A Picture of Stack Lee

I suspect that one of the reasons “Stack Lee” Shelton, a small-time St. Louis hustler, became Stagolee, the archetypal “badman” of Black story and song, is that he spent his life auditioning for the part. He liked to rob people, gamble, get high, and generally do as he pleased, and when he met resistance he tended to hit it over the head with the butt of a Smith & Wesson.

But in February of 1896, Stack Lee did something worthy of an even more storied figure from Black folklore, the trickster: While awaiting trial, he duped the sheriff into letting him out of jail for the day. He said that he needed to go see his dying mother (who had actually been dead for twelve years), and two hapless deputies ended up chaperoning him around the city. Stack laughed it up on the street with old friends, enjoyed an intimate reunion with his girlfriend, and hit the saloons, buying everyone a round of drinks at the very bar in which he’d killed Billy Lyons less than two months before. The deputies didn’t return him to the jailhouse—so drunk he had to be carried—until early the next morning.

That’s the story as it was told in the St. Louis newspapers of 1896, anyway. I have no idea how much of it is true. I know that some of it is outrageously false. Shelton’s mother, for example, had not been dead for twelve years in 1896—in fact she would die the following year. And although the scandal was exhaustively covered for several days by both the Post-Dispatch and the Republic, that coverage is so gossipy, self-contradictory, racist, and full of motivated editorializing that every word of it is suspect. But its failure as journalism is precisely what makes it a significant cache of artifacts for the Stagologist to study. One of the oldest and most widely circulated sets of “Stagolee” song lyrics, first collected by John Lomax in 1910, includes these verses:

Gentlemen of this jury,

You must let poor Stagalee go;

His poor and aged mammy

Is lyin’ very low….

Gentlemen of this jury,

Wipe away your tears,

For Stagalee’s aged mammy

Has been dead these ’leven years.

There can’t be much doubt that Stack Lee’s day out, and the breathless accounts of it that appeared in the local broadsheets, helped to shape his emerging legend.

How might Stack Lee’s coloring have affected his daily dealings with the world?

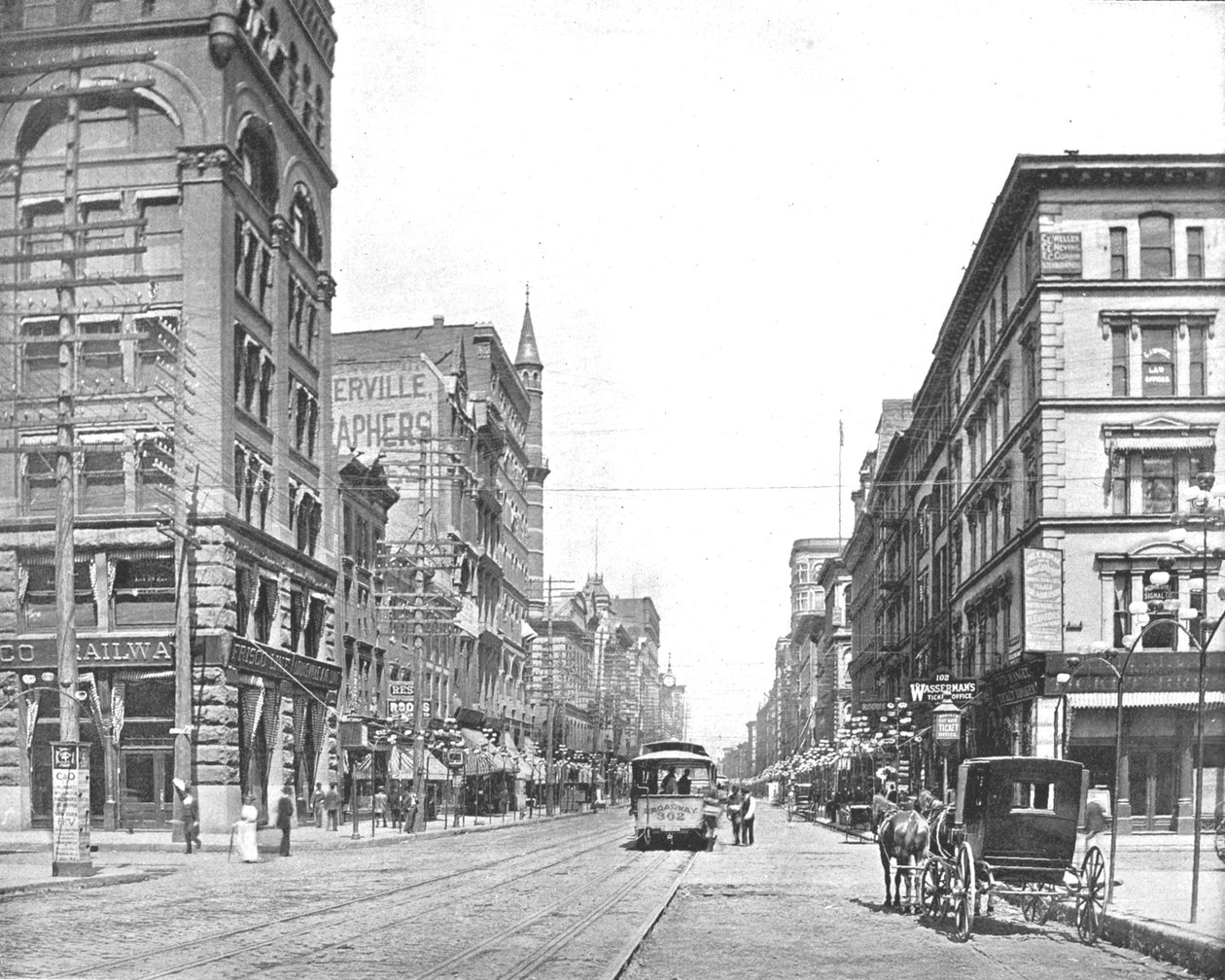

One of the follow-up stories in the Republic preserved an even more remarkable artifact—an artist’s sketch of Stack Lee, which as far as I know is the only surviving image of him. Photographs didn’t regularly appear in the St. Louis papers until a few years after Shelton’s incarceration, and no other drawings have surfaced. Most of the Rogues’ Gallery—the archive of nineteenth-century mug shots taken by the St. Louis Police Department—was likely discarded sometime in the 1950s. And the state penitentiary hadn’t begun photographing inmates when Shelton arrived there in 1897. When I discovered the sketch in an online newspaper archive in 2021, I felt like the archaeologist who had gazed upon the face of Agamemnon. It is republished here for the first time in 130 years.

Newspaper artists at the time, including the Republic’s, typically used shading to denote darker skin, so his fair complexion is probably a fair representation. This isn’t surprising—or shouldn’t be. Shelton was described as “mulatto” in his penitentiary record, multiple newspaper articles, and the 1880 census. In the early 1980s, the researcher John Russell David spoke with a 102-year-old woman who had seen Shelton, and who remembered him as “almost white.” Near the end of his life, in 1912, a Detroit newspaper called him “a white man, known by the police from one end of the country to the other”; Shelton had been a fugitive the previous year, and that misdescription may have been based on a now-lost mug shot. And although the “one-drop rule” wasn’t codified into law until the twentieth century, Blackness and whiteness have always had more to do with parentage than appearance.

But even knowing all of this, I was still surprised by the picture. This was the man who would become, with minimal modification of his story, the “baddest n---- who ever lived.” Blackness is absolutely central to Stagolee’s folkloric identity, a fact reflected in every artist’s depiction of him; you will search the internet in vain for a light-skinned Stagolee. As Greil Marcus writes, “[P]roof that the original Stagolee was white would constitute almost as deep a smearing of cultural identity as Freud’s claim that Moses was an Egyptian.” And yet here he was, looking, in the words of a friend of mine, “like Walt Disney on a bad day.”

The sketch made me wonder how the subtleties of Shelton’s appearance influenced his life. Racism, like soot, stained everything in Gilded Age St. Louis, but what about colorism—inter- and intraracial discrimination based on skin tone? Another early version of the Stagolee ballad, written by a St. Louisan, remembers him as “high yellow,” implying a degree of social privilege. How might Stack Lee’s coloring have affected his daily dealings with the world?

I shared the image with several scholars and writers, and their provisional consensus was that it probably didn’t, very much. Prior to the Civil War, light skin had been all but required for admission to St. Louis’s “colored aristocracy,” but Emancipation and Jim Crow scrambled the old categories. “Colorism was not happening in the way that it happens today,” said author and Georgetown University professor Zandria F. Robinson, “or in the way that we’re imagining it, because of the hardness of the rule of hypodescent, the hardness of the color line. That one drop made you absolutely Black; it didn’t matter what color you were.”

At the same time, according to the novelist and essayist Darryl Pinckney, new forces were facilitating social ascent within the Black community. “The importance of education to the future of the race changed the value of light skin color in black America,” he told me in an email. “Light skin and being related to old master weren’t the key definitions of the black aristocracy anymore. Achievement was.”

Dangerousness, full pockets, and prowess at the craps table were what commanded respect.

Light skin may have been especially inconsequential to Stack Lee, a member of what Pinckney called “the anti-social black classes, the sporting life people, who in many cases said they preferred to be outlaws rather than bend their knees all day for white people.” The saloons, hop joints, gambling dens, and brothels where Stack Lee spent his days and nights were racially integrated to a degree unimaginable outside of the vice district. Dangerousness, full pockets, and prowess at the craps table were what commanded respect. “The sporting life, vice, imitated Bohemia in the social mixing that took place there,” Pinckney wrote. “The whites Stagolee must have known in that world were as criminal as he. He had no need for the social mobility of light skin. There wasn’t any to be had in it.”

That may be complicated somewhat by Stack Lee’s tendency to turn up in “colored society.” He attended balls and cakewalks, had upwardly mobile and civically active friends, and was an officer, at least briefly, in a social and political organization called the “Colored 400,” which styled itself as the Black smart set. But I’ve studied that crowd about as closely as historical documents will permit and found minimal evidence of colorism within its ranks. These two sides of Stack Lee may seem tough to reconcile: the erratic, violent criminal and the polished young man-about-town. But in fact there was considerable overlap between the fashionable Black elite and the vice-district dwellers; in 1890s St. Louis, making money through vice was one of the few ways Black people could afford to be fashionable.

There was a time when scholars probably would have seen Stack Lee’s light skin as his origin story—the source of his anti-social behavior and, by extension, his legend. “The person of mixed blood, it is generally believed, is more likely than the black to attempt the part of the ‘bad’ Negro,” H.C. Brearley wrote in 1939.

This is probably true, for the average mulatto feels superior to the blacks and often welcomes a chance to demonstrate his importance. Besides, he resents even more than does the black the racial discriminations practiced by the whites. His “almost but not quite” status is a precarious one and needs to be bolstered by public approval. If he has luck and courage, he may, by playing successfully the role of the “bad” negro, be assured of the prestige he yearns for.

Such essentialist thinking, ironically, may subject Stack Lee to a colorism he never encountered in life. “America had a hard time imagining the social destiny of light skinned blacks,” Pinckney wrote, “so the tragic mulatto emerged as a type to say mixed people would never fit in after all. Mixed race women were tragic, mixed race men a threat in their resentment.”

Needless to say, all of this is speculative. Pinckney ended one insightful paragraph of his email with, “Maybe I’m wrong,” and that’s probably how I should end every paragraph. There’s only so much one can infer about the long-ago life of a man who left no journals or letters, just as there’s only so much one can learn about how he looked from a small black-and-white sketch. According to Robinson, the newly discovered image of Stack Lee is valuable less as a portrait of a man than as a mirror in which its viewers might see themselves more clearly. “What’s interesting,” she said, “is that, in our modern eyes, it’s hard to see this Stagolee figure as anything other than darker skinned. We can only imagine a bad man as a bad Black man.”

Recommended

The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

Crossing Paths

I Have Only Dreamed You Dead, For Now.