I remember when Allen Ginsberg sold his old letters and notes and drafts to a library archive for a million dollars, or something like that. A lot of people complained that he had “sold out.” Many of my older literary pals sold their materials for big bucks as well: Norman Mailer, James Michener, Joseph Campbell, and John Updike. I assume American Nobelists Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck did the same thing. In the old days, that’s what happened. After a lifetime of writing literature and corresponding with other famous folks, writers would sell their boxes full of musty letters and doodles and scribbles to libraries for posterity. The idea was that future scholars could study the materials and write articles and books with titles like The Collected Letters of So-and-So.

I enjoyed the epistolary tradition of exchanging letters with Norman Mailer, Gary Snyder, Denise Levertov, Seamus Heaney, and dozens of other literary friends, many now gone from our midst. Nowadays, everyone uses email. What a shame. There was something special about a handwritten letter with a handwritten address on the envelope. Some writers like Abenaki writer Joseph Bruchac and Ted Hughes even drew little pictures accompanying their signature. You knew that writer had touched it, had licked the gummed seal and the postage stamp. There was a genuine human connection that is lost in an email.

I wonder about the future of archives. Nowadays, we open our work-in-progress on our laptop at a coffee house, tinker with it for a while, click “Save,” and when the prompt asks if we want to save the changes, we click yes, thereby erasing the history of that work, be it poem, short story, or novel. A work may have had a hundred drafts before being published, but we will never know a single one of those earlier versions. Certainly the modern process is efficient and saves trees, but what literary artifacts will writers leave behind for those interested in understanding how a piece of literature came to be, what it might have been at one time or another? Did an early version of a masterpiece begin with a different first chapter or have an alternative ending? Was a beloved protagonist originally cast in a less flattering light? And what about marginalia, those wonderful, insightful, and sometimes fanciful scribbles and doodles in the margins that tell us something about the writer and his or her process?

What is the price of progress?

Every writer should have a friend or friends who act as sounding boards for ideas and who offer useful, brutally honest criticism. No writer benefits from “Yes Men” who smile and meekly reply, “I like it.” How did the critical advice of other writers mold the finished work, as Ezra Pound helped to mold T. S. Eliot’s poetic masterwork The Waste Land?

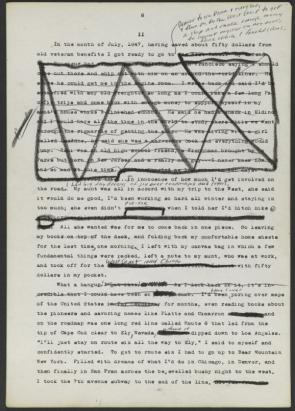

What parts of his novel did Jack Kerouac excise from the typescript of On the Road? As a writer, there’s something comforting in the knowledge that even the greatest writers struggled with their work, just as we do, that great writing is the product of hard work and persistence, and that things don’t just fall “trippingly from the stars” or some bright-eyed muse.

And what other artifacts of the writer’s craft will be displayed in future museums? At the Writer’s Museum in Dublin, patrons can see objects from the writing life of James Joyce, William Butler Yeats, Jonathan Swift, Oscar Wilde, and Samuel Beckett. Today, at Goldeneye, Ian Fleming’s cottage in Jamaica, viewers can stand a foot away from the gold-plated typewriter upon which Fleming typed many of his James Bond spy novels. In Louisville, Kentucky, admirers can see the typewriter from Thomas Merton’s hermitage upon which he typed countless letters to folks like Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Dalai Lama, and typed many of his books on religion, social rights, and peace. Seeing such objects up close and imagining the tick-tick-tack of fingers working the keys evokes a kind of intimacy, an unbroken chain of writers, connecting ourselves to that great and illustrious tradition. Will museums in the future display thumbdrives, laptops, and iPads?

John Smelcer is the author of more than fifty books, including his award-winning novel The Trap, listed as among the 101 greatest novels to teach the English language. His tenth collection of poetry, Indian Giver, was just released this month. For almost a quarter century he has served as poetry editor at Rosebud. Learn more at www.johnsmelcer.com

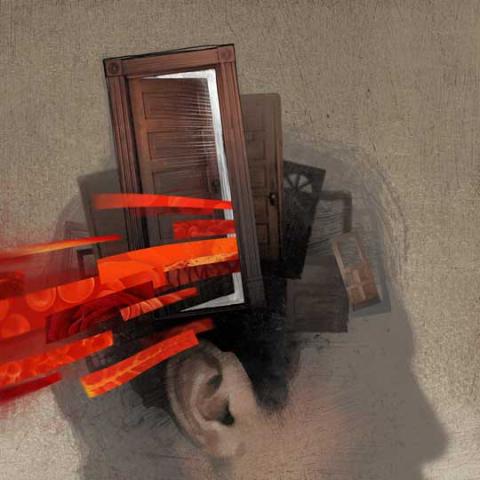

Illustration by Matt Manley. Matt has been working as a freelance illustrator for over twenty years. His illustration is primarily figurative and symbolic with surrealist leanings, and past client work includes editorial, corporate, medical, book, and higher education. Though in the end his work is technically digital collage, the process integrates both traditional and digital media. Collage elements are original oil paintings and drawings, with occasional scanned found objects and photos added to the mix, all united in Photoshop .