostly deal with food. For generations of immigrant families and most Americans, food is the entry into an ethnic culture through eating at restaurants or friends’ homes.

In the opening poem “Oriental Flavors,” an adult remembers her grandmother’s mimeographed cookbook and the handwritten notes her mother made in its margins. The speaker concludes, “I search for the way / Grandma stuffed rice into wrinkled skins of age.” Most recipes give the ingredients and instructions. Marginal notes help, but missing is the cultural handwork showing how to insert the rice into the deep-fried bean cake. The speaker, a third-generation granddaughter, now has only a memory of how to do it right. Many Americans prepare old family recipes but try to remember what can’t be written: how ripe a fig should be, how to tip the skillet filled with batter, or how much is a pinch of salt, really.

In Part II “The War,” the poems detail the tribulations of those of Japanese descent during WWII. In the poem, “August 9th,” the US government dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The cataclysm engulfed members of immediate families of Japanese immigrants in America. The poem describes the bomb’s obliteration of family members’ bodies and sanity: “Children sat hunched under broken / umbrellas, rocking themselves,” and “Where would fireflies go? / X-rays couldn’t find them. / Yanking on a barren branch, people discovered / zero blossoms left to fall.”

“We’re the ones left to tell our stories. If we have any idea about our grandparents’ or our parents’ generation, it’s up to us.”

Hashimoto chillingly follows the poem of nuclear destruction with two poems, “A Barrack’s Window, Outside” and “A Barrack’s Window, Inside.” The barracks are at Minidoka, Idaho, which during the war housed part of the one hundred twenty thousand incarcerated ethnic Japanese immigrants and citizens. The poems detail the ruined, bleak landscape seen outside the camp housing: “Nothing was nice / or clean. Nightfall— / black-haired babies / bawled all the time. / Wind wiped away. / Now who is who?” In “August 9th,” the nuclear bomb accomplishes a fast obliteration of families; incarceration in the camps brings a slower obliteration of families.

Part III “No Wrong Turnings,” focuses on the post-WWII years when families are back home. Mothers piece together family life, and buddies grieve for their friends lost in WWII Europe. Fathers withstand ongoing prejudice and economic loss from their farms being ruined, homes burnt, and stores gutted. In spite of the tough times, these poems are gentle-hearted, dealing with aunts, a grandnephew, husband, and a professor. An adult daughter tends to her elderly father. The daughter adapts her pace to accommodate her father’s short steps on a stroll. In “Steelhead Fishing,” the question is posed: What is a good life for an elderly Japanese American man? Can it be the solo activity of steelhead fishing? Does anyone take his desires into account? “When was he asked, and who asked him: / What’s been the best day of your life?”

In Part IV “Those Left to Tell,” poems display the values within the ethnic Japanese family that are held precious and what needs to be told. “Hard Shell Clamming” develops the image of strength in unity. “No barbs or bickering between us, we bumped shoulders together / becoming a buttress of siblings…” In “Badminton,” playing the game shows the family as young, vital, enjoying each other, and enduring. “We don’t know / how happy we are. In the fading // red afterglow, our family keeps playing.”

In an interview, Hashimoto recalls her father commenting on mixed-race fourth generation Japanese Americans. He reveals a sorrow, saying, “So sad.” Hashimoto asks him why, and he says, “All that Japanese now only tiny bit left.” An image in an earlier poem, “Submerged Clothesline, Salton Sea, 1983,” punctuates this sorrow: “My hands are full of clouds I pin to the line. / Each sheet turns and thins out of existence.”

Hashimoto speaks of who is left to tell. “The younger kids aren’t picking it up and passing it down…. [T]he next generation that is aging…is my generation. We’re the ones left to tell our stories. If we have any idea about our grandparents’ or our parents’ generation, it’s up to us.” This is the obligation that infuses her poems.

Recommended

A Review of When We Were Gun: A Narrative Poetry Cycle by Deborah Schupack

A Review of Apostasies by Holli Carrell