The Sailor, the Witch, and the Faggot From Issue 293.2

Secret Women

Anchors on chiefs’ and officers’ hats blaze

bronze, gold. Fear holds us, though technically

seamen are navy property. But sex?

Dismissed. Inspection done. Red stripes. White crow.

Each left sleeve flies one. Our navy blue wave

falls apart. First night in Honolulu.

Girls love us. Gays too. I’m nineteen. My white

hat gleams like a seagull under streetlights.

I kiss another sailor. Don’t bother

justifying it. Part of its mystique.

Khaki conspiracy of fear. A lip

lock in a bar. It’s payday. Tabasco

moon, where witches send secrets. Wisconsin:

no one recognizes me when I’m home

on leave. Rednecks tell faggot jokes. I smile.

“Purple Kool-Aid sea” I say. They nod. Drink.

Quietly I work. No UCMJ

ready to jail or discharge me. Nights I

summon secrets from the moon. Bits of ash.

Tiny rain of flakes from mirrors. Once beg-

un, each secret summons another. Self

viewed in pieces. A broken vase. All me:

Witch. Sailor. Queer. My poems, mostly unread

except by a few poets. Mosaic.

Y and X chromosomes balanced. Blowjob.

Zipper. Moon always broken on the sea.

--North American Review 293.2 Fall 2008

Secret Women received an Honorable Mention in North American Review’s 2008 Hearst Competition. The poem’s a Double Abecedarium—the first and last letters of each ten-syllable line adhering to an alphabetic pattern. Fudging is allowed, especially at the end of lines. For a more expanded definition of the form, and its composition, see my Aug. 6th, 2015 blog on this same site.

Instead of a technical article on the poem’s structure / form / composition, I’d like to write about the personal experiences and social history behind it.

I was about 45 when I wrote it, spending 10 – 20 hours on its composition. This poem is a mosaic. The symbols do a lot of speaking for me in this piece. I let things get a little surreal. Various aspects of self (occultism interests / nature / sexuality / navy time), merged on paper for the first time, in a form of self-healing / psychological unification.

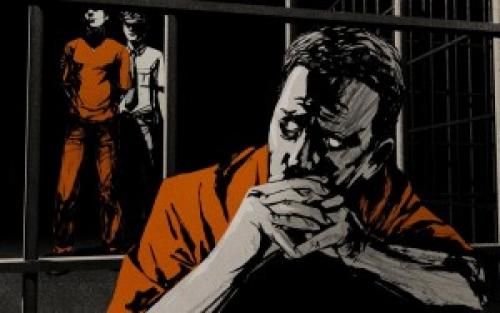

I served in the Navy from 1980 to 1990, before the military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy, and its present-day tolerance of openly gay members. Homosexuality / bi-sexuality resulted in immediate discharge from active duty, under the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), the set of rules by which all  servicemen and women are subject to various penalties for forms of misconduct. If you were caught,you were simply gone—even if you were 19 years towards that 20-year pension the service was famous for. Not a penny of severance pay. So of course everyone was in the closet. There was an atmosphere of fear in general. That was the worst thing about the military. The constant paranoia eroding your mind. In a way, it was like being in jail. Your life was in the navy’s hands. You were officially government property, and could even be written up and punished for destruction of government property if you got a really bad sunburn. This almost happened to me as a 23-year-old reporting to a small communications station in the Australian Outback. I flew in during the weekend, and hit the beach for some sun, not knowing how strong the sun actually was “down under.” Lobster-red come Monday, my new boss was less than pleased. But since I hadn’t yet had my base indoctrination, I was off the hook.

servicemen and women are subject to various penalties for forms of misconduct. If you were caught,you were simply gone—even if you were 19 years towards that 20-year pension the service was famous for. Not a penny of severance pay. So of course everyone was in the closet. There was an atmosphere of fear in general. That was the worst thing about the military. The constant paranoia eroding your mind. In a way, it was like being in jail. Your life was in the navy’s hands. You were officially government property, and could even be written up and punished for destruction of government property if you got a really bad sunburn. This almost happened to me as a 23-year-old reporting to a small communications station in the Australian Outback. I flew in during the weekend, and hit the beach for some sun, not knowing how strong the sun actually was “down under.” Lobster-red come Monday, my new boss was less than pleased. But since I hadn’t yet had my base indoctrination, I was off the hook.

It took about a decade after I left the navy before I was able to start writing about my experiences. For years it was a part of my life I repressed. Easy to do in central Wisconsin, where the only navy presence was the town recruiter. Most veterans were invisible in the 1990s. People didn’t routinely thank you for your service like they do now. When I came back to Wisconsin in 1991, if I happened to mention I was a vet, people thought I was a horse doctor.

The military is a caste system. Off-duty, you only associate with others within a couple pay grades (ranks) of yourself. Otherwise, the fraternization can erode good order and discipline (the fear of authority that prompts fast reaction to an order in an emergency).

Also, unit integrity is compromised. You have to have each other’s backs in combat, a shipboard fire, etc. Hard to do if most of the guys in a unit are homophobes and a few are gay.

I remember being secretly tested for HIV in 1985, by a sympathetic and discreet medical officer. He’d tested someone a few months prior, word somehow got out, and that person was quickly discharged.

Military personnel go on leave (vacation) for anywhere from 30 to 60 days when transferring between duty stations (generally every 2 – 3 years). There’s an inherent sense of dissociation when you come back home with a pile of cash to have a good time. You get to decompress, become a little more yourself. Experience freedom and solitude. The military is a 24 / 7 thing. You

every 2 – 3 years). There’s an inherent sense of dissociation when you come back home with a pile of cash to have a good time. You get to decompress, become a little more yourself. Experience freedom and solitude. The military is a 24 / 7 thing. You

generally live on base, in a barracks with your co-workers (dorm-like, with a couple roommates). I didn’t have my own private

room until age 23, when I’d already been in 5 years, and had earned some rank.

Besides being a closet bisexual in the navy, I was also a closet Wiccan (a form of nature religion whose adherents practice ritual magic). I was stationed on a small ammunition ship ported in Oakland (1983-4). Shipboard life means total loss of privacy. I remember renting a motel room for a weekend one payday in my early twenties so I could perform a self-dedication ceremony to Cernunnos and Cerridwen (Celtic horned nature God & Goddess). Studying the occult was much harder in the pre-internet age. Plus, I was a solo practitioner, completing a workbook type course via the mail, found in the back of Fate magazine (which still exists). This was the first of many steps over the years in which occultism played a role in my evolution. While Secret Women mainly focuses on my sexuality at that time, it has a sister piece, Navy Witch, that focuses on my concurrent spiritual quest. It’s kind of a flip side version.

Navy Witch

A ship’s a hole steel punches in the sea.

But our ship? Future crater. Floating bomb

carrying fuel, named for a volcanic,

dormant Maui peak. We sat at pier side

each night, Supply Center Oakland. The base

famous for its CO—the father of

god-of-rock Jim Morrison, “Lizard King.”

Haze-gray paint on everything. Our berth-

ing compartment held sixty guys. Young, bi

journalist, I’d stay at the Flying J

“kleen rooms” motel one night each payday week,

leave USS Haleakala. All

my shipmates but one thought a blonde, her name

Nora, waited at my cab ride’s end, on

one of those vibrating beds you have to

plug quarters in. The truth? An envelope.

Q & A worksheets. Spells by mail. Antique

ritual knife cutting symbols in air.

Self-trinity of sailor, witch, queer—years

torpedoed, sunk, before I could admit

you three to me, myself, I. We’re tabu.

Volanticas, Roman witches, some of

which were fed to volcanoes. I see how

exposure’s constant threat warped. No phoenix,

yester-me survived and left the navy.

Absolved with time my life absorbs its selves.

Previously published in Verse Wisconsin #103 Summer 2010 online edition

Illustrations:

Wanting to Kill by Clay Rodery. He is a painter and illustrator who lives and works in New York City.

A Surveillance State by Anthony Tremmaglia. An Ottawa-based illustrator, artist, and educator. His clients include WIRED, Scientific American, Smart Money, HOW, and San Francisco Weekly.

"Untitled" by Eric Piatkowski. Raised in Arizona, and after a few years of working in theater, Eric Piatkowski switched gears and studied illustration at the Pratt Institute. Now in Des Moines, he splits his time between drawing, drawing, and more drawing. Give him a call, he just might be the perfect man for the job. Prints of artwork featured here and elsewhere are available through Etsy at Eric Piatkowski Art.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop