The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

On Christmas night 1895, “Stack Lee” Shelton shot and killed Billy Lyons in Curtis’s saloon, allegedly for refusing to give him back his hat. Lyons may have taken a threatening step or two toward Shelton with his hand in his coat pocket, which may have contained a knife, but a jury found Shelton guilty of second-degree murder.

Over the next several decades, Stagolee—a.k.a. Stackerlee, Stack O’Lee, or Stagger Lee—became the quintessential badman of Black legend. He avenged the theft of his hat in section-gang songs, on blues records, on the Chitlin’ Circuit stage, and on Top 40 radio. Lloyd Price’s “Stagger Lee” was the number-one single in the country for four weeks in 1959 and today is a rock and roll classic. Stagolee is generally recognized as the father of the Blaxploitation “bad mutha—” and the grandfather of the ready-to-die gangsta rapper.

The degree to which the songs preserved the original story is remarkable, particularly given what an unremarkable story it was. At some point early on, gambling entered the narrative (“Stagolee threw seven; Billy swore that he threw eight”), and Stagolee’s badness has taken on outrageous and even supernatural dimensions over time. But the legend’s animating event has never really changed: Stack Lee shot Billy Lyons in Curtis’s saloon, and 130 years later, Stagolee is still shooting Billy Lyons in song.

This incipient folk-fame wasn’t of much use to Stack Lee Shelton; in fact it may have hurt him. In 1897, he began serving his twenty-five years in the state penitentiary—a severe sentence, in light of Stack’s plausible self-defense plea, that one local politician later attributed to “a strong prejudice existing against him at that time.”

Two years later, Bill Curtis moved his saloon out to 19th and Chestnut streets, and it was there that a young gambler named Ollie Jackson shot and killed both of the notorious Carr brothers, Dick and “Babe,” on June 9, 1901. This time it really was a dice-game dispute. There are no surviving transcripts from the coroner’s inquest or the criminal trial, but newspaper accounts and Will Starks’s lyrics substantially agree on what happened: after an argument over who was entitled to the seventy-five-cent stake, the Carr brothers came at Jackson.

Ollie Jackson won the bet.

Dick wouldn’t turn it loose.

Dick started for his pistol

And Ollie said, “It ain’t no use.

When you lose your money, learn to lose.”

Ollie Jackson shot Dick Carr,

He dropped down to his knees,

And Babe Carr throwed up his hands,

“Don’t kill my brother, please.”

When you lose your money, learn to lose.

Babe Carr, he jumped up,

Started round the table.

Ollie leveled that Colt of his,

Shot Babe below his navel.

When you lose your money, learn to lose.

Jackson probably shot Babe through the heart. That’s what three different newspapers reported, and they, unlike the lyricist, weren’t trying to find a rhyme for “table.” In other respects, though, the song helpfully corroborates the coverage. Deadly shootouts between dangerous men were common in that part of town, and witnesses, understandably, tended to exculpate the dangerous man who was still alive. The song’s anonymous composer was presumably freer to say what really happened, which makes his depiction of Dick Carr as the aggressor that much more credible.

Jackson must have perceived at least some risk of a long prison sentence, though, because he pleaded guilty to manslaughter in the fourth degree—a now-obsolete charge reserved for those who had acted in self-defense but had also provoked the fight that made it necessary—and was sentenced to two years. On December 14, 1901, he arrived at the state penitentiary in Jefferson City, where Stack Lee was already four years into his term. The two had almost certainly heard of each other by then, given the overlap in their social circles and the attention both of their crimes received. Their first encounter in A-Hall, the gloomy stone edifice where all of the prison’s Black inmates were housed, may have been a frosty one. Both Carr brothers had been friends of Stack Lee’s, and Babe had signed a petition calling for his parole. It’s also easy to see how Shelton, serving twenty-five years for killing a man in Curtis’s saloon, would have resented someone serving two years for killing two men in Curtis’s saloon.

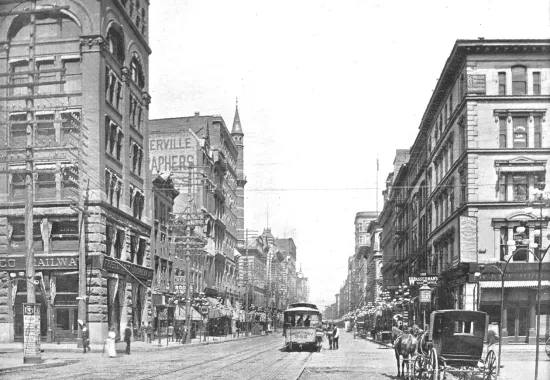

Jackson didn’t even stick around that long. On June 8, 1903, he was discharged under the “three-fourths law,” which provided early release for good behavior. Still in his twenties, he returned to St. Louis and went to work immediately building his vice-district empire. His progress was whiplash-inducing. In two years he opened the Modern Horseshoe Club at 23rd and Chestnut—a restaurant and social annex to the headquarters of a major Black fraternal organization, a chapter of the Elks. It was also a “lid-lifting club,” serving liquor on Sundays in defiance of the city’s “lid law,” and a front for illegal gambling. Jackson spared no expense in decorating: “The finest furnished club in St. Louis, making no exceptions, is the one conducted by Ollie Jackson at 2307 Chestnut,” wrote the Topeka Plaindealer, a prominent Black newspaper, in 1907. “The walls are hung with costly paper, and decorated with mirrors, the ceilings are frescoed, there are handsome chandeliers in bronze and gold and the finest imported Parisian carpets.” The leading Black newspaper of St. Louis, the Palladium, went further, declaring it “the finest club in the United States for our people.”

How did Ollie Jackson, a convicted killer barely thirty years old, acquire the resources and connections to pull this off so quickly? Only the long-dead denizens of the St. Louis underworld could answer that authoritatively, but the question itself may contain a partial answer.

At that time, relations between the all-white police force and much of the Black community were basically adversarial—especially in the vice district. The collapse of Reconstruction and the Panic of 1893 had driven waves of Southerners into St. Louis, parts of which now teemed with poor Black migrants. Police harassed them to no end, arresting anyone they pleased on charges of vagrancy. “Police brutality reached a point seldom equaled,” Arna Bontemps and Jack Conroy wrote in Anyplace But Here (1945), their study of Black migration to Midwestern cities.

One might think that racist application of police power would mean swift and severe punishment for Black murder suspects, but in cases involving Black victims, it tended to produce the opposite result. As Bontemps described it in his novel God Sends Sunday (1931), a Black man who killed another Black man in St. Louis was typically out of jail in time for the funeral: “In those days red-light murders were so commonplace they evoked but slight interest from the court authorities. Condemnations were rare. Almost anything passed for self-defense. Consequently the impression got about that the state did not wish to bother with crimes committed by Negroes against Negroes.” (Stack Lee’s conviction and long sentence were anomalies; he had killed the brother-in-law of Henry Bridgewater, a wealthy saloon owner, who had bankrolled a high-powered prosecution.) In short, Black neighborhoods were both overpoliced and, in matters of life and death, largely self-policing, and Black people tended to place more faith in street justice than in the justice system.

In such an environment, “badness” was its own currency, and Ollie Jackson had demonstrated his at an early age; provoking a deadly fight with the Carr brothers may have amounted to a career move for him. By 1901, the Carrs were familiar names in the crime pages. Eight years earlier, Dick Carr had shot a man in the shoulder over a poker game (also in Curtis’s saloon). In 1897, Babe Carr and a friend named Ben Mitchell had exchanged gunfire with a bartender in one of Bridgewater’s saloons; Mitchell had died. (One journalist would later allege, without basis, that they were attempting revenge for the prosecution of Stack Lee.) While in jail following the shootout, Babe had been caught receiving smuggled opium. He’d also been linked to a murder conspiracy in 1895 but not prosecuted. The Carr brothers were “bad men,” and some of that notoriety transferred to Ollie Jackson when he gunned them down. The newspaper coverage did its part to make Jackson sound formidable: “Judging from the number of bullet holes in the walls,” the Globe-Democrat announced, “Jackson must have used two revolvers, for there are more holes than chambers in a single weapon.” And of course there was a folk ballad making the rounds, depicting Jackson as the coolest of customers:

When the shootin’ was over,

Ollie looked big and stout.

He put his pistol in his pocket

And done the slow drag out.

When you lose your money, learn to lose.

By 1907, Jackson was “exalted ruler” of that Elks chapter, whose officers included such local luminaries as Charlton H. Tandy and George Vashon. The same year, a journalist noted that Jackson was “famed as the killer of two men.”

Jackson seemed to understand how to project success. A century before the term existed, he was a master of branding. Another Black newspaper, the Indianapolis Freeman, described him driving around St. Louis in a “$5,000 auto” that “carries the name of the ‘Modern Horseshoe.’” Years later, the ragtime pianist Charley Thompson recalled Jackson wearing a horseshoe-shaped diamond pin that “was big enough for a Shetland pony.”

Diamond jewelry was Jackson’s literal signature. When he sent an admiring letter to a department store clerk he’d met, he signed it “The Man With the Diamonds,” according to the Post-Dispatch. That information appeared in the newspaper because the clerk, Bertha Becker, was a white woman, and Jackson’s attention to her was scandalous. Becker’s boss notified the police, who instructed Becker to accept Jackson’s invitation to meet on an agreed-upon street corner. Two plainclothes officers lounged on the lawn of a nearby boarding house, and when “a flashy negro appeared” and began speaking to Becker, they leapt to their feet and arrested him. Jackson “wore diamonds on his fingers, in his shirt front and in his tie, worth about $2000, and carried a revolver,” the paper reported on its front page, under the headline “CAUSES ARREST OF BEDIAMONED [sic] NEGRO MASHER.” A couple of weeks later, a more subdued item on page four reported that Jackson’s criminal case had been dismissed for lack of laws against anything he’d done.

If turn-of-the-century St. Louis was “the geographic hub of the Negro sporting wheel,” as Bontemps described it, then Ollie Jackson, presiding over the Modern Horseshoe Club, was at the hub’s hub. In 1910 the Post-Dispatch called him “the king bee of the colored sporting world in St. Louis.” “Sporting” was a popular and flexible term, referring broadly to a life of indulgence and chance—gambling, drinking, carousing. In some contexts, its meaning narrowed: a “sporting house” was most likely a brothel; in the 1900 census, the vice district was full of women whose occupation was “sporting.” But the word also evoked competitive athletics, and probably derived from that association. “Sports” like Ollie Jackson loved watching and wagering on sports—especially horse racing, boxing, and baseball.

In late 1910, Jackson put his name and money behind the St. Louis Giants, a Black baseball team that an ambitious young manager named Charles Mills was transforming into a regional powerhouse. Nominally, Jackson was treasurer of the Giants organization; effectively, he was an owner, and some journalists even called him that. For the next couple of years Jackson was a conspicuous presence in the grandstands. After the team beat the mighty Leland Giants of Chicago in 1911, the Star alluded to Jackson’s reputation as the man with the winning touch: “With the score 3 to 1 against the team, Manager Charley Mills of the locals gave his seat near the press box to Ollie Jackson in the seventh, remarking ‘There’s Luck.’” When the Giants then rallied and won, Mills announced, “He’s fated. That’s where Ollie will sit after this.” Under Mills’s stewardship the Giants would evolve into the famed St. Louis Stars of the Negro National League, the team that produced Cool Papa Bell.

Jackson’s other great sports enthusiasm, perhaps inevitably, was the boxer Jack Johnson. In his taste for the trappings of wealth, his contempt for the color line, and his general fearlessness, Johnson was Jackson writ larger. The world heavyweight champion from 1908 to 1915, he wore huge diamonds, owned a fleet of expensive cars, loved to gamble, and was married three times to white women. Johnson was despised by white America, as much for his brazenness as for the ease with which he dispatched the numerous “Great White Hopes” sent to dethrone him. After winning the title from Tommy Burns, who had refused to shake his hand and had used racial slurs in the ring, Johnson said, “I could have put him away quicker, but I wanted to punish him.” His pummeling of former champion Jim Jeffries in the “Fight of the Century” triggered race riots throughout the country in 1910; many cities banned the screening of footage from the fight. Ollie Jackson was in the crowd for that bout, having traveled to Reno with a small group of prosperous Black St. Louisans to cheer on the champion. According to the Post-Dispatch, he had taken along “a big bank roll to wager on Johnson.”

By 1912, the two were friends. When Johnson came to St. Louis in March for a series of boxing exhibitions at the Standard Theater, Jackson hosted him in a suite of rooms above the Modern Horseshoe Club, and the pair spent their evenings feasting and gambling. A Denver newspaper reported that Johnson and “his friend, the Negro gambling king of St. Louis, Mr. Ollie Jackson” had won $1,300 between them in a single craps-shooting session. In the Globe-Democrat, Johnson discussed his plans to buy two large diamonds with the winnings. On March 10, the Post-Dispatch reported that the banquets held in Johnson’s honor at the Modern Horseshoe Club “were never equalled in colored society.”

Recommended

The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

A Picture of Stack Lee

Crossing Paths