Rebecca Foust was a James Hearst Poetry Prize Finalist in 2010.

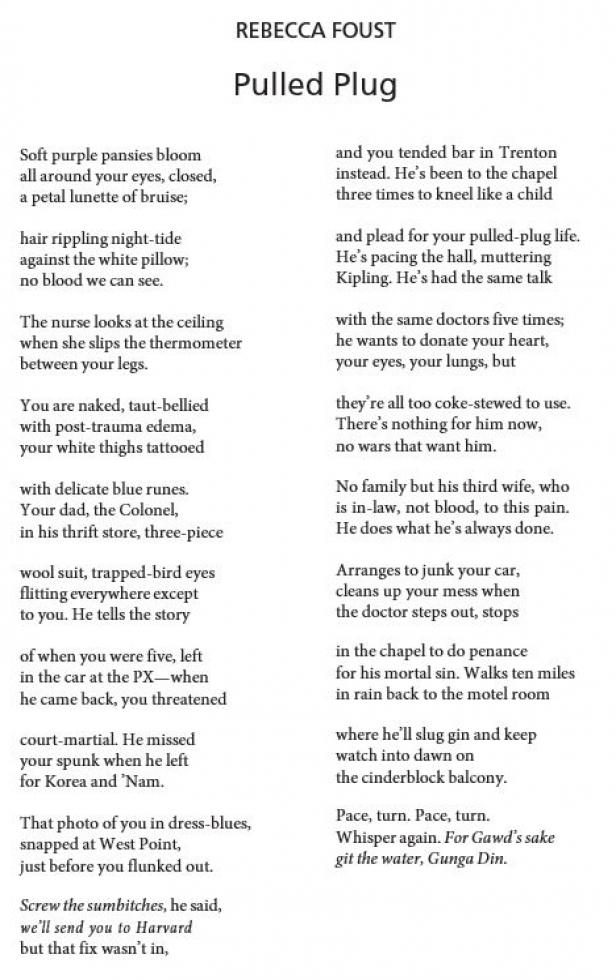

I wrote this poem sometime in 2008, not long after I first returned to writing after a 35-year hiatus, and so it was an early experiment in sustaining a longish poem (anything over a page was long for me then) and one made of short lines organized into tercets. The length was dictated by the length of the story I wanted to tell, for this is a narrative poem based, as many of my poems are, on an experience from life.

My mother’s second husband was a “Full Bird” army colonel who earned his promotions through battlefield commissions on multiple tours in Korea and Vietnam. The Colonel was fiercely proud of having come up this way and scornful of “college boys” who, when they got into real battle situations, did not, he said, know their ass from their weapon. An intelligent man, he escaped a poor, rural upbringing on a Pennsylvania farm by joining the army, and it was the army that paid for his college, graduate school, and the PhD in military history. After retirement, the Colonel lectured at war colleges and published two books in his field. He was an ambitious man, torn between disdain and admiration for higher institutions of earning, and a voracious reader. But all the reading I saw him do was through the narrow lens of his obsession with military tactics and history, and the only poet I ever heard him recite was Rudyard Kipling.

Before he married my mother, the Colonel fathered one child, DeeDee, a daughter who shared her father’s ambition and strong sense of grand destiny, but lacked the critical ingredient of his iron will. During her childhood, her father was mostly gone on military business and tours of duty. When he came home, he showered her with gifts and attention, and then went off again to drink with his men. The Colonel’s dream was to send DeeDee to West Point, and he pursued it even in the face of mounting evidence that she would not have the requisite test scores and grades.

Deedee did get admitted to West Point, presumably because her father had “pulled” strings, and she lasted less than a year before flunking out. Always an indifferent student, Deedee fell in with a bad crowd. We began to hear rumors about drugs—pot, cocaine, speed. All to which her father, rabidly anti-any-drug besides gin, turned a resolutely blind eye.

“Screw the sumbitches,” the Colonel said after Deedee got kicked out. “We’ll send her to Harvard, or Wharton,” and he began to write away for the applications. Deedee came back home and began spending time with another West Point dropout, a young man who, the time I met him was as close to being in uniform as you can get in civilian clothes: pressed black pants, white button down shirt, and spit-shined oxford shoes. The news of his death from a morphine overdose sent shock waves through the family, and it was shortly afterwards that Deedee got into the car her father had bought her and drove across the county to San Diego where, she announced, she intended to live.

For a few years, nobody talked much about Deedee. By then, I was living in San Francisco and so was the closest family member when the call came. “Deedee’s been in a car accident,” Mom told me. “Can you go? No one else can get there before tomorrow.” So I packed an overnight bag and caught a flight to a San Diego, then went straight to the hospital where this poem opens, to find Deedee was on life support. I sat with her until her mother arrived, followed a few hours later by the Colonel and my mother. We stayed for three days, shuttling back and forth between the hospital and the dank motel where the four of us shared one room. The poem is in that room, with its cinderblock deck overlooking the ocean, in the ICU, and in the hospital’s chapel where the Colonel, an avowed atheist since childhood, went every day to pray.

When we returned to the motel room it was to collapse on one of its two beds or fold-out couch to wait for the return of the Colonel, always the last to leave Deedee’s side. Just before making the trip from Pennsylvania he’d gone to the local thrift store to buy a suit for his book readings, and that was what he wore—all he wore—while in San Diego: a three-piece navy-with-pinstripe, tight across the chest and made of a wool much too heavy for a southern California climate. He began drinking on the plane and did not stop, so that the sweet smell of ferment oozing from his neck and palms made the doctors step back and roll their eyes when he pressed them with his urgent questions. On the last night, it began to rain, and the Colonel force-marched the four miles back from the hospital to the motel. When he opened the door, the room filled with the smell of sweat, mothballs, wet wool, and gin, and we asked him to go outside on the deck to air out. He stayed there all night, pacing back and forth, back and forth and reciting “Gunga Din.” The next morning he walked back to the hospital alone to sign the papers to disconnect his daughter’s life support.

Since the story inspiring this poem was already so heavy and fraught, I wanted a form that could hold it without collapsing under its own weight; that’s why I settled on short-line tercets, after experimenting first with longer lines and blockier stanza structures. The Colonel represented so many things I reflexively loathed: the military, war, alcoholism, misogyny, racism—all that. And yet there was something delicate and piercing in his fierce loyalty to and grief for his lost-in-the-woods daughter. As for Deedee, I sensed and feared her dark side and was put off by her coarseness and swaggering braggadocio. So I gave her a wide berth at family gatherings and did not look her up when she moved to CA.

In the ICU I saw a different Deedee, a more vulnerable, childlike creature, something feral and shy. She lay on the gurney, nude, covered only by a light blanket. Her face was unmarked except that her eyes, closed and hugely swollen, looked like ripe plums. I had plenty of time waiting in that room to notice her glossy black hair, and smooth, freckled skin. And, when the nurse came to take her vaginal temperature (brusquely it seemed to me) I saw the rest of Deedee’s young strong, and curiously unmarred body as well. Yes, except for those eyes she looked exactly like she was sleeping, and for the first time, I thought her beautiful, too.

Illustrator Clay Rodery lives in Houston, Texas just down the road from NASA Mission Control (which accounts for a lot). Clay is featured in issue 299.3, Summer 2014.