I don’t believe I can talk about why I wrote the poem “Orogeny” without first explaining why I set myself the task of writing about mountains. In some ways, it was a deliberate act. But in other ways, as it always is with poetry, it was about instinct and passion, about how the words felt as they stood to attention on the page. Poetry is often a grafting of vision, a way of handing our perspectives over to strangers in the hope they’ll see what we see—or at least be able to relate to it somehow.

I don’t believe I can talk about why I wrote the poem “Orogeny” without first explaining why I set myself the task of writing about mountains. In some ways, it was a deliberate act. But in other ways, as it always is with poetry, it was about instinct and passion, about how the words felt as they stood to attention on the page. Poetry is often a grafting of vision, a way of handing our perspectives over to strangers in the hope they’ll see what we see—or at least be able to relate to it somehow.

Some of us, and I include myself here, are primarily portrait poets. We write mainly using the first-person/confessional point of view. We’re concerned with the lives of ourselves (self-portraiture) and with the lives of others. We’re fascinated by the human condition. Our poems are sometimes catalyzed by the literal and the “real,” though the real can include dream states and other surrealistic experiences; at other times, we’re inspired by ideas and contemplation. Either way, we want to discover something that sheds light on what it means to be human, and we’re prepared to wrestle with our subjects on the page to make them matter to ourselves and others.

Then there are poets who seem—to me at least—to be inspired primarily by the natural world. I think of them as landscape poets. They inhabit the world of the environment. Not simply the world of nature but also urban landscapes and sometimes historical ones. Their point of view can be sweepingly panoramic, or they can be compelled to utterance by the shocking, glorious intimacies that occur inside a particular place and time. In these poems, setting becomes as important as character does in the portrait poems described above. Landscape poets are masters of careful observation, lyricism, and accuracy. Dramatic situations often exist in their writing. Something is seen and noted. The world external to the poet is frequently foregrounded, though a fusion of internal and external landscapes is common too.

In my Form and Theory classes, we talk about other thematic/subject preoccupations too, as well as the wide variety of approaches used by poets I call textual prophets and others who I like to think of as sound wizards. For these poets, language and/or form and/or cadence is as urgent a question as subject. (In fact, most of us write inside all four of these different modes at one time or another, particularly before we’ve attached ourselves to our own “voices.”) But when I wrote “Orogeny,” I was thinking of how I needed to inhabit landscape again.

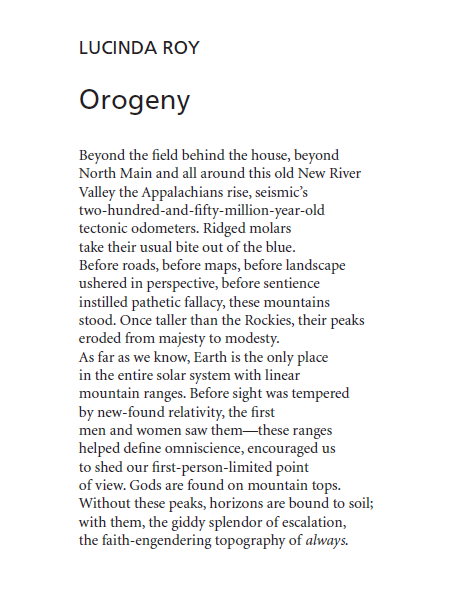

Photo by Richard Mallory Allnutt

Photo by Richard Mallory AllnuttAt the back of our house there’s a lovely view of the mountains. We live in the heart of Southwest Virginia in Blacksburg, and I wanted to capture the mountain ridges in much the same way as I try to capture subjects when I paint with oils, using color and shade and contour. That’s what logic tells me was going on, but it’s only partially true. In fact, when I wrote “Orogeny” I did so because I knew that my comfort zone wasn’t the natural world. I knew that unpopulated landscapes weren’t something I wrote about as often as I wrote about people. I wanted to challenge myself. Living amongst these mountains has reshaped me. Though “Orogeny” began as a poem about mountain formation, it became a poem that explores how setting shapes point of view—how we know who we are because of the environments in which we live.

I decided to write it in irregular blank verse (mostly unrhymed iambic pentameter, with occasional internal slant/half rhyme and copious metrical substitutions) because there is something about that kind of heart-beat rhythm that allows you to propel a poem forward, to give it a similar momentum to the kind we create in our novels and short stories when we employ pacing and plot. It also felt to me that blank verse was a tonal match for the poem, invoking the weight of history and legacy. I like the term “orogeny.” It’s related to terms like “progeny” and so conjures up both offspring and posterity. It also seemed to me as I looked at these mountains and thought about the others along the Blue Ridge that it was their age that spoke to me the most. Their millions of years far outweighed ours. I thought about how awestruck ancient humans would have been when they climbed to the peaks of mountains centuries before skyscrapers or planes. Ironically, I wound up thinking about the limitations of the first-person point of view, which seems to me to be one of the enduring thematic concerns of landscape poetry—the idea that what is seen and understood is always only a fraction of what is there.

When I read it, the poem seems to be about wonder. It seems to be reminding me that perspective and even sentience must sometimes make room for new ways of being in the world. Perhaps it’s no surprise, therefore, that the poem seems more like a prayer, a supplication to some great “Others” that

Lucinda Roy: Lucinda Roy is an Alumni Distinguished Professor in English at Virginia Tech, where she teaches poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction. Her books include the poetry collections Wailing the Dead to Sleep and The Humming Birds; the novels Lady Moses and The Hotel Alleluia; and No Right to Remain Silent: What We’ve Learned from the Tragedy at Virginia Tech, a memoir-critique. Her poems have appeared recently or are forthcoming in American Poetry Review, Blackbird, Callaloo, Crab Orchard Review, Measure, Poet Lore, Prairie Schooner, River Styx, and many others.

Illustration (top) by; Clay Rodery. Clay Rodery is a painter and illustrator who lives and works in New York City.