A Review of Lessons with Scissors by Jeanne Marie Beaumont

Gaston Bachelard states about the space of houses, a motif that runs throughout Jeanne Marie Beaumont’s new book of poems, Lessons with Scissors: “If I were asked to name the chief benefit of the house, I should say: the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” Throughout the sections of her book, Beaumont masterfully uses the metaphor of the house cut out of space, like a poem within a poem, to gain entry into the past and future. In “Catastrophe Waltz,” about a house that had flooded, she writes, “I can’t be found in old familiar places. / I’m in exile. I crawl out of a window. / I may wake tomorrow.” And yet later, when the reconstruction of the house as the past is lost to memory, she writes with wry humor, “Now I am removing the doorknob to the past. // Where I go is nowhere. I stay put.”

There are so many ways to interpret that “I” which is part of Beaumont’s bewitching magic because the art of metaphor is not any longer a one-to-one proposition, but decentered and multifaceted. That “I” could reference the speaker as poet, but it could also be the poem speaking self-reflectively about its own content. A poem, like a house, is a space to enter, to live and die in, albeit within the constraints of the poet’s imagination. For all the music she employs in her lines, the attention to harmony, the visual detail, Beaumont’s demeanor in the poems is essentially cool, calculated, at times funny, and occasionally intellectual, but always engaging the reader through her own curiosity. She is a poet who asks questions, who puzzles through enigmas of past and present, and she seems to me a master at building an uncommon sense of trust within the reader, who is enticed to step into the dramatic momentum of the poem, rather than remaining a spectator. The house is inviting, yes—it lets us in, but once inside it, like the poem itself, it envelops us in its own story.

Beaumont’s artistry makes each poem a stage upon which the speaker acts, and perhaps more strikingly, it culminates in a dramatic voice that delivers the poet’s words. She is one of the most versatile poets when it comes to presenting the many guises of poetry in a postmodern world. She trusts words, but she also “un-trusts” them and delivers on rhymes, puns, etymologies with a plain speech that is exquisitely shaped and saturated with color.

Indeed, in an age in which meaning itself has become dubious, given the epistemic shift initiated by modernism, and as a result of the split between signifier and signified that denies art any unifying function, it has become far more difficult, and even unfashionable, for poets to articulate a potential interconnection between personal vision and a reader’s response to that vision. But this is what Beaumont masters with such fluidity: syncretisms and cultural cross-fertilizations of traditional and innovative texts. She brings an elegant artifice to her poem’s surface and disarms us with their light and dexterous magic.

A poem, like a house, is a space to enter, to live and die in, albeit within the constraints of the poet’s imagination.

She also incorporates in this book the ekphrastic, objects of inference embroidered with wit and dark humor as she, like so many poets begins the excavation of her past. In one of the opening poems, “Origin Story,” she characteristically begins with the impossible: “The problem of origin—how to begin?” And so she begins as poets do with the images that flood in, as she digs archeologically into the foundations of her past, which appears almost as a photograph, captured by the shutter. She characteristically guides (and guiding is one of the recurring tropes throughout the book perhaps due to her fondness for Dickens and the narrative voice) as she tries to make sense of her own genealogy, the fragments that seem to connect the way she brings attention to this place where we assume she has a history, recollected by objects such as “bent-pronged rakes” and “pruning shears.”

Beaumont is theatrical. She provides stage directions while speaking to the reader/reflexive self: “Now follow the clothesline attached just outside” and the mother who ritualistically has been pinning up the sheets drying all afternoon. The crucial line that could synopsize the entire volume with the woman, her mother: “working / slowly as though she does not want this to end.” That is the sum of how narrative works, the deferring of the ending, and it is also how poetry, perhaps more blindly, feels its way toward a conclusion that resists its own conclusion, like any living thing; thus, the end of the origin story is “working so slowly [like her mother pinning up sheet after sheet, [word after word] as though I don’t want this to end.” That is the paradox: there is no end to the origins, only more digging.

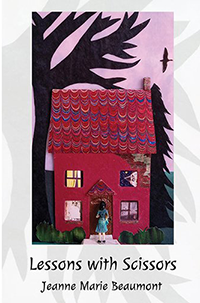

Such digging inevitably brings us back to childhood. As Bachelard states: “Like a forgotten flame, a childhood can flare up again within us.” Beaumont herself designed the book cover for Lessons with Scissors, a childlike drawing, or pastiche of a house that seems to illustrate at least one of the houses encountered in the book. The figure of a girl wearing a wide-brimmed hat at the archway of a decorative house as if about to knock or enter. There are four windows, and each captures a section of the book—from a young child clad in a white dress; a missing pane, half of a painted doll’s face; and a window filled with lamplight. While poems about houses recur throughout the collection, they are by no means the only subject of the poems. Instead many of the poems partake from related themes and subjects, from language itself, to homage to poets, to elegies, and beyond.

Bachelard adumbrates the notion that, “every corner in a house, every angle in a room, every inch of secluded space in which we like to hide, or withdraw into ourselves.” Hence, even as the poet ventures into other realms of experience, the house returns as that space. Each poem is crafted like a house and built from a structure. A house is made out of an alphabet, and Beaumont, with formal virtuosity makes her message seemingly effortless and improvisatory.

The prologue is a dramatic monologue, “You Really Ought To” in the voice of a realtor trying to sell this house to the poet, or at least to entice by asking her to “Give this place a chance.” The dramatic monologue takes a logical position as a vernacular form because it posits no fixed center of “the self” and offers instead a surplus of alter selves, carved out of the tactility of language, something again that is part of Beaumont’s unique style. In the opening stand-alone poem, the realtor is selling the poet on its being synonymous with the poet’s own life and comfort, and her life is the poem: “I promise you that whenever the phone rings, it is someone who loves you.” This is a place of refuge, and as Bachelard suggests, “late in life we say we are going to do what we have not yet done, build our own house, a dream of ownership.” But ownership is just that—a dream. In the end, there is only dispossession, disarticulation, dissembling of what has been built. Fittingly Beaumont’s house by the third section transforms into the body, another place that houses the imagination, as well as the soul.

In section one, the framing and foundation of the house extend to other related poems about foundations such as “Self as Forebears” where personal history intersects with other personages and their histories, as she writes, going back in time, envisioning ancestral roots: “carders, weavers, dryers, finishers, and the fixers of looms— / bless that fixer—and the multitudes I lose in the // gloaming ... How dim it grows now in those uppermost stories” (stories being the pun for what does not end, and perpetuates itself by not ending). In a fine ekphrastic poem, one of my favorites, the speaker takes the voice of a diminutive figure in a museum painting, one that is barely noticeable, and speaks to the observer who may be appreciating more obvious aspects of the painting, and its verisimilitude: but she is housed in the painting, and can’t come alive, hence the title, “Strictly Speaking, I’m Already Dead”:

I could be anybody alive would happen, on a certain day,

to be lugging a small jug and bread to a sack toward

a shadowed dwelling, fated to be torn down, afoot

so long on the pavement, which is actually pigment,

that centuries later, strictly speaking, I’ve yet to arrive.

The speaker is fixed in time, as if caught in a photograph, and yet everything in the context of the painting is moving, living, and yet if we take seriously that this is a painting from life, that figure is “strictly speaking, already dead” even as she appears alive with each visitor admiring the painting. Beaumont’s mastery of the line, syllabically and rhythmically, her virtuoso versification even in free verse is always on display.

Other poems take leaps, surprising the reader, such as the poem “Since” since everything that happens occurs “since”—another nod to the ontological impossibility of finding the end to the beginning, “since”: “I can’t keep my eyes open since / all that’s happened since / nothing here I want to see.” Two elegiac poems end the section, with “Nursing,” a poignant poem about her mother’s nursing home, where her mother, along with the other residents had regressed to trying to play with dolls again: “Clothes would be lost / then reappear / swapped about / mismatched.” In the second stanza, she brings her own doll, “refound” Penny, to show her mother, “where she joined the nursery / of the nameless, unrecognized by her now / as was I, as was any.”

In the final poem of the section, the house becomes the grave, and as I’ve written in The Poetry of Loss: Romantic and Contemporary Elegies, contemporary elegies like Beaumont’s break with the conventions of traditional elegiac structure and expression, ceding to the endlessness of grief. In “Afterlife with Father,” she begins by recalling her father observing her writing poetry. Out of practicality, the father asks: “Why don’t you write a novel?” The daughter revives the father and dissociates from the initial memory of “sitting on the floor,” a memory that serves to screen more traumatic memory of her recognition of his death. The memory then prompts her to concede she wasn’t “really good at writing plots,” and the word “plots” causes her to associate with another memory—this time of a graveyard and its plots (like house plots). In the poem, he appears out of the grave, “nudging time’s door / between us,” full of longing for his life. It is the daughter who can grant him the “home” of the elegy, by allowing her to internalize the representation of the father and to respond to his death wish: “Now he tells me, I want to go home. Give me / my body back. Put me in a poem.” Poem, house, and grave all mesh together. The ending is bittersweet, sardonic, and moving.

Section two opens with “Homegone,” but this time it is the home that is under erasure, with the house having been “opened and closed like a shell.” It has shrunk in the distance of memory and is too far away, too distant even to be touched in memory. The speaker’s attempt at reconstruction can only happen vis-à-vis the imagination, otherwise lost to time. There are other poems that revisit childhood and the poet’s Catholic schooling. “Our Trespasses” vividly records her early experience of the schoolroom, where emphasis is placed on rows that imitate the lines of the poem, wherein the early indoctrination of the nuns leads the child to believe that the world is tainted by transgressions, even those that are purely accidental and carry no malice.

Discipline becomes the catalyst for rebellion, and also the breaking of rules meant for contrition, and so much of Beaumont’s works reflect this very early traumatic confrontation with sin, and confession. Beaumont is unafraid of experimentation with narrative structure, eagerly developing multiple perspectives and defying traditional conventions. Hence, she breaks down the conventional index by inventing one in “A Brief Index of the Life and History of Emily Jane Bronte,” where she reappropriates Bronte’s life into her own, inventing the aspects that seem most crucial matched to pages that do not exist in any biography. Her own version of the biography is both whimsical but also existentially aware that these events are her life, and can’t be ordered. The index comes at the end of the book, as a kind of linear epitaph, and refers back in time to what is most fleeting, and already fled.

Discipline becomes the catalyst for rebellion, and also the breaking of rules meant for contrition, and so much of Beaumont’s works reflect this very early traumatic confrontation with sin, and confession.

Throughout this section the voice remains always convincing, even as the monologuist changes from poem to poem. The voice throughout is chameleon-like, a voice that one might analogize as a conductor, or a tour guide, or master of ceremonies. The self is also decentered (who else could title a poem “Self as Suburban Rain”? ), improvisational, and freed of any unanimity, so that the reader is always surprised. And yet, there is a somber tone to some of the poems, such as when manifested in grief over her father’s death. The poet in the present alters the past by recasting memory in an entirely different light. What we readers feel is distinct tension between an interior and exterior selfhood, a sense of nebulous anxiety about existence itself: Will the next moment follow as it has been scripted, or will the child’s powerful and magical thinking alter her world, even when the child is an adult?

In the final two sections of the book, the themes of home, art, language, vision and memory are revisited in innovative ways. The complex of reality and imagination is never definitively resolved. The house itself, as Bachelard writes, “does not lose its objectivity.” There are houses in which we recapture the intimacy of our daydreams. “Lessons with Scissors,” the title poem of the book, has a tinge of the surreal in that the speaker is describing, metaphorically, the fusion of the image and the word, as a construction, or collage, made from objects/pictures, she has cutout from a contextual background and reconfigured in a new one. She regularly entertains the reader with visual puns: “He cuts a fine figure accrued new resonance.”

The poem ends with a nod to the surreal, perhaps comparable to a Chagall painting, in which each cut out item assumes a new identity, freed, in a way that we, as social beings will never be freed. But as the artist, as the creator of the fantasy world, she can find ways to compensate for that melancholy: “Once I gave a seahorse new clothes. / New clothes! A sharp nautical dress / and a French sailor’s cap.” The artist is free to create her world, something that has been sadly lost among a literary cadre of serious poets who have attached themselves to discourses that have abandoned fantasy and invention for fact and erudition. I do not mean to suggest that Beaumont is not erudite; rather, her keen intellect, always palpable, extends to her love of the fairy tale, the embroidered imagination, the daydream that Bachelard refers to as the geometry of the daydream.

The last section of the book deals with the somber inevitability of death, including elegies, and with the spectral ghosts that the speaker finds vestiges of. In “The Window,” a moving elegy, the speaker remembers a lost friend through the half-dream of the ancient fairytale:

From a snow-packed ledge I watched

thumbtack stars define night’s sky as a white wolf

to my right crept our cherished girlhood book.

Were you and wolf now one? Hungry again

And so soon? I woke alone. Lost friend ...

Again one marvels at the crafted language, the sonorous music of each line, the convivial engagement with the dead, more frank than most overwritten elegies that draw more attention to the poet than the beloved object now lost to the interiorization of their memory. Instead, there must be a continuing bond with the dead, rather than any finality to grief. The window stays open, and the friend appears to have already communicated with her through the poet’s memory of the lines of one of her poems: “I would have shivered, too, as stepping into the draft / from a window that never closes.” “Draft” has a double meaning; the draft suggests something unfinished—in this sense, her friend’s life will remain unfinished as she is mourned.

Lessons with Scissors is unlike any poetry book that one encounters—there is beauty in the dark entity of the house, and this takes on forces all on its own. What we as readers feel is an ability to rethink the narratives by which one lives, and to boldly shuffle and reshuffle the deck, creating a world made out of images that no one else can know until they are written down. But Beaumont takes that a step further, these images are written down in poetry, but they are also liberated to enter into each and every one of our soul-like houses. These houses, which we construct out of air..., the bodies we live in, the doors that let the guest in, and the light of moon or sun from which we can see from every page of the book, like every window.

Recommended

A Review of Portable City by Karen Kovacik

A Review of Haircuts for the Dead by William Walsh

A Review of Birdbrains: A Lyrical Guide to the Washington State Birds