The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

How the Baddest Man in the St. Louis Underworld Failed to Become a Folk Hero

In the summer of 1942, in Coahoma County, Mississippi, the folklorist Alan Lomax recorded an elderly plantation worker named Will Starks singing songs he’d known most of his life. A number of them were murder ballads that had clearly come down the river from St. Louis, including “Frankie and Albert” (“Frankie and Johnny”), “Duncan and Brady,” and “Stackerlee.” The latter two Starks claimed to have learned from the same levee-camp worker in 1897, “the year of that high water here.”

Don’t care nothin’ ’bout your children.

Don’t care nothin’ ’bout your wife.

You done stole my Stetson hat

And I’m gonna take your life.

Oh, that bad Stackerlee.

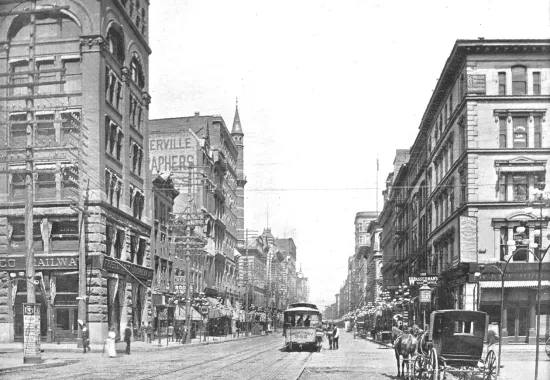

Every character Starks was singing about had been a real person, and, remarkably, part of the same small community—the St. Louis vice district of the 1890s, which must rival the Mississippi Delta of the 1930s for per-capita contributions to the American musical canon. St. Louis also boasted half a dozen thriving daily newspapers, most of which are now digitized, allowing researchers to study the events that inspired those songs and see how much of a folkloric makeover they got. The real Frankie Baker shot her abusive boyfriend once in her apartment and successfully pleaded self-defense; in the “Frankie and Johnny” song tradition she became the jilted avenger, hunting down her two-timing lover in a barroom and blasting away. Harrison Duncan went to the gallows denying that he’d shot Officer Brady in a saloon melee; in song he became an enraged bartender who’d had enough of the cops busting up his gambling operation (“Brady said, ‘Duncan, you’re under arrest.’ / Duncan shot a hole in Brady’s chest”). “Stack Lee” Shelton was a gambler who shot a man for stealing his hat; in the “Stagolee” songs he became … pretty much exactly that. He didn’t need much revision to be the “badman” people wanted to sing about. This is all consistent with a pattern that folklorists have long observed: Unlike white outlaw ballads, which tend to airbrush their historical subjects, turning murderous thieves like Jesse James and William Quantrill into righteous Robin Hood figures, Black “badman” ballads push their protagonists in the opposite direction—toward antisocial rashness and self-interest, qualities for which the songs make no apologies. (In a racist society, self-interest is its own sort of righteousness.)

Starks’s repertoire also included “Ollie Jackson”—another badman ballad that recounts, with astonishing specificity, the 1901 killing of two brothers over a craps-game dispute in St. Louis. It must have been composed immediately after the shootings by someone impressively familiar with the facts. Four decades later and four hundred miles to the south, Starks sang the correct names of the killer, both victims, two witnesses, and the owner of the saloon, as well as the intersection at which it stood, the day of the week, and the contested amount of money (seventy-five cents).

Dick Carr had the dice,

Bet six bits he’d pass.

Ollie Jackson faded him

And that was poor Dick’s last.

When you lose your money, learn to lose.

It’s hard to overstate how lucky we are that Lomax recorded this performance. Of all the songs that survive from the era of Black ballad-making (roughly 1890–1910), it’s the only one that describes a real event so thoroughly and accurately, meaning that it’s probably the closest thing we have to a Black folk ballad in its original form. And that form challenges some common assumptions about Black songwriting. According to D. K. Wilgus, the scholar who coined the term “blues ballad” to categorize such songs, their lyrics were often elliptical and digressive, unlike the straightforward narratives of European ballads. “The blues ballad does not so much narrate the events of a story as it celebrates them,” Wilgus wrote. The fact that “Ollie Jackson” is so reportorial suggests that what Wilgus called the “fragmentary nature” of blues ballads wasn’t their nature at all. When they were new, they were perhaps just as linear and minutely detailed as any English broadside ballad. They had simply been “sung to pieces” by the time they came to the attention of folklorists.

“Ollie Jackson” must have traveled in every direction. Starks told Lomax that he’d learned it from a Kansas City man. Other collectors have turned up variants in Indiana and Virginia. Bits and pieces of it migrated into Furry Lewis’s version of the Stagolee song and into more obscure Southern ballads like “Spotty and Dudie” and “Willie Warfield.” But over time, the song seems to have faded from the American folk-memory. Compared to Frankie, Duncan, and Stagolee, Ollie Jackson is a nonentity.

Hearing the song in its pristine form, and learning about the extraordinary life of its title character, I couldn’t help wondering why. Ollie Jackson was both the envy and the terror of St. Louis’s underworld in the first decade of the twentieth century: a gambling boss, nightclub owner, early baseball magnate, and according to some sources the richest Black man in the city. He had two automobiles at a time when most people had zero, live-in servants, “the most spectacular private collection of diamonds” in St. Louis, celebrity friends, and a song circulating about how dangerous he was. Ollie Jackson was larger than life in ways that Stack Lee would become only in his mythological afterlife, and seemingly the stronger candidate for Black folklore’s “badman” pantheon. But as his worldly fortunes waxed, his legend waned. It was Stagolee who would flourish in the folklore, even as his namesake languished in prison.

Recommended

A Picture of Stack Lee

Crossing Paths

I Have Only Dreamed You Dead, For Now.