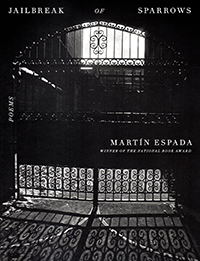

An Open Window: Jailbreak of Sparrows Throws Back History’s Shutters to Expose Light, Anger, and Heat in the Face of Oppression

In Jailbreak of Sparrows (Knopf 2025), Martín Espada once again proves to be a poet of witness, defiance, and astonishing tenderness. This collection moves between elegy, political memory, and moments of sly humor, reminding us that poetry can fling open the locked windows of history and let the birds out. Much like poets within the Puerto Rican diaspora, sparrows are the unassuming yet resilient survivors of oppression who sing their hard-won freedom, no matter what.

The title poem sets the tone: Espada tells the story of a poet imprisoned for his words, whose verses escape the cell and take flight. “The verses that flew like a jailbreak of sparrows from the poet’s hands,” he writes, conjuring both the fragility and the unstoppable force of language when it refuses to be caged. This image of sparrows slipping past the bars is the book’s beating heart: small, ordinary, or complex lives that become monumental in their struggle for freedom.

Throughout the collection, Espada returns to his Puerto Rican roots and the legacy of protest that shaped his family. In one piece, he recalls how his father, Frank Espada, captured the resilience of the Puerto Rican diaspora through his photographs: “‘Look at this’ was all he said, and all he had to say.”

In these lines, a father’s quiet directive becomes a lifelong command—to look, record, and remember. And in so doing, the poet becomes equal parts witness and mystic; one who transcribes material that, much like his father’s photographs, captures meaning that can’t be translated into ordinary language.

Espada’s gift has always been to braid the intimate and the historic. He writes of his boyhood and neighborhood fights sparked by the pride of seeing Roberto Clemente on TV—a reminder that even childhood skirmishes carry the weight of representation and belonging—the collection surprises in its penultimate section, where Espada shifts from political witness to playful invention.

He voices odd, overlooked creatures: a bat with vertigo, a polar bear mascot, even Frankenstein’s monster. In “Love Song of Frankenstein’s Insomniac Monster,” he writes, “You are gone. I clomp down the stairs… You reach for me, oh bolted, screwed, sewn-up, fiendish me.” This moment, among others, is Espada at his most tenderly absurd, finding beauty and love in what the world might dismiss as monstrous, just as those who love us should do unto us.

If there’s a signature to Espada’s work, it’s that he never lets language close the blinds on history. Each poem here is an open window, a jailbreak in miniature.

In addition to being a booming voice that echoes in the face of oppression, whose barbaric yawp resounded long before social justice became fashionable, Espada has another lesser-known attribute that merits attention: His work is not only fierce, it’s laugh-out-loud funny, especially in the entire previously mentioned third section, aptly entitled, “Love Song of the Disembodied Head in a Jar.”

This balance of humor and frustration emanates throughout poems like “Love Song of the Polar Bear Mascot at McCoy Stadium in Pawtucket, Rhode Island,” which begins, “My head is stuck! I am stuck inside my head like a lunatic or a poet!”

One doesn’t need to be a writer to appreciate the self-deprecating playfulness. But Espada’s genius treads a subtle line between humor and his signature fire, as the mascot persona describes, much like a poet, the heavier aspects of performativity:

At the end of the game, my head is still stuck in my head. My zipper dangles,

derailed in the seventh inning, a little train skidding off the track on my belly.

I fold the chairs and tables in the ticket office, still stuffed in my polar bear

mascot costume, drenched as if I pumped my arms and legs to score

the winning run in the last of the ninth, the reverie of mascots everywhere.

Here we can see Espada not only speaking to the loneliness of the poetic craft but also the way poets are forced to perform while often feeling, much like a mascot or a soon-to-be extinct species, as someone working within an underappreciated genre does: trapped, suffocated, and overheated, even in moments of the crowd’s adulation, as the speaker admits, “But they love me. They love me when I fire my plush baseballs / into the crowd… the toddlers love me when they shriek in my face, thinking I’m real.”

The book, dedicated to his wife, the poet Lauren Marie Espada (Schmidt), draws heavily on his beloved, especially in her teaching profession. The speaker makes it clear that teachers are activists and heroes, as evidenced by poems like “Isabella’s Red Dress Flutters Away,” in which the teacher subject, despite warnings from her colleagues, refuses to give up on a troubled young woman, driving her to the ER when she suffers at the hands of a boyfriend’s abuse.

But the book never drifts too far from its sense of moral outrage and its role as a voice for the voiceless. Again and again, Espada brings us back to those the world tries to forget: the teacher who refuses to give up on her beloved students, the laborer scrubbing floors, the tenant facing eviction.

Another poem of remarkable tenderness is “The Love Song of the Atheist Marionette,” where the Pinocchio–like speaker announces, “I say God is not my puppet master. God does not make me jump at nothing,” but then in the next breath, realizes that illness, not God, has cut the puppet’s ties with gravity, and before meeting his impending fate, admits, “…you caught me before I hit the floor. You called puppet 911.”

Even when he writes about reptiles—iguanas in a graveyard—he insists that we see how life persists: “The dead eyes of the iguanas, keeping vigil… will never / see the asteroid of their extinction…”

Here we see the iguanas in a post-apocalyptic landscape, one where the reader is reminded of the resilience of Puerto Rican people in the face of colonialism, which primarily engages the current political climate as well, as we frenetically tread to remain above water while the tides of fascism rise an inch more every day.

If there’s a signature to Espada’s work, it’s that he never lets language close the blinds on history. Each poem here is an open window, a jailbreak in miniature. Whether he’s memorializing his father, resurrecting radicals from Puerto Rican history, or putting a monster’s heart on display, Espada’s poems demand that we keep watching, listening, refusing to forget.

Jailbreak of Sparrows reminds us that freedom rarely comes in thunderclaps. Sometimes, it comes in wings brushing past or beating against a window left ajar—or in a line of verse that slips the bars and makes it out into the world.

Order Jailbreak of Sparrows today

Recommended

A Review of Portable City by Karen Kovacik

A Review of Haircuts for the Dead by William Walsh

A Review of Birdbrains: A Lyrical Guide to the Washington State Birds